Emotions are tricky to convey, and I’ve read a few books lately where this was poorly handled (he was angry, she was enraged, etc.). So, today, I want to revisit a post from August 2021 that examined this problem.

When we write about mild reactions, wasting words on too much description is unnecessary because mild is boring. But if you want to emphasize the chemistry between two characters, good or bad, strong gut reactions on the part of your protagonist are a good way to do so.

When we write about mild reactions, wasting words on too much description is unnecessary because mild is boring. But if you want to emphasize the chemistry between two characters, good or bad, strong gut reactions on the part of your protagonist are a good way to do so.

I often use examples of how to convey simple emotions from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. First, you haven’t gotten the real story if you haven’t read the book but have seen the various movie adaptations. Adaptations are stories that have been reworked, so it never hurts to go to the source material and discover what the author intended.

The prose has power despite the fact it was written a century ago. I don’t feel qualified to get into the debate over whether Fitzgerald stole prose from Zelda or not. Their relationship was a hot mess. I’m a casual reader, not a scholar, so I leave that can of worms to those more knowledgeable.

However, we can learn from how the prose was constructed and how Nick Carraway sees the world. There are lessons here, things we can put into action in our own work.

About The Great Gatsby, via Wikipedia:

The Great Gatsby is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts first-person narrator Nick Carraway‘s interactions with mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby and Gatsby’s obsession to reunite with his former lover, Daisy Buchanan.

The novel was inspired by a youthful romance Fitzgerald had with socialite Ginevra King and the riotous parties he attended on Long Island’s North Shore in 1922. Following a move to the French Riviera, Fitzgerald completed a rough draft of the novel in 1924. He submitted it to editor Maxwell Perkins, who persuaded Fitzgerald to revise the work over the following winter. After making revisions, Fitzgerald was satisfied with the text, but remained ambivalent about the book’s title and considered several alternatives. Painter Francis Cugat‘s cover art greatly impressed Fitzgerald, and he incorporated aspects of it into the novel. [1]

If you are curious, an excellent book on Sara and Gerald Murphy, the people who inspired Fitzgerald’s novels (and a glimpse into the real world he introduces us to), is Everybody Was So Young: Gerald and Sara Murphy: A Lost Generation Love Story by Amanda Vail.

The following passages show us what is happening inside Nick Carraway, the protagonist. Every word is intentional, chosen, and placed so as to evoke the strongest reaction in the reader.

Here, Fitzgerald describes a feeling of hopefulness:

And so with the sunshine and the great bursts of leaves growing on the trees—just as things grow in fast movies—I had that familiar conviction that life was beginning over again with the summer.

Next, he describes shock:

It never occurred to me that one man could start to play with the faith of fifty million people—with the single-mindedness of a burglar blowing a safe.

Jealousy:

Her expression was curiously familiar—it was an expression I had often seen on women’s faces but on Myrtle Wilson’s face it seemed purposeless and inexplicable until I realized that her eyes, wide with jealous terror, were fixed not on Tom, but on Jordan Baker, whom she took to be his wife.

The discomfort of witnessing a marital squabble:

The prolonged and tumultuous argument that ended by herding us into that room eludes me, though I have a sharp physical memory that, in the course of it, my underwear kept climbing like a damp snake around my legs and intermittent beads of sweat raced cool across my back.

Fitzgerald shows us Nick’s emotions, AND we see his view of everyone else’s emotions. We see their physical reactions through his eyes and through visual cues and conversations.

Fitzgerald shows us Nick’s emotions, AND we see his view of everyone else’s emotions. We see their physical reactions through his eyes and through visual cues and conversations.

Nick Carraway’s story is told in the first person, and Fitzgerald stays in character throughout the narrative.

I suggest playing with narrative POV until you find the best one. Sometimes, a story falls out of my head in the first person, and other times, not. Whether we are writing in the first-person or close third-person point of view, seeing the reactions of others is key to conveying the sometimes-tumultuous dynamics of any group.

Writing emotions with depth is a balancing act. The internal indicator of a particular emotion is only half the story. We see those reactions in the characters’ body language.

This is where we write from real life. When someone is happy, what do you see on the outside? When a friend looks happy, you assume you know what they feel.

I spend a great deal of time working on prose, attempting to combine the surface of the emotion (physical) with the deeper aspect of the emotion (internal). I want to write it so I’m not telling the reader what to experience.

Great authors allow the reader to decide what to feel. They make the emotion seem as if it is the reader’s feeling.

If you have no idea how to begin showing the basic emotions of your characters, a good handbook that offers a jumping-off point is The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi.

