If you want to succeed at completing a project with the ambitious goal of writing a novel, I suggest planning in advance. I have mentioned before that I like to storyboard all my ideas.

That way, if I become lost or find myself floundering in the writing process, I can come back to my stylesheet and remind myself of the original concept of the story.

That way, if I become lost or find myself floundering in the writing process, I can come back to my stylesheet and remind myself of the original concept of the story.

Many people use Scrivener for this, but I was a bookkeeper for most of my working years, so I still use a spreadsheet program. Excel works for me because I have used Microsoft products since the early nineties and am comfortable with that program.

Some people use a whiteboard, and others use Post-It Notes or a combination of the two.

Scrivener currently (in 2025) costs around $60.00, which is not too bad. I have never invested in it, but some of my friends swear by it. On the good side, they have a 30-day free trial period, so if you are interested, test it out. #1 Novel & Book Writing Software For Writers

However, Google Drive has a free program called Google Sheets. This program is similar to Excel (which I use), so the principles I will be discussing are the same.

Admittedly, this program doesn’t do what Excel does, but it is perfect for this if you don’t have Microsoft Office.

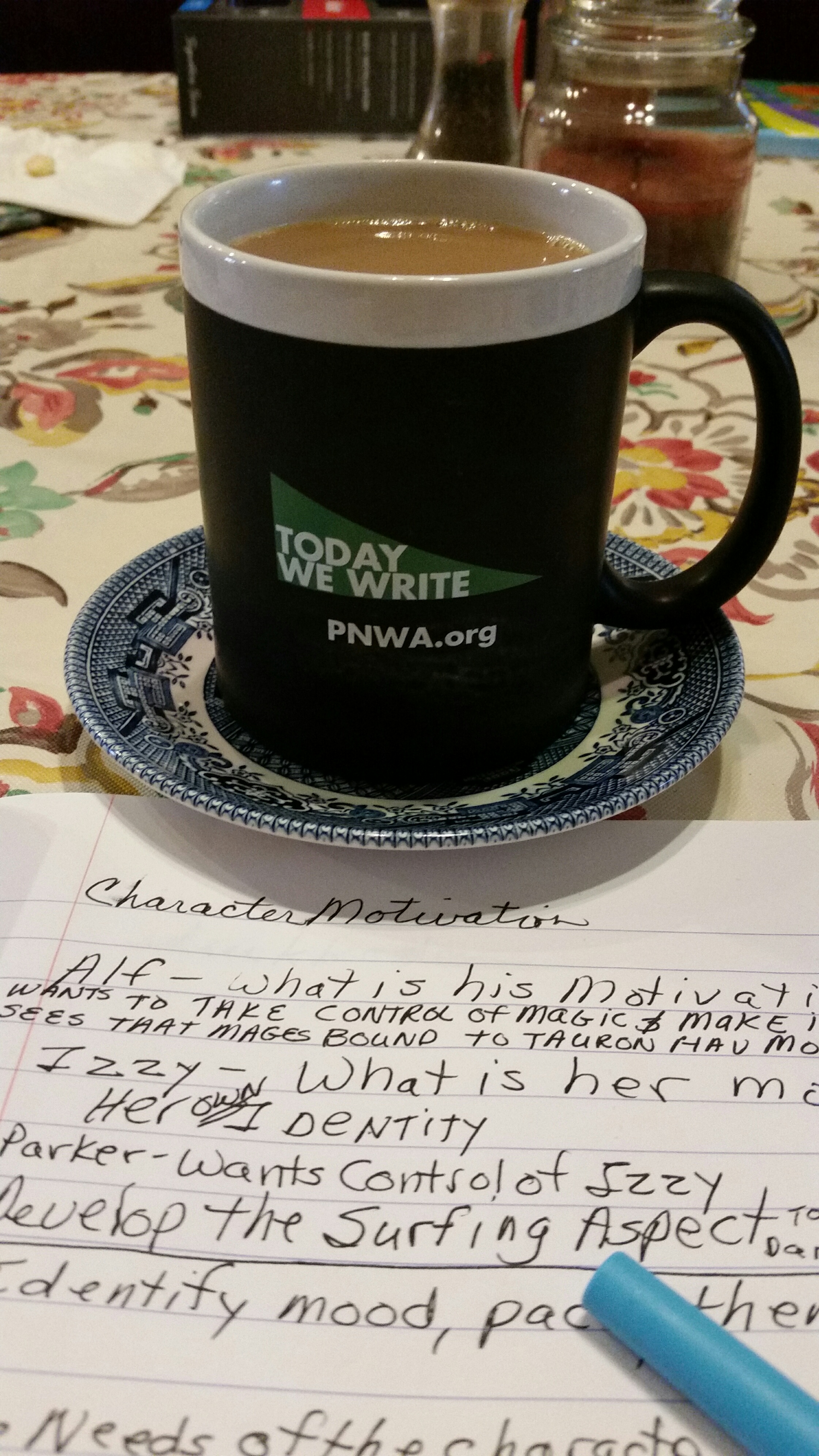

However, you can create a stylesheet in any way that makes you happy, even using a notepad and a pencil.

