Artist: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

Artist: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

Title: Gassed

Date: 1919

Medium: oil on canvas

Dimensions: Height: 231 cm (90.9 in); Width: 611.1 cm (20 ft)

Writing Prompt: November is once again upon us, the month when many people are inspired to begin their writing career. But what shall we write about?

John Singer Sargent tells many stories in this one powerful statement about war and the inhumanity of humankind. He also lays bare our resilience, our drive to survive. What thoughts, what ideas are prompted by what you see here?

What I love about this painting:

I first featured this painting in 2021 and have gone back to it every year since. This is a deeply moving antiwar statement that only John Singer Sargent could have shown us. He was commissioned as a war artist by the British Ministry of Information. He illustrated numerous scenes from the Great War. Sargent had been deeply affected by what he had seen while touring the front in France and by the death of his niece Rose-Marie in the shelling of the St Gervais church, Paris, on Good Friday 1918.

John Singer Sargent was a complicated man, as most artists are. Famous as a portrait artist, he painted landscapes that conveyed a sense of mood and emotion that few of his contemporaries could match.

The colors are muted, and even the pastels are dark and dirty. The suffering of the maimed and injured men is laid bare. Through the legs of the walking wounded, the rising moon illuminates the desire of the uninjured to try to find some normalcy. Dwarfing the players and their game, the vast sea of dead and injured stretches as far as the eye can see.

Above, two tiny figures represent the clash of biplanes in the distance, the ever-moving machine of death and inhumanity that is war.

About this painting, via Wikipedia:

[1] Gassed is a very large oil painting completed in March 1919 by John Singer Sargent. It depicts the aftermath of a mustard gas attack during the First World War, with a line of wounded soldiers walking towards a dressing station. Sargent was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee to document the war and visited the Western Front in July 1918 spending time with the Guards Division near Arras, and then with the American Expeditionary Forces near Ypres. The painting was finished in March 1919 and voted picture of the year by the Royal Academy of Arts in 1919. It is now held by the Imperial War Museum. It visited the US in 1999 for a series of retrospective exhibitions, and then from 2016 to 2018 for exhibitions commemorating the centenary of the First World War.

The painting measures 231.0 by 611.1 centimeters (7 ft 6.9 in × 20 ft 0.6 in). The composition includes a central group of eleven soldiers depicted nearly life-size. Nine wounded soldiers walk in a line, in three groups of three, along a duckboard towards a dressing station, suggested by the guy ropes to the right side of the picture. Their eyes are bandaged, blinded by the effect of the gas, so they are assisted by two medical orderlies. The line of tall, blind soldiers forms a naturalist allegorical frieze, with connotations of a religious procession. Many other dead or wounded soldiers lie around the central group, and a similar train of eight wounded, with two orderlies, advances in the background. Biplanes dogfight in the evening sky above, as a watery setting sun creates a pinkish yellow haze and burnishes the subjects with a golden light. In the background, the moon also rises, and uninjured men play association football in blue and red shirts, seemingly unconcerned at the suffering all around them.

The painting provides a powerful testimony of the effects of chemical weapons, vividly described in Wilfred Owen‘s poem Dulce et Decorum Est. Mustard gas is a persistent vesicant gas, with effects that only become apparent several hours after exposure. It attacks the skin, the eyes and the mucous membranes, causing large skin blisters, blindness, choking and vomiting. Death, although rare, can occur within two days, but suffering may be prolonged over several weeks.

Sargent’s painting refers to Bruegel’s 1568 work The Parable of the Blind, with the blind leading the blind, and it also alludes to Rodin’s Burghers of Calais.

About the Artist, via Wikipedia:

[2] John Singer Sargent (January 12, 1856 – April 14, 1925) was an American expatriate artist, considered the “leading portrait painter of his generation” for his evocations of Edwardian-era luxury. He created roughly 900 oil paintings and more than 2,000 watercolors, as well as countless sketches and charcoal drawings. His oeuvre documents worldwide travel, from Venice to the Tyrol, Corfu, the Middle East, Montana, Maine, and Florida.