If you have no idea how to begin showing the basic emotions of your characters, a good handbook that offers a jumping-off point is The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi.

Their entire series of Writers Helping Writers books is affordable and full of hints for adding depth to your characters.

Just don’t go overboard. These books will offer nine or ten hints that are physical indications for a wide range of surface emotions. You can usually avoid dragging the reader through numerous small facial changes in a scene simply by giving their internal reactions a little thought.

I usually reread The Great Gatsby and several other classic novels in various genres every summer.

Fitzgerald’s prose is written in the literary style of the 1920s. It was a time in which we still liked words and the many ways they could be used and abused, hence the massive amount of Jazz Age slang that seems incomprehensible to us only a century later.

If you’re like me, you might need to find a bit of a translation for some of the slang: 20’s Slang | the-world-of-gatsby (15anniegraves.wixsite.com). The problem of slang falling out of fashion as quickly as it enters everyday speech is an excellent reason to avoid using it.

For example, one bit of slang confused me because of the context in which it was used: Police dog. It was a slang noun referring to a young man to whom one is engaged.

Myrtle Wilson said “I’d like to get one of those police dogs.”

When I read it the first time, I thought the speaker meant a German shepherd, and it didn’t make sense.

Students taking college-level classes in literature and English are often required to read The Great Gatsby and other classic novels from that era, such as James Joyce’s Ulysses. Reading classic literature as a group and discussing every aspect is central to understanding it. Also, you get a glossary as part of the course, so that’s a bonus.

Students taking college-level classes in literature and English are often required to read The Great Gatsby and other classic novels from that era, such as James Joyce’s Ulysses. Reading classic literature as a group and discussing every aspect is central to understanding it. Also, you get a glossary as part of the course, so that’s a bonus.

While these novels are too complex for most people’s casual reading, I wanted to understand how these books were constructed.

We twenty-first-century writers can learn something important from studying how Fitzgerald showed his characters’ thoughts and internal reactions. My personal goal is to improve how my first drafts read.

Who knows if I will succeed–but I’ll have fun trying.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “The Great Gatsby,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Great_Gatsby&oldid=1190673325 (accessed January 10, 2024).

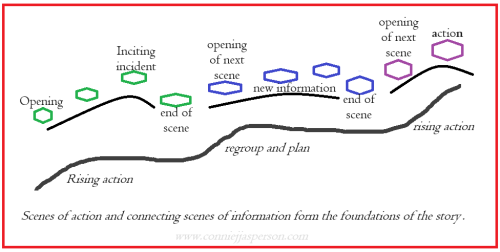

After we survive the middle crisis, we have falling action. We receive the crucial information, the characters regroup, and we experience the unfolding of events leading to the conclusion. The protagonist’s problems are resolved, and we (the readers) are offered a good ending and closure.

After we survive the middle crisis, we have falling action. We receive the crucial information, the characters regroup, and we experience the unfolding of events leading to the conclusion. The protagonist’s problems are resolved, and we (the readers) are offered a good ending and closure. These small arcs of action, reaction, and calm push the plot and ensure it doesn’t stall. Each scene is an opportunity to ratchet up the tension and increase the overall conflict that drives the story.

These small arcs of action, reaction, and calm push the plot and ensure it doesn’t stall. Each scene is an opportunity to ratchet up the tension and increase the overall conflict that drives the story. Transition scenes must also have an arc supporting the cathedral that is our novel. They will begin, rise to a peak as the necessary information is discussed, and ebb when the characters move on.

Transition scenes must also have an arc supporting the cathedral that is our novel. They will begin, rise to a peak as the necessary information is discussed, and ebb when the characters move on. Plots are driven by an imbalance of power. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information.

Plots are driven by an imbalance of power. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information. When we write a story, no matter the length, we hope the narrative will keep our readers interested until the end of the book. We lure readers into the scene and reward them with a tiny dose of new information.

