This is part two of a series on writing short fiction. One of my favorite forms of short fiction to read is the narrative essay. For indie authors who wish to earn actual money from their writing, the narrative essay is often more salable and appeals to a broader audience.

Narrative essays are drawn directly from real life, but they are fictionalized accounts. They detail an incident or event and talk about how the experience affected the author on a personal level.

Narrative essays are drawn directly from real life, but they are fictionalized accounts. They detail an incident or event and talk about how the experience affected the author on a personal level.

One of my favorite narrative essays is 1994’s Ticket to the Fair (now titled “Getting Away from Already Being Pretty Much Away from It All“) by David Foster Wallace, published in Harpers. I’ve talked about this particular piece before. It’s a humorous, eye-opening story of a naïve, slightly arrogant young journalist’s assignment to cover the 1993 Iowa State Fair, told in the first person.

Wikipedia summarizes Ticket to the Fair this way: Wallace’s experiences and opinions on the 1993 Illinois State Fair, ranging from a report on competitive baton twirling to speculation on how the Illinois State Fair is representative of Midwestern culture and its subsets. Rather than take the easy, dismissive route, Wallace focuses on the joy this seminal midwestern experience brings those involved.

Wallace went to the fair thinking it would be a boring event featuring farm animals, which might be beneath him. But it was his first official assignment for Harpers, and he didn’t want to screw it up. What he found there, the people he met, their various crafts, and how they loved their lives profoundly affected him, altering his view of himself and his values.

Wallace went to the fair thinking it would be a boring event featuring farm animals, which might be beneath him. But it was his first official assignment for Harpers, and he didn’t want to screw it up. What he found there, the people he met, their various crafts, and how they loved their lives profoundly affected him, altering his view of himself and his values.

As we find in Wallace’s piece, the primary purpose of an essay is thought-provoking content. The narrative essay conveys our ideas in a palatable form, so writing this kind of piece requires authors to think.

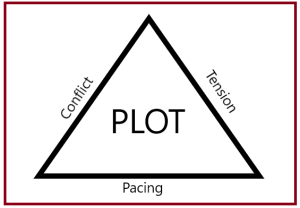

Just like any other form of short fiction, a narrative essay has content and structure. It has

- an introduction,

- a plot,

- characters,

- a setting,

- a climax.

Choose your words for impact because writing with intentional prose is critical. A good narrative essay has been put into an entertaining form that expresses far more than mere opinion. They sometimes offer up deep, uncomfortable views. The trick is to offer them in a way that the reader feels connected to the story. Once they have that connection, they will see the merit of the opinions and viewpoints.

So, narrative essays are a way of sharing our personal view of the world, the places we go, and the people we meet along the way.

- Names should be changed, of course.

Literary magazines want well-written essays on a wide range of topics and life experiences presented with a fresh point of view. Some publications will pay well for first rights.

Literary magazines want well-written essays on a wide range of topics and life experiences presented with a fresh point of view. Some publications will pay well for first rights.

Authors make their names by being published in a reputable magazine. You must pay strict attention to grammar and editing to have any chance of acceptance. Never send out anything that is not your best work.

After you have finished the piece, set it aside for a week or two. Then, return to it with a yellow highlighter and a fresh eye. Print it out and read it aloud, checking for dropped and missing words. In this case, I do NOT recommend the narrator function of your word processing program.

In the process of reading aloud, you will find:

- Spelling—misspelled words, autocorrect errors, and homophones (words that sound the same but are spelled differently). These words are insidious because they are actual words and don’t immediately appear out of place.

- Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These are sneaky and dreadfully difficult to spot. Spell-checker won’t always find them. They make sense to you, the author, because you see what you intended to see. For the reader, they appear as unusually garbled sentences, and you will stumble over them as you read aloud.

- Missing punctuation and closed quotes. These things happen to the best of us.

- Digits/Numbers: Miskeyed numbers are difficult to spot when they are wrong unless they are spelled out.

Don’t be afraid to write with a wide vocabulary, as people who read these publications have a broad command of language.

Don’t be afraid to write with a wide vocabulary, as people who read these publications have a broad command of language.

- However, we never use jargon or technical terms that only people in certain professions would know unless it is a piece for a publication catering to that segment of readers.

Above all, be a little bold. I enjoy reading David Foster Wallace and George Saunders because they are adventurous in their work.

And finally, we must be realistic. Not everything you write will resonate with everyone you submit it to. Put two people in a room, hand them the most exciting thing you’ve ever read, and you’ll get two different opinions. They probably won’t agree with you.

Don’t be discouraged by rejection. I follow several well-known authors via social media because what they have to say about the industry is intriguing. They’re journalists who submit at least one piece weekly, hoping they will sell one or two a year. One says she aims for one hundred rejections a year because two or three stories or essays are bound to strike a chord with the right editor during that time.

Rejection happens far more frequently than acceptance, so don’t let fear of rejection keep you from writing pieces you’re emotionally invested in.

This is where you have the opportunity to cross the invisible line between amateur and professional. Always take the high ground—if an editor has sent you a detailed rejection, respond with a simple “thank you for your time.” If it’s a form letter rejection, don’t reply.

What should you do if your work is accepted but the editor wants a few revisions?

If the editor wants changes, they will make clear what they want you to do. Editors know what their intended audience wants. Trust that the editor knows their business.

If the editor wants changes, they will make clear what they want you to do. Editors know what their intended audience wants. Trust that the editor knows their business.

Make whatever changes they request.

Never be less than gracious to any of the people at a publication when you communicate with them, whether they are the senior editor or the newest intern. Be a team player and work with them.

And when you receive that email of acceptance—celebrate! There is no better feeling than knowing someone you respect liked your work enough to publish it.

Credits and Attributions:

Wikipedia contributors. A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2023 Sep 4, 00:32 UTC [cited 2023 Nov 20]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=A_Supposedly_Fun_Thing_I%27ll_Never_Do_Again&oldid=1173714712.

You are more likely to sell a drabble than a short story in today’s speculative fiction market. You are also more likely to sell a short story than a novel.

You are more likely to sell a drabble than a short story in today’s speculative fiction market. You are also more likely to sell a short story than a novel. does require plotting and rewriting the prose until the entire story is told in exactly 100 words. You should expect to spend an hour or so writing and then editing it to fit within the 100-word constraint.

does require plotting and rewriting the prose until the entire story is told in exactly 100 words. You should expect to spend an hour or so writing and then editing it to fit within the 100-word constraint. The above drabble is a 100-word romance and is an example I have used here before. It has a beginning (hook), a middle (the conflict), and a resolution. The opening shows our protagonist on the beach with someone for whom she cares deeply.

The above drabble is a 100-word romance and is an example I have used here before. It has a beginning (hook), a middle (the conflict), and a resolution. The opening shows our protagonist on the beach with someone for whom she cares deeply. The act of writing random ideas and emotions down in drabble form rejuvenates your creativity, a mini-vacation from your other work. It rests your mind and clears things so you can return to your main project with all your attention.

The act of writing random ideas and emotions down in drabble form rejuvenates your creativity, a mini-vacation from your other work. It rests your mind and clears things so you can return to your main project with all your attention.

![Newell Convers Wyeth [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/boys_king_arthur_-_n-_c-_wyeth_-_p82.jpg?w=239)