Last week, in Monday’s post, ‘The Second Draft – Subtext,‘ we barely skimmed the surface of that aspect of our story. We discussed how it can be conveyed as part of world-building. But subtext is so much more. Subtext is emotion. It’s the hidden story, the hints, allegations, and secret reasoning.

- Subtext is the content that supports both the dialogue and the personal events experienced by the characters.

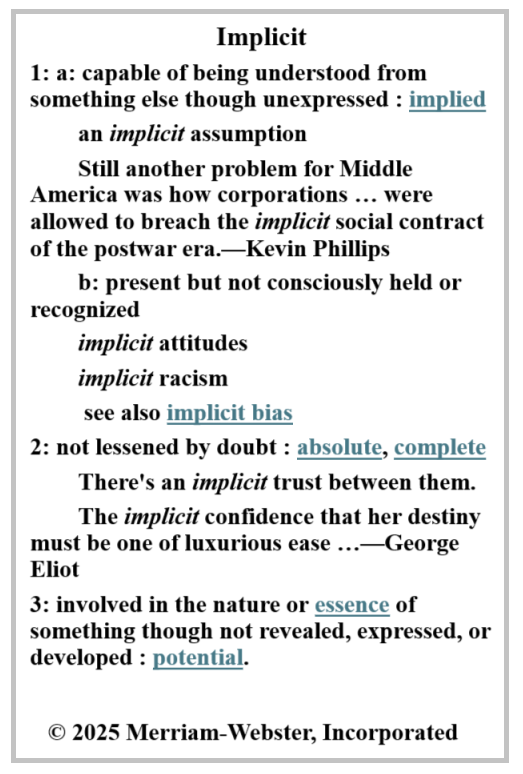

These are implicit ideas and emotions. These thoughts and feelings may or may not be verbalized, as subtext is often conveyed through the unspoken thoughts and motives of characters. It emerges gradually as what a character really thinks and believes.

These are implicit ideas and emotions. These thoughts and feelings may or may not be verbalized, as subtext is often conveyed through the unspoken thoughts and motives of characters. It emerges gradually as what a character really thinks and believes.

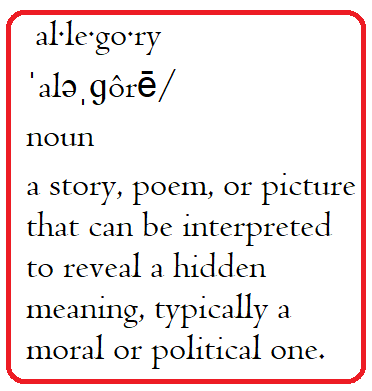

It also shows the larger picture. It can imply controversial subjects, or it can be a simple, direct depiction of motives. Metaphors and allegories are excellent tools for conveying ideas.

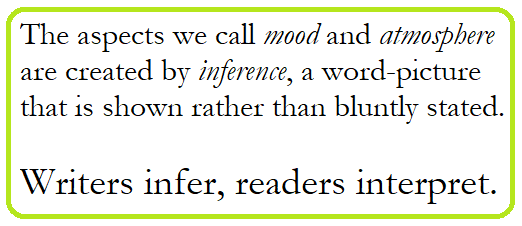

Subtext can be a conscious thought or a gut reaction on the part of the characters. It is imagery as conveyed by the author. A good story is far more than a recounting of ‘he said’ and ‘she said. ‘It’s more than the action and events that form the arc of the story. A good story is all that, but without good subtext, the story never achieves its true potential.

Within our characters, underneath their dialogue, lurks conflict, anger, rivalry, desire, or pride. Joy, pleasure, fear … as the author, we know those emotions are there, but conveying them without beating the reader over the head is where artistry comes into play.

When it’s done right, the subtext conveys backstory with a deft hand. When layered with symbolism and atmosphere, the reader absorbs the subtext on a subliminal level because it is unobtrusive.

An excellent book on this subject is Writing Subtext: What Lies Beneath by Dr. Linda Seger. On the back of this book, subtext is described as “a silent force bubbling up from below the surface of any screenplay or novel.” This book is a valuable resource for discovering and conveying the deeper story that underlies the action.