When we write a story, no matter the length, we hope the narrative will keep our readers interested until the end of the book. We lure readers into the scene and reward them with a tiny dose of new information. If you have been a computer user for any length of time, you know that hardware failure, virus attacks by hackers, and other computer disasters will happen. They’re like the

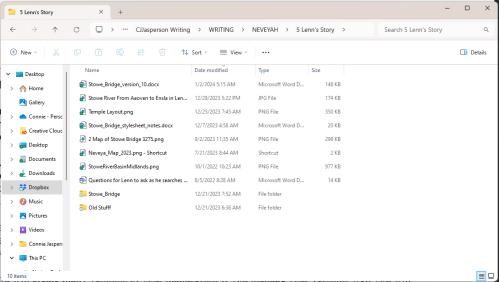

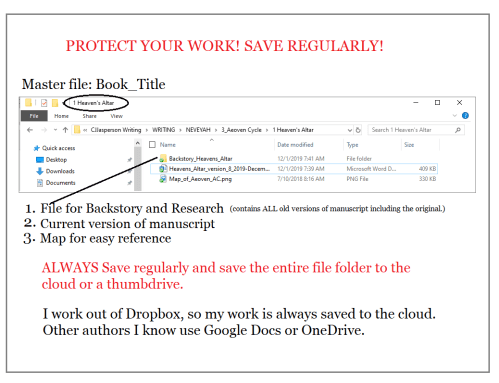

If you have been a computer user for any length of time, you know that hardware failure, virus attacks by hackers, and other computer disasters will happen. They’re like the  This year, I met a young man who, being new to using a word processing program, forgot how he named his 2022 manuscript. He couldn’t find it when he decided to start writing again. I showed him how to search for files by date, taught him how to name documents, and taught him how to create a master file for all the files generated in the process of writing his book.

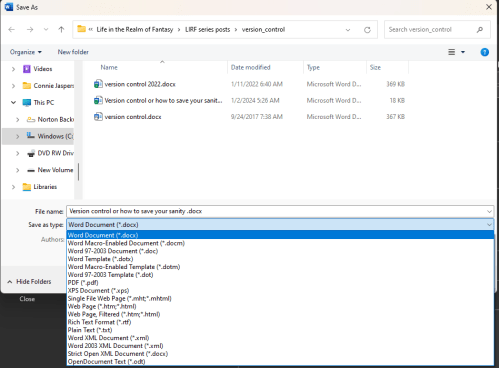

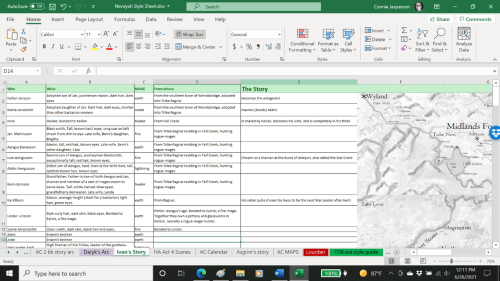

This year, I met a young man who, being new to using a word processing program, forgot how he named his 2022 manuscript. He couldn’t find it when he decided to start writing again. I showed him how to search for files by date, taught him how to name documents, and taught him how to create a master file for all the files generated in the process of writing his book. I work out of Dropbox, so when I save and close a document, my work is automatically saved and backed up to

I work out of Dropbox, so when I save and close a document, my work is automatically saved and backed up to  One thing I hear from new writers is how surprised they are at how easily something that should be simple can veer out of control. The worst thing that can happen to an author is accidentally saving an old file over the top of your new file or deleting the file entirely.

One thing I hear from new writers is how surprised they are at how easily something that should be simple can veer out of control. The worst thing that can happen to an author is accidentally saving an old file over the top of your new file or deleting the file entirely. I make a separate subfolder for my work when it’s in the editing process. That subfolder contains two subfolders, and one is for the chapters my editor sends me in their raw state with all her comments:

I make a separate subfolder for my work when it’s in the editing process. That subfolder contains two subfolders, and one is for the chapters my editor sends me in their raw state with all her comments:

We are at the same latitude as Paris, Zurich, and Montreal but usually get a lot more rain than those cities. The North Pacific can be wild at this time of the year, which makes for some great storm-watching.

We are at the same latitude as Paris, Zurich, and Montreal but usually get a lot more rain than those cities. The North Pacific can be wild at this time of the year, which makes for some great storm-watching. By the time the authors got to the meat of the matter (which was late in the second half) I no longer cared. Truthfully, when the fluff is carved away from this book, you might have 20,000 or so words of an interesting story—a novella.

By the time the authors got to the meat of the matter (which was late in the second half) I no longer cared. Truthfully, when the fluff is carved away from this book, you might have 20,000 or so words of an interesting story—a novella. I’m planning two volumes because one will feature stories set in the world of Neveyah, and the other will be random speculative short fiction pieces.

I’m planning two volumes because one will feature stories set in the world of Neveyah, and the other will be random speculative short fiction pieces.

I have talked about this novella many times, as I consider it one of the most enduring stories in Western literature. The opening act of this tale is a masterclass in how to structure a story.

