Beta Reading is the first look at a manuscript by someone other than the author. It’s best when the reader is (1) a person who reads for pleasure and can gently express what they think about a story or novel and (2) a person who enjoys the genre of that particular story.

I am fortunate to have excellent friends willing to do this for me. Their suggestions are thoughtful and spot-on.

I am fortunate to have excellent friends willing to do this for me. Their suggestions are thoughtful and spot-on.

This first reading by an unbiased eye is meant to give the author a view of their story’s overall strengths and weaknesses. This phase should be done before you submit the manuscript to an editor.

In my work, the suggestions offered by the beta reader (first reader) guide and speed up the revision process. My editor can focus on doing her job without being distracted by significant issues that should have been caught early on.

In my work, the suggestions offered by the beta reader (first reader) guide and speed up the revision process. My editor can focus on doing her job without being distracted by significant issues that should have been caught early on.

If you agree to read a raw manuscript for another author, remember that it has NOT been edited. Beta Reading is not editing, and the reader should not make comments that are editorial in nature. Those kinds of nit-picky comments are not helpful at this early stage because the larger issues must be addressed before the fine-tuning can begin.

This phase of the process should be done before you submit the manuscript to an editor, ensuring those areas of concern will be straightened out first.

This manuscript is the child of the author’s soul. Be sure to make positive comments along the way, and never be chastising or accusatory. Always phrase your suggestions in a non-threatening manner.

What significant issues must be addressed in the first stage of the revision process? If you are asked to beta read for a fellow author, ask yourself these questions about the overall manuscript:

How does it open? Did the opening hook you? As you read, is there an arc to each scene that keeps you turning the page? Make notes of any places that are confusing.

Setting: Does the setting feel real? Did the author create a sense of time, mood, and atmosphere? Is world-building an essential part of the story?

Characters: Is the point of view character (protagonist) clear? Did you understand what they were feeling? Were they likable? Did you identify with and care about them? Were there various character types, or did they all seem the same? Were their emotions and motivations clear and relatable?

Characters: Is the point of view character (protagonist) clear? Did you understand what they were feeling? Were they likable? Did you identify with and care about them? Were there various character types, or did they all seem the same? Were their emotions and motivations clear and relatable?

Dialogue: Did the dialogue and internal narratives advance the plot? Did they illuminate the tension, conflict, and suspense? Were the conversations and thoughts distinct to each character, or did they all sound alike?

Pacing: How did the momentum feel? Where did the plot bog down and get boring? Do the characters face a struggle worth writing about, and if so, did the pacing keep you engaged?

Does the ending surprise and satisfy you? What do you think might happen next?

What about grammar and mechanics? At this point, you can comment on whether or not the author has a basic understanding of grammar and industry practices that suit their genre.

Be gentle! Phrase your suggestions with kindness. If the author’s work shows they don’t understand industry grammar and basic punctuation standards, suggest they get a style guide such as the Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation. Or, if you feel up to it, offer to help them learn a few basics.

I know how difficult sharing your just-completed first draft with anyone is. For that reason, being the first reader of another author’s work is a privilege I don’t take lightly.

So, we now know that beta reading is not editing. We now know the first reader makes general suggestions to help the author achieve their goals when revising.

Editing is a process unto itself and is the final stage of making revisions. The editor goes over the manuscript line-by-line, pointing out areas that need attention: awkward phrasings, grammatical errors, missing quotation marks—many things that make the manuscript unreadable. Sometimes, major structural issues will need to be addressed. Straightening out all the kinks may take more than one trip through a manuscript.

Editing is a process unto itself and is the final stage of making revisions. The editor goes over the manuscript line-by-line, pointing out areas that need attention: awkward phrasings, grammatical errors, missing quotation marks—many things that make the manuscript unreadable. Sometimes, major structural issues will need to be addressed. Straightening out all the kinks may take more than one trip through a manuscript.