Born in Florence to American parents, he was trained in Paris before moving to London, living most of his life in Europe. He enjoyed international acclaim as a portrait painter. An early submission to the Paris Salon in the 1880s, his Portrait of Madame X, was intended to consolidate his position as a society painter in Paris, but instead resulted in scandal. During the next year following the scandal, Sargent departed for England where he continued a successful career as a portrait artist.

From the beginning, Sargent’s work is characterized by remarkable technical facility, particularly in his ability to draw with a brush, which in later years inspired admiration as well as criticism for a supposed superficiality. His commissioned works were consistent with the grand manner of portraiture, while his informal studies and landscape paintings displayed a familiarity with Impressionism. In later life Sargent expressed ambivalence about the restrictions of formal portrait work, and devoted much of his energy to mural painting and working en plein air. Art historians generally ignored artists who painted royalty and “society” – such as Sargent – until the late 20th century. [2]

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Gassed (painting),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gassed_(painting)&oldid=1029966714 (accessed July 15, 2021).

[2] Wikipedia contributors, “John Singer Sargent,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=John_Singer_Sargent&oldid=1032671314 (accessed July 15, 2021).

Image source: File:Sargent, John Singer (RA) – Gassed – Google Art Project.jpg – Wikipedia (accessed July 15, 2021).

Title: Selling Christmas Trees

Title: Selling Christmas Trees

![Upon Sunny Waves, by Hans Dahl PD|70 [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/hans_dahl_-_upon_sunny_waves.jpg?w=500)

Artist: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

Artist: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

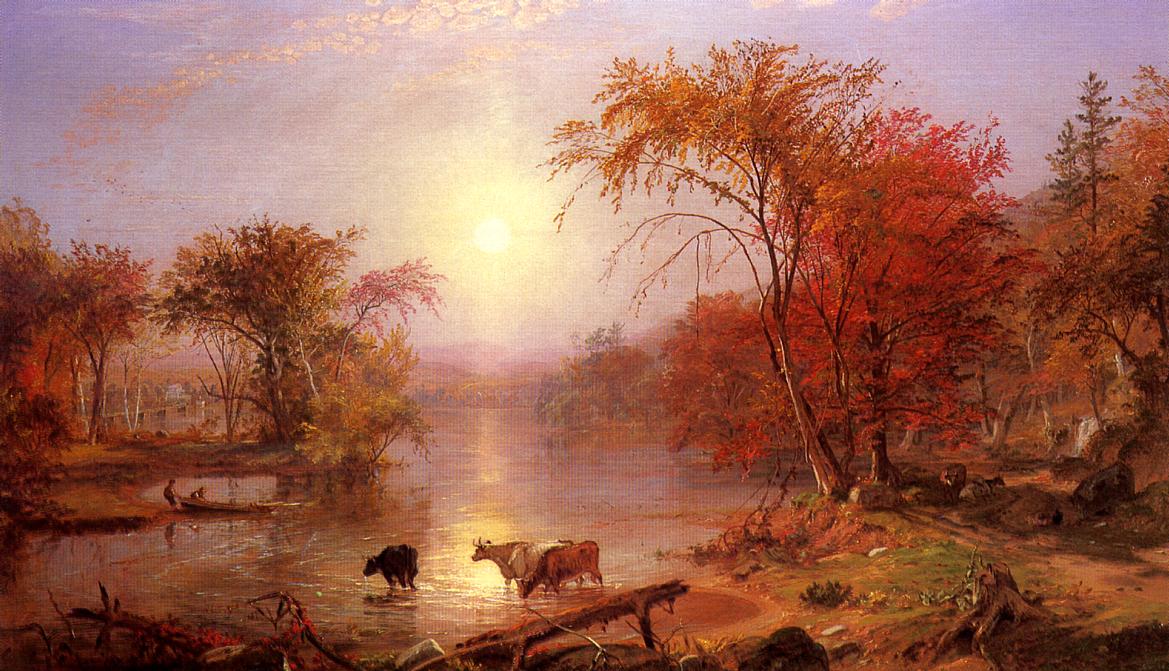

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)![Falling Leaves, by Olga Wisinger-Florian, ca 1899 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/olga_wisinger-florian_-_falling_leaves.jpg)