A few years ago, I wrote a short story for an anthology on the theme of Escape, published by the Northwest Independent Writers Association (NIWA). My story was titled “View from the Bottom of a Lake.” The genre of that story is not fantasy, although it is a dream, a memory of a time gone by.

One of the requirements for that anthology was that all stories must be set in the Pacific Northwest. I set mine in an environment I knew well, the shore of the lake that dominated my early years. With my setting established, I went online and looked up every synonym for the second requirement, which was the theme: “escape.”

One of the requirements for that anthology was that all stories must be set in the Pacific Northwest. I set mine in an environment I knew well, the shore of the lake that dominated my early years. With my setting established, I went online and looked up every synonym for the second requirement, which was the theme: “escape.”

Then, after I had all the synonyms, I looked for the antonyms, the opposites.

Capture. Imprisonment. Confront.

Once I had a full understanding of all the many nuances of the theme, I asked myself how I could write a story set in an environment I knew and loved. My solution was to set it in the late 1950s. Anything that is history may as well be fantasy because the victors write the history books.

Once I had a full understanding of all the many nuances of the theme, I asked myself how I could write a story set in an environment I knew and loved. My solution was to set it in the late 1950s. Anything that is history may as well be fantasy because the victors write the history books.

Then, I began plotting.

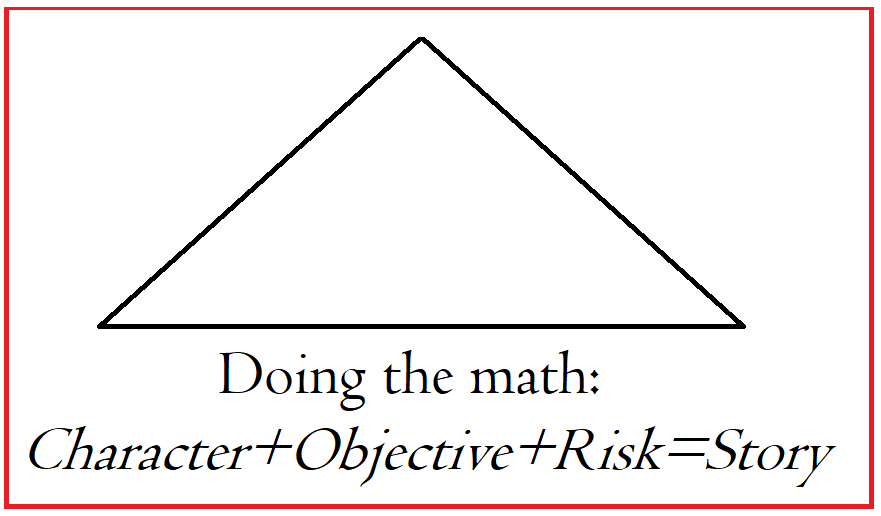

The main theme of escape had to form the backbone of the plot, that was a given. I asked what my character needed most in her effort to escape. My gut answer was courage.

The first subtheme, the one that formed my main character, was courage. She is underage, fearful of her narcissistic mother, and armed with the knowledge of what she must do to escape.

Every day, she escapes her mother’s disdain by swimming in the lake and staying underwater as long as she can. In those brief moments of freedom, she plans for her long-term escape, determined that once she goes away to college, she won’t return. Her grandmother, who is also a prisoner in that household, is determined to help her escape by paying for her education.

The story loops around my protagonist’s fractured family and their twisted relationship with the nearest neighbors.

The story loops around my protagonist’s fractured family and their twisted relationship with the nearest neighbors.

The second subtheme is hypocrisy. This is a theme of morality, of “do as I say, not as I do.” The parents live out their failed dreams through their children. The girl is forced to take ballet lessons that she despises, and the boy must play football. The girl’s mother is a former ballerina who got pregnant and had to get married, ending her career before it got started. The boy’s father’s glory days were his years as a small-town jock, before WWII changed everything.

In their social world, appearances are everything. And everything is colored by her mother and his father and what everyone knows but cannot speak of.

The final subthemes of that story are hope and perseverance, and in many ways, those themes are the most important.

For the girl, romance with the boy next door is still only a possibility, but the seeds are there through their lifelong friendship. Their plans will come to fruition if only they can survive their senior year and graduate with high grades. All they have to do is endure the pressure cookers of their homes for one more year, and they will achieve their post-high school dreams.

Thus, contrasts drive that short story, and strong themes enabled me to write that tale in three days. The brilliant Lee French was the editor for Escape, and her input was invaluable. View from the Bottom of a Lake is (in my opinion) my best work. Ever.

So, what can I take from that experience to breathe life into my current work-in-progress?

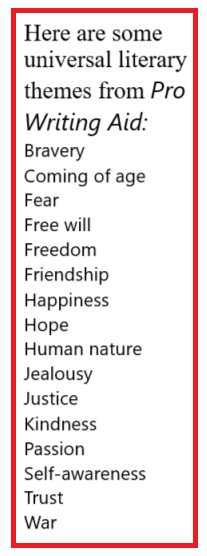

First, I need to identify the overall theme for this half of the story. A comprehensive list of literary themes can be found here: A Huge List of Common Themes – Literary Devices.

The main theme, as I see it now, is two-fold. The theme of religion is explored in the war of the gods, and how a lust for power corrupts one of them.

The mortals are the playing pieces in their great game. For the people who must live their lives in the shadow of this war, the more immediate theme of change in the face of tradition underpins the plot. It is explored through the protagonist’s quest to save his people despite their stubborn clinging to xenophobic traditions.