There are different kinds of editing, as the various branches of literature have requirements that are unique to them:

In academic writing, editing involves looking at each sentence carefully and ensuring it’s well-designed and serves its purpose. In scholastic editing, every grammatical error must be resolved, making words and sentences more straightforward, precise, and effective. Weak phrasings are strengthened, nonessential information is weeded out, and important points are clarified.

In novel writing, editing is a stage in which a writer and editor work together to improve a draft by ensuring usages are consistent. The editor does not try to change an author’s voice but does point out errors. If an author’s style breaks convention, the editor ensures it is flouted consistently from page one to the end of the manuscript. At the same time, strict attention is paid to the overall story arc.

An editor is not the author. They can only suggest remedies, but ultimately all changes must be approved and implemented by the author.

An editor is not the author. They can only suggest remedies, but ultimately all changes must be approved and implemented by the author.

Be careful when you ask a person to read your manuscript. Some people cannot see the flowers among the weeds and will be blunt and dismissive in their criticism. That is not what you want at that early point. You want an idea of whether you are on the right track with your plot and characters and if your basic storyline resonates with the reader.

Do yourself a favor. Try to find a reader who understands what you are asking of them. You want someone who enjoys beta reading.

When you have made the revisions your first reader suggested and feel your book is ready, hire a local, well-recommended editor. You need someone you can work with, a person who wants to help you make your manuscript ready for publication.

You might wonder why you need an editor when you’ve already spent months fine-tuning it. The fact is, no matter how many times we go over our work, our eyes will skip over some things. We are too familiar with our work and see it as it should be, not as it is.

A reader won’t be familiar with it and will notice what we have overlooked.

A reader won’t be familiar with it and will notice what we have overlooked.

In my own work, a passage sometimes seems flawed. But I can’t identify what is wrong with it, and my eye wants to skip it. But another person will see the flaw, and they will show me what is wrong there.

That tendency to see our writing ‘as it should be and not how it is’ is why we need other eyes on our work. Our eyes might trick us, but another reader will see it clearly.

Next week, we’ll talk about the final draft and the process I use to make my manuscript ready for my editor.

When observed by others, a person who is daydreaming appears lazy. Mind-wandering has no obvious purpose, but it is critical for creativity. Every groundbreaking discovery in science, every great invention we enjoy today—all were inspired by ideas that came to a person while thinking about something else or when they were mind-wandering.

When observed by others, a person who is daydreaming appears lazy. Mind-wandering has no obvious purpose, but it is critical for creativity. Every groundbreaking discovery in science, every great invention we enjoy today—all were inspired by ideas that came to a person while thinking about something else or when they were mind-wandering. My oldest daughter, looking at our dinner, a casserole of beans with cornbread baked on top like a cobbler: “What the heck is that?”

My oldest daughter, looking at our dinner, a casserole of beans with cornbread baked on top like a cobbler: “What the heck is that?” Perception is in the eye of the beholder. Observation and thought are seeds that inspire extrapolation, leading the viewer to come away with new ideas. When I see the story captured in a single scene by an artist, my mind always surmises more than the painting shows. I see the picture as depicting the middle of the story and imagine what came before and what happened next. Unintentionally, I put a personal spin on my interpretation, and ideas are born. I don’t mean to, but everyone does.

Perception is in the eye of the beholder. Observation and thought are seeds that inspire extrapolation, leading the viewer to come away with new ideas. When I see the story captured in a single scene by an artist, my mind always surmises more than the painting shows. I see the picture as depicting the middle of the story and imagine what came before and what happened next. Unintentionally, I put a personal spin on my interpretation, and ideas are born. I don’t mean to, but everyone does. This means that daydreaming is actually good for you. It boosts the brain, making our thought process more effective. Letting the mind wander allows a kind of ‘default neural network’ to engage when our brain is at wakeful rest, as in meditation, rather than actively focusing on the outside world. When we daydream, our brains can process tasks more effectively.