I have talked about this novella many times, as I consider it one of the most enduring stories in Western literature. The opening act of this tale is a masterclass in how to structure a story. “Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.”

“Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.” As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens says differently.

As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens says differently.

I have planned the menu for Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, but a few things still need some forethought if I want those gatherings to go well. We’ve been invited to a New Year’s Eve potluck. I’m torn between making an avocado-cucumber-tomato salad or stuffed mushrooms—both are easy.

I have planned the menu for Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, but a few things still need some forethought if I want those gatherings to go well. We’ve been invited to a New Year’s Eve potluck. I’m torn between making an avocado-cucumber-tomato salad or stuffed mushrooms—both are easy. No more tape in my hair, no more naughty words, and no more hunting for the scissors I just had in my hands.

No more tape in my hair, no more naughty words, and no more hunting for the scissors I just had in my hands. This is my recipe for the most delicious ONION AND MUSHROOM GRAVY:

This is my recipe for the most delicious ONION AND MUSHROOM GRAVY: 1 bag bread cubes for stuffing, or 10 cups 1/2 inch bread cubes from 1 large loaf of day-old wheat or other sandwich bread. Sometimes I bake my own bread, sometimes not.

1 bag bread cubes for stuffing, or 10 cups 1/2 inch bread cubes from 1 large loaf of day-old wheat or other sandwich bread. Sometimes I bake my own bread, sometimes not.

That timeless story was written in 1843 as a serialized novella. It has inspired a landslide of adaptations in both movies and books and remains one of the most beloved tales of redemption in the Western canon.

That timeless story was written in 1843 as a serialized novella. It has inspired a landslide of adaptations in both movies and books and remains one of the most beloved tales of redemption in the Western canon. I wish he could have seen how beloved his creation is now, one hundred and eighty years later.

I wish he could have seen how beloved his creation is now, one hundred and eighty years later. Charles Dickens showed us that charity and generosity to those less fortunate must become a year-round emotion. Our local community is a good place to start.

Charles Dickens showed us that charity and generosity to those less fortunate must become a year-round emotion. Our local community is a good place to start. However, this year, I am experiencing something I haven’t before—the post-NaNoWriMo slump. My creativity levels are low, and my words seem reluctant to join the party. I know many authors who suffer through this, but since I began this journey in 2010, I have never experienced it.

However, this year, I am experiencing something I haven’t before—the post-NaNoWriMo slump. My creativity levels are low, and my words seem reluctant to join the party. I know many authors who suffer through this, but since I began this journey in 2010, I have never experienced it. My first drafts tend to be ugly. The story emerges from my imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard), warts and all. Each first draft I can write “the end” on is a hot mess of repetitions, awkward phrasing, and cut-and-paste errors. I set them aside when they’re complete and often forget I’ve written them.

My first drafts tend to be ugly. The story emerges from my imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard), warts and all. Each first draft I can write “the end” on is a hot mess of repetitions, awkward phrasing, and cut-and-paste errors. I set them aside when they’re complete and often forget I’ve written them. Then, I turn to the last paragraph on the story’s final page and cover the rest of the page with a sheet of paper. I begin reading again, starting with the ending paragraph, working my way forward, and making notes in the margins.

Then, I turn to the last paragraph on the story’s final page and cover the rest of the page with a sheet of paper. I begin reading again, starting with the ending paragraph, working my way forward, and making notes in the margins. It works the same way for novels. I print out each chapter and go through the steps I described above. Then, I make the revisions in a new file labeled with the date and the word “revised.”

It works the same way for novels. I print out each chapter and go through the steps I described above. Then, I make the revisions in a new file labeled with the date and the word “revised.” You can get fancy and use a dedicated writer’s program like

You can get fancy and use a dedicated writer’s program like  But we’d prefer the snow to stay in the mountains where it belongs. Something about the slightest dusting sends the Pacific Northwest into a panic.

But we’d prefer the snow to stay in the mountains where it belongs. Something about the slightest dusting sends the Pacific Northwest into a panic. BBC: From memoir and self-care books to comic novels, writing about our flaws and imperfections has never been so popular. But can failing ever be a success? Lindsay Baker explores this question. Read the story here:

BBC: From memoir and self-care books to comic novels, writing about our flaws and imperfections has never been so popular. But can failing ever be a success? Lindsay Baker explores this question. Read the story here:  Also from Publishers Weekly: A confident mood prevailed among independent booksellers over this November holiday sales weekend. (…) Sales data from

Also from Publishers Weekly: A confident mood prevailed among independent booksellers over this November holiday sales weekend. (…) Sales data from