The mortals are the playing pieces in their great game. For the people who must live their lives in the shadow of this war, the more immediate theme of change in the face of tradition underpins the plot. It is explored through the protagonist’s quest to save his people despite their stubborn clinging to xenophobic traditions.

- My protagonists do have some allies, but they must unite the tribes and convince them of the danger presented by the antagonist.

- My antagonist knows how the more traditional tribes fear change and ruthlessly stokes that fire.

The enemy presents himself as the man who will keep to the old ways, even though it means abandoning the Goddess Aeos and switching their loyalty to the Bull God. He lies to them about that minor detail, but justifies it as a good lie, a necessary lie.

So, a third subtheme that runs through the second half of this story is morality. The antagonist can manipulate things and people to achieve his goals. He doesn’t see this as immoral. While the villain is spreading disinformation, the protagonist must try to convey the truth to people who don’t want to hear it. He must convey the facts in such a way that even the staunch traditionalists will see how the antagonist manipulates them.

So, a third subtheme that runs through the second half of this story is morality. The antagonist can manipulate things and people to achieve his goals. He doesn’t see this as immoral. While the villain is spreading disinformation, the protagonist must try to convey the truth to people who don’t want to hear it. He must convey the facts in such a way that even the staunch traditionalists will see how the antagonist manipulates them.

In real life, everyone is a mass of contradictions we aren’t really aware of. Sometimes, it helps if I use polarities (opposites, contrasts) to flesh out a character. They help me flesh out the protagonist and also the antagonist.

- courage – cowardice

- manipulative – honorable

- truth – misinformation

Now, while I fill in the plot, I am also noting ideas that will support the themes as they come to me. Good use of contrasts will (hopefully) illuminate my characters’ motives and intentions as they work toward the final goal.

Over the next year, I will expand on all these themes and bring this epic to the desired conclusion.

I talk a lot about craft, and yes, it is important. But I believe the most important aspect of the writing process is to have passion for the characters and their story. Writing always flows well when I am emotionally involved.

How is your writing going? Are you able to stay emotionally involved with the characters and their lives?

Lesser dramas might only touch us on a peripheral level, yet they can affect our sense of security and challenge our values.

Lesser dramas might only touch us on a peripheral level, yet they can affect our sense of security and challenge our values.

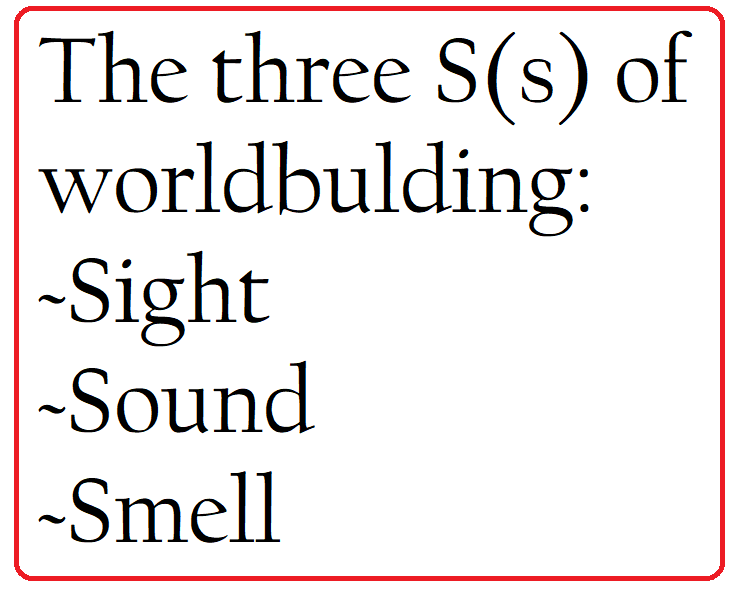

The camera zooms out and now we see the idyllic serenity of a clear sunny morning on Spirit Lake and Harry doing his morning chores.

The camera zooms out and now we see the idyllic serenity of a clear sunny morning on Spirit Lake and Harry doing his morning chores. We writers must make our words count. We must show our characters in their comfort zone in the moments leading up to the disaster. Not too much of a lead in, but just enough to show what will soon be lost.

We writers must make our words count. We must show our characters in their comfort zone in the moments leading up to the disaster. Not too much of a lead in, but just enough to show what will soon be lost. I aspire to write like my heroes, authors who create characters who come alive. While I’m in that world, I see the people and their stories as sharply as the author intends.

I aspire to write like my heroes, authors who create characters who come alive. While I’m in that world, I see the people and their stories as sharply as the author intends. Polarity gives the important elements strength. It provides texture but often goes unnoticed while it influences a reader’s perception.

Polarity gives the important elements strength. It provides texture but often goes unnoticed while it influences a reader’s perception. I use the

I use the

Tad Williams’s

Tad Williams’s No matter where we live, San Francisco, Seattle, or Middle Earth, these fundamental human experiences are personal to every reader. We have each experienced pain and loss, joy and love.

No matter where we live, San Francisco, Seattle, or Middle Earth, these fundamental human experiences are personal to every reader. We have each experienced pain and loss, joy and love. Plot, in my opinion, is driven by the highs and lows. You don’t need to pay for books you won’t like. Go to the library or to the secondhand bookstore and see what they have from the NYT bestseller list that you would be willing to examine.

Plot, in my opinion, is driven by the highs and lows. You don’t need to pay for books you won’t like. Go to the library or to the secondhand bookstore and see what they have from the NYT bestseller list that you would be willing to examine.

One of my favorite authors is Tad Williams, who wrote the watershed series,

One of my favorite authors is Tad Williams, who wrote the watershed series,