This means that daydreaming is actually good for you. It boosts the brain, making our thought process more effective. Letting the mind wander allows a kind of ‘default neural network’ to engage when our brain is at wakeful rest, as in meditation, rather than actively focusing on the outside world. When we daydream, our brains can process tasks more effectively. You could be watching the birds, as my husband and I often do. Or maybe you’re perusing the display in a local art gallery or listening to music. I love all genres of music, but for writing I often find inspiration in powerhouse classical pieces such as Orff’s cantata,

You could be watching the birds, as my husband and I often do. Or maybe you’re perusing the display in a local art gallery or listening to music. I love all genres of music, but for writing I often find inspiration in powerhouse classical pieces such as Orff’s cantata,  Today, however, I plan a long walk along the beach.

Today, however, I plan a long walk along the beach. I have no trouble selling my friends’ books – I’ve read them all and love them, and love selling them. Maybe I can sell their books because I’m not emotionally invested in their creation, but I am invested as a reader.

I have no trouble selling my friends’ books – I’ve read them all and love them, and love selling them. Maybe I can sell their books because I’m not emotionally invested in their creation, but I am invested as a reader. Next week on this blog we will talk about the creative process and the importance of mind-wandering. We’ll also talk about why it is important to beta read for your fellow writers, and how to be a good reader, one who gives positive feedback and offers constructive suggestions.

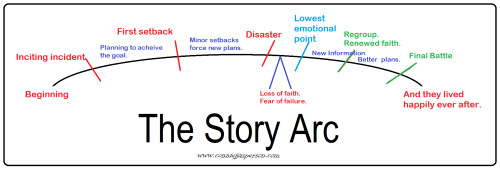

Next week on this blog we will talk about the creative process and the importance of mind-wandering. We’ll also talk about why it is important to beta read for your fellow writers, and how to be a good reader, one who gives positive feedback and offers constructive suggestions. Some novels are character-driven, others are event-driven, but all follow an arc. I’m a poet, and while I read in every genre, I seek out literary fantasy, novels with a character-driven plot. These are works by authors like

Some novels are character-driven, others are event-driven, but all follow an arc. I’m a poet, and while I read in every genre, I seek out literary fantasy, novels with a character-driven plot. These are works by authors like  And the prose … words with impact, words combined with other words, set down in such a way that I feel silly even thinking I can write such works. Thankfully, my editor weeds out pretentious hyperbole and slaps me back to reality.

And the prose … words with impact, words combined with other words, set down in such a way that I feel silly even thinking I can write such works. Thankfully, my editor weeds out pretentious hyperbole and slaps me back to reality. This part of the novel is often difficult for me to get right. The protagonist must be put through a personal crisis. Their inner world must be shaken to the foundations.

This part of the novel is often difficult for me to get right. The protagonist must be put through a personal crisis. Their inner world must be shaken to the foundations. This emotional low point is necessary for our characters’ personal arcs. It is the place where they are forced to face their weaknesses and rebuild themselves. They must discover they are stronger than they ever knew.

This emotional low point is necessary for our characters’ personal arcs. It is the place where they are forced to face their weaknesses and rebuild themselves. They must discover they are stronger than they ever knew. And what of my female protagonist? Where does her story begin?

And what of my female protagonist? Where does her story begin? I must introduce a story-worthy problem in those pages, a test propelling the protagonist to the middle of the book. The opening paragraphs are vital. They are the hook, the introduction to my voice, and must offer a reason for the reader to continue past the first page.

I must introduce a story-worthy problem in those pages, a test propelling the protagonist to the middle of the book. The opening paragraphs are vital. They are the hook, the introduction to my voice, and must offer a reason for the reader to continue past the first page. My favorite books open with a minor conflict, evolving to a series of more significant problems, working up to the first pinch point, where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

My favorite books open with a minor conflict, evolving to a series of more significant problems, working up to the first pinch point, where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

In literary terms, this uneven distribution of knowledge is called asymmetric information. We see this all the time in the corporate world.