An excellent book on this subject is Writing Subtext: What Lies Beneath by Dr. Linda Seger. On the back of this book, subtext is described as “a silent force bubbling up from below the surface of any screenplay or novel.” This book is a valuable resource for discovering and conveying the deeper story that underlies the action.

Some writers assume that heavy-handed information dumping is subtext because it is often conveyed through internal dialogue,

It’s not. Descriptions, opinions, gestures, imagery, and yes – subtext – can be conveyed in dialogue, but dialogue itself is just people talking.

When characters constantly verbalize their every thought, you run into several problems. First, verbalizing thoughts can become an opportunity for an info dump. Second, in genre fiction, the accepted method of conveying internal dialogue (thought) is through the use of italics.

The main problem I have with italics is that when a writer expresses a character’s thoughts, a wall of leaning letters is difficult to decipher.

Nevertheless, thoughts (internal dialogue) have their place in the narrative and can be part of the subtext. However, I recommend going lightly with them. There are other ways to convey thoughts. In the years since I first began writing seriously, I’ve evolved in my writing habits. Nowadays, I am increasingly drawn to using the various forms of free indirect speech to show who my characters think they are and how they see their world. I rarely use italics.

A character’s backstory is the subtext of their memories and the events that led them to the situation in which they find themselves. We use interior monologues to represent a character’s thoughts in real time, as they actually think them in their head, using the precise words they use. For that reason, italicized thoughts are always written in first-person present tense: I’m the queen! We don’t think about ourselves in the third person, even if we really are the queen.

A character’s backstory is the subtext of their memories and the events that led them to the situation in which they find themselves. We use interior monologues to represent a character’s thoughts in real time, as they actually think them in their head, using the precise words they use. For that reason, italicized thoughts are always written in first-person present tense: I’m the queen! We don’t think about ourselves in the third person, even if we really are the queen.

We think in the first-person present tense because we are in the middle of events as they happen. Our lives unfold in the “now,” so they are written as the character experiences them.

Memories are subtext and reflect a moment in the past. They should be written in the past tense to reflect that. If it was a moment that changed their life, consider rewriting it as a scene and have the character relive it.

We can combine memories and emotions in the form of free indirect speech:

Jeanne paused. The sight of that dark entrance brought a wave of memories, all of them dark and painful.

Chris, on his knees sobbing … their mother’s bloody form ….

She was too young to understand then, but now she knew why Chris seemed so emotionless at times.

Resolutely, she followed him inside.

Subtext expressed as thoughts must fit as smoothly into the narrative as conversations. My recommendation is to express only the most important thoughts through an internal monologue, which will help you retain the reader’s interest. The rest can be presented in images that build the world around the characters.

Information is a component of subtext. We have provided the reader with a lot of information in only a few sentences. They might think they know who a character is, and they have a clue about his aspirations.

Information is a component of subtext. We have provided the reader with a lot of information in only a few sentences. They might think they know who a character is, and they have a clue about his aspirations.

But a good story keeps us hanging. Knowledge must emerge via subtext and through descriptions of the environment, conversations, interior monologues, and a character’s general impressions of the world around them.

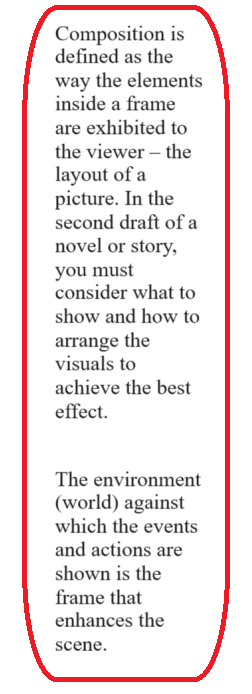

Odors and ambient sounds, objects placed in a scene, sensations of wind, or the feeling of heat when the sun shines through a window. These bits of background are subtext.

I like books where the scenery is shown in brief impressions, and the reader sees exactly what needs to be there. We don’t want to distract our readers by including unimportant things, such as the exact number of ferns in a forest clearing. The ferns are there, the lost hiker thinks eating their tips is better than starving, and that is all the reader wants to know.

Subtext, metaphor, and allegory are impressions and images that build the world around and within the characters. They are as fundamental to the story as the plot and the arc of the story. As a reader, I’m always thrilled to read a novel that is a voyage of discovery, and good subtext makes that happen.