The first Monday in September is Labor Day in the US, a holiday marking the end of summer. This is the day we honor those whose labor keeps this country running. Over the years, I have worked in a wide variety of menial jobs. All were low-paying and didn’t garner much respect from those in higher-status positions or from management. But I liked my work and never did less than my best.

Childcare was always an issue. Sometimes, during the Carter years, I qualified for government-subsidized childcare vouchers, which was the only reason I could work such low-paying entry-level jobs. Later, my uncle cared for my youngest daughter after school until she was about ten. Because I had that childcare subsidy when my youngest was not yet of school age, I was able to support my family relatively well.

Childcare was always an issue. Sometimes, during the Carter years, I qualified for government-subsidized childcare vouchers, which was the only reason I could work such low-paying entry-level jobs. Later, my uncle cared for my youngest daughter after school until she was about ten. Because I had that childcare subsidy when my youngest was not yet of school age, I was able to support my family relatively well.

They should bring that childcare subsidy back. Once they reached ten years of age, my kids were latchkey kids, which wasn’t uncommon in those days.

In the 1970s-80s, I worked as a bookkeeper, an automobile detailer, a field hand for a (now defunct) multi-national Christmas tree company, a photo lab tech, a waitress in a bakery, and worked in a delicatessen.

During those years, my favorite job was as a field hand for the J. Hofert Company. They grew Christmas trees of all varieties, and I absolutely loved the work. It was outdoors, paid $3.25 an hour, and was seasonal, so I usually had a month off three times a year. I was able to work all the overtime hours I wanted during certain seasons, as field hands were as hard to get then as they are now.

Coins, Microsoft content creators

Sometimes, especially during the Reagan years and up to 1996, wages were low, and jobs were scarce. I held two, and sometimes three, part-time jobs to keep the roof over my children’s heads and food on their table. Trickledown economics never quite trickled down to my town.

In the late 1980s and through the 1990s, I worked as a hotel maid, a photographer’s assistant and darkroom technician, and as a bookkeeper/office manager for a charter bus company.

Life became easier in the 1990s. As a bookkeeper/office manager, I earned $7.50 an hour (two dollars over minimum at the time) and worked less than 30 hours a week with no benefits whatsoever. I drove for an hour each way, morning and afternoon, for that job.

As a hotel housekeeper in a union shop, on the days I wasn’t a bookkeeper, I made $8.50 (three dollars over minimum) and worked about 20 hours a week, giving me enough from the two jobs to live on and provide well for my children. I was still legally married to my 3rd husband, but he was seldom in the picture. The marriage was a shield between me and my well-meaning matchmaker friends.

I was divorced from hubby number three in 1997, and oddly enough, things became much easier financially. I was able to get by with only one job, even while raising my last teenager. (See? Everyone has a soap opera life, even famously unknown authors.)

I was divorced from hubby number three in 1997, and oddly enough, things became much easier financially. I was able to get by with only one job, even while raising my last teenager. (See? Everyone has a soap opera life, even famously unknown authors.)

For all the years I was married to my 3rd husband, no matter what other job I had, I kept my weekend job at the hotel. I kept it because I always had that to fall back on. I had risen in seniority and could work full-time whenever the other jobs went away.

My hotel was affiliated with a good union. We who did the dirty work earned far more than maids, housemen, and laundresses at other hotels. We also had benefits such as paid sick leave, up to two weeks a year of paid vacations, good health insurance, and a 401k, to which our employer matched our contributions.

In any hotel, housekeepers are considered the lowest of the low by the other employees. No one is of less social value than the person who cleans up after other people. Without the union, we would have had nothing more than the bare minimum wage and a cartload of insincere condescension from management.

Not every union is good or reasonable. But while I don’t agree with everything every union does and stands for, I am grateful that a good, reasonable organization protected my family and me during those years of struggle.

After 2000, I worked as a temp employee at Verisign, a tax preparer for H&R Block, and did data entry for LPB Energy Management. By 2010, I was thoroughly sick of corporate America and had returned to bookkeeping, this time for a local landscape company.

That job was a joy.

In my younger days, I worked every weekend and every holiday, and yes, it was not easy, but it was what it was. My kids were good and supportive, and they knew I was doing my best for them.

Every worker deserves an employer who treats them with respect and offers a fair wage in return for their labor.

The world is a different place now in many ways. Even so, someone must do the dirty jobs, the work that no one else wants. I have nothing but respect for those who work long, hard hours in all areas of the service industry, struggling to support their families.

My experiences working in the lower echelons of the labor force inform my writing. Look around you and see the people who make your life easier by being there every day doing their jobs.

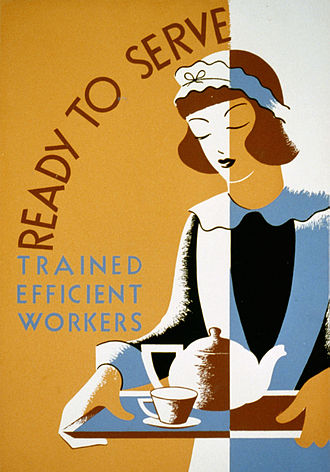

Stylized drawing of a maid on a Works Progress Administration poster via Wikipedia

Every waitress/waiter, housekeeper, laundry worker, caregiver, bartender, welder, mechanic—everyone in the service industry is a living, caring human being with hopes, ambitions, triumphs, and tragedies. Every one of them has a story and a reason to be where they are, doing the task they have been given.

Say a little thank you to all those who endure verbal abuse when a customer is stressed out and “doesn’t have time to wait” or is upset by things they have no control over and vent their anxiety at someone who can’t (or won’t) fight back.

Give a little thanks to those whose labor enables you to live a little easier.