In literary terms, this uneven distribution of knowledge is called asymmetric information. We see this all the time in the corporate world. Jared is hilarious, charming, naïve, a bit cocky, and completely unaware that he’s an arrogant jackass. He is a young man who is exceptionally good at everything and is happy to tell you about it. Jared has no clue that his boasting holds him back, as no one wants to work with him.

Jared is hilarious, charming, naïve, a bit cocky, and completely unaware that he’s an arrogant jackass. He is a young man who is exceptionally good at everything and is happy to tell you about it. Jared has no clue that his boasting holds him back, as no one wants to work with him. When I started writing this story, I had the core conflict: Jared’s misguided desire to be important. I had the surface quest: rescuing the kidnapped kid. I had the true quest: Jared learning to laugh at himself and developing a little humility.

When I started writing this story, I had the core conflict: Jared’s misguided desire to be important. I had the surface quest: rescuing the kidnapped kid. I had the true quest: Jared learning to laugh at himself and developing a little humility. Calendar time is a layer of world-building. It sets the story in a particular era and shows the passage of time.

Calendar time is a layer of world-building. It sets the story in a particular era and shows the passage of time. Consider the following sentences: “I eat,” “I am eating,” “I have eaten,” and “I have been eating.”

Consider the following sentences: “I eat,” “I am eating,” “I have eaten,” and “I have been eating.” Every story is unique; some work best in the past tense, while others must be set in the present.

Every story is unique; some work best in the past tense, while others must be set in the present. If I were writing a story starring me as the main character, I would open it in the year 2005 with a couple of empty-nesters buying a house in a bedroom community twenty miles south of Olympia.

If I were writing a story starring me as the main character, I would open it in the year 2005 with a couple of empty-nesters buying a house in a bedroom community twenty miles south of Olympia. The city center is isolated, twelve miles from the freeway and twenty miles away from every other town in the south county. If a fictional story were set in this town, it would feature the same political and religious schisms that divide the rest of our country. There are other tensions. Some families have been here for generations, and a few don’t appreciate the influx of low-paid state workers buying cookie-cutter tract homes (like mine) here.

The city center is isolated, twelve miles from the freeway and twenty miles away from every other town in the south county. If a fictional story were set in this town, it would feature the same political and religious schisms that divide the rest of our country. There are other tensions. Some families have been here for generations, and a few don’t appreciate the influx of low-paid state workers buying cookie-cutter tract homes (like mine) here. Two inches of rain fell the day we moved into our brand-new home in 2005, making moving our furniture into this house a misery. Our new house had no landscaping and rose from a sea of mud and rocks. With a lot of effort, we made a pleasant yard. When the housing bubble burst in 2008, many people on my side of the street lost their jobs, and some homes went into foreclosure.

Two inches of rain fell the day we moved into our brand-new home in 2005, making moving our furniture into this house a misery. Our new house had no landscaping and rose from a sea of mud and rocks. With a lot of effort, we made a pleasant yard. When the housing bubble burst in 2008, many people on my side of the street lost their jobs, and some homes went into foreclosure. Our main street, Sussex, passes through a historic district. The buildings are all built from sandstone quarried at the old quarries. Many of the old buildings are home to antique stores. The masonic lodge is made of Tenino sandstone.

Our main street, Sussex, passes through a historic district. The buildings are all built from sandstone quarried at the old quarries. Many of the old buildings are home to antique stores. The masonic lodge is made of Tenino sandstone.

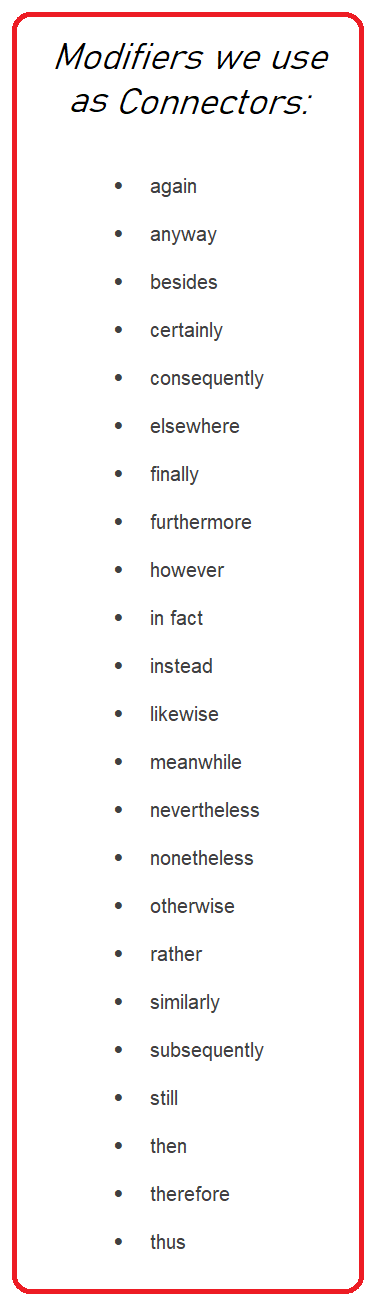

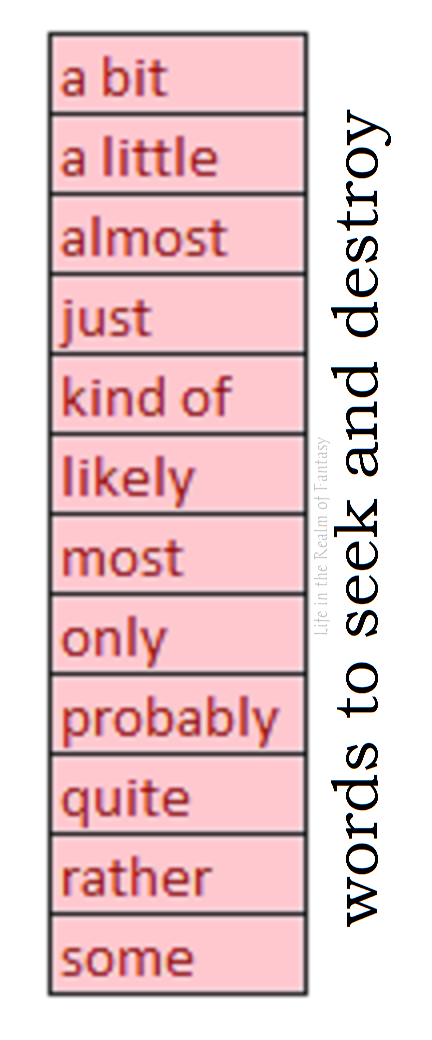

In writing, we add depth and contour to our prose by how we choose and use our words. We “paint” a scene using words to show what the point-of-view character is seeing or experiencing. Yes, we do need to use some modifiers and descriptors.

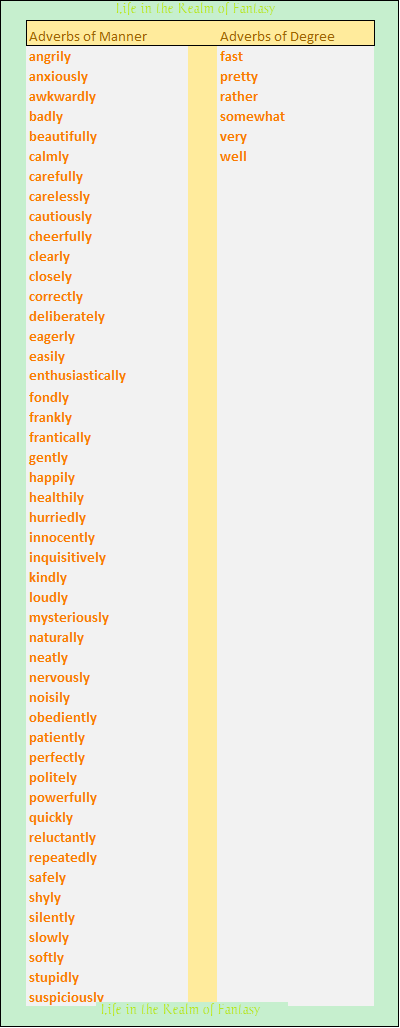

In writing, we add depth and contour to our prose by how we choose and use our words. We “paint” a scene using words to show what the point-of-view character is seeing or experiencing. Yes, we do need to use some modifiers and descriptors. One of the cautions those of us new to the craft frequently hear are criticisms about the number of modifiers (adjectives and adverbs) we habitually use. This can hurt, especially if we don’t understand what the members of our writing group are trying to tell us.

One of the cautions those of us new to the craft frequently hear are criticisms about the number of modifiers (adjectives and adverbs) we habitually use. This can hurt, especially if we don’t understand what the members of our writing group are trying to tell us. In the above sentence, the essential parts are structured this way: noun – verb (sunlight glared), adjective – noun (cold fire), verb – adjective – noun (cast no warmth), and finally, verb-article-noun (burned the eyes). Lead with the action or noun, follow with a strong modifier, and the sentence conveys what is intended but isn’t weakened by the modifiers.

In the above sentence, the essential parts are structured this way: noun – verb (sunlight glared), adjective – noun (cold fire), verb – adjective – noun (cast no warmth), and finally, verb-article-noun (burned the eyes). Lead with the action or noun, follow with a strong modifier, and the sentence conveys what is intended but isn’t weakened by the modifiers.

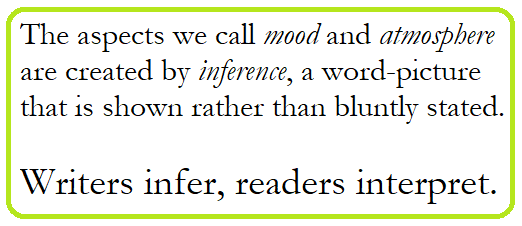

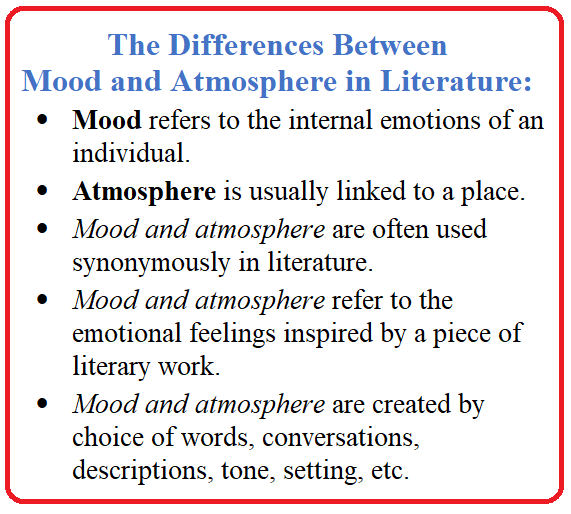

Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood affects (and is affected by) the emotions evoked within the story.

Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood affects (and is affected by) the emotions evoked within the story. Undermotivated emotions lack credibility and leave the reader feeling as if the story is flat. In real life, we have deep, personal reasons for our feelings, and so must our characters.

Undermotivated emotions lack credibility and leave the reader feeling as if the story is flat. In real life, we have deep, personal reasons for our feelings, and so must our characters. Robert McKee tells us that the mood/dynamic of any story is there to make the emotional experience of our characters specific. It makes their emotions feel natural. After all, the mood and atmosphere

Robert McKee tells us that the mood/dynamic of any story is there to make the emotional experience of our characters specific. It makes their emotions feel natural. After all, the mood and atmosphere