The important thing is to organize your plot notes, research, and background materials in a way that is accessible and makes sense to you.

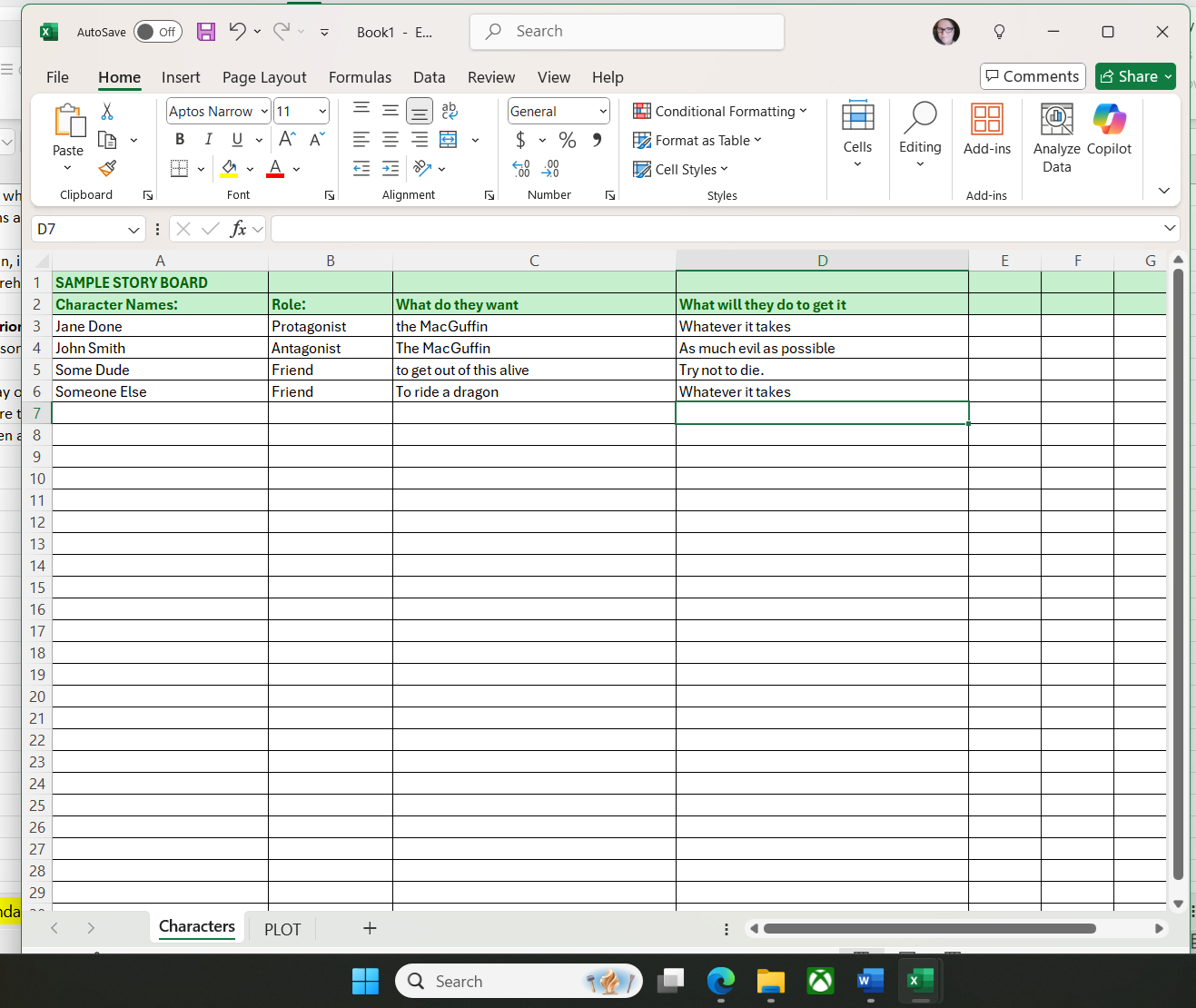

On line one of page one – I give my project a working title and write that at the top of the spreadsheet (line 1). I save it with that label, something like Strange_story_stylesheet_05-May-2025. That label tells me three things: Working title (Strange Story), type of document (stylesheet), and date begun (May 5, 2025).

- If my outline is an idea for a short story meant for a specific purpose, I include the intended publication and closing date for submissions. (This is necessary for anthologies but not needed for a novel)

On line two, I label my columns with the categories listed below. Then, on the ribbon, I open the view tab, highlight the third row, and click freeze panes. This allows me to scroll down the spreadsheet while keeping the title and column headings visible.

Page one of my storyboard works this way: I make a list of names and places with four pieces of information pertaining to the story, all on the same line.

Column A heading – Character Names: list the important characters by name and also list the important places where the story will be set.

Column B heading – Role: What their role is, a note about that person or place, a brief description of who and what they are.

Column C heading – What do they want? What does each character desire?

Column D heading – What will they do to get it? How far will they go to achieve their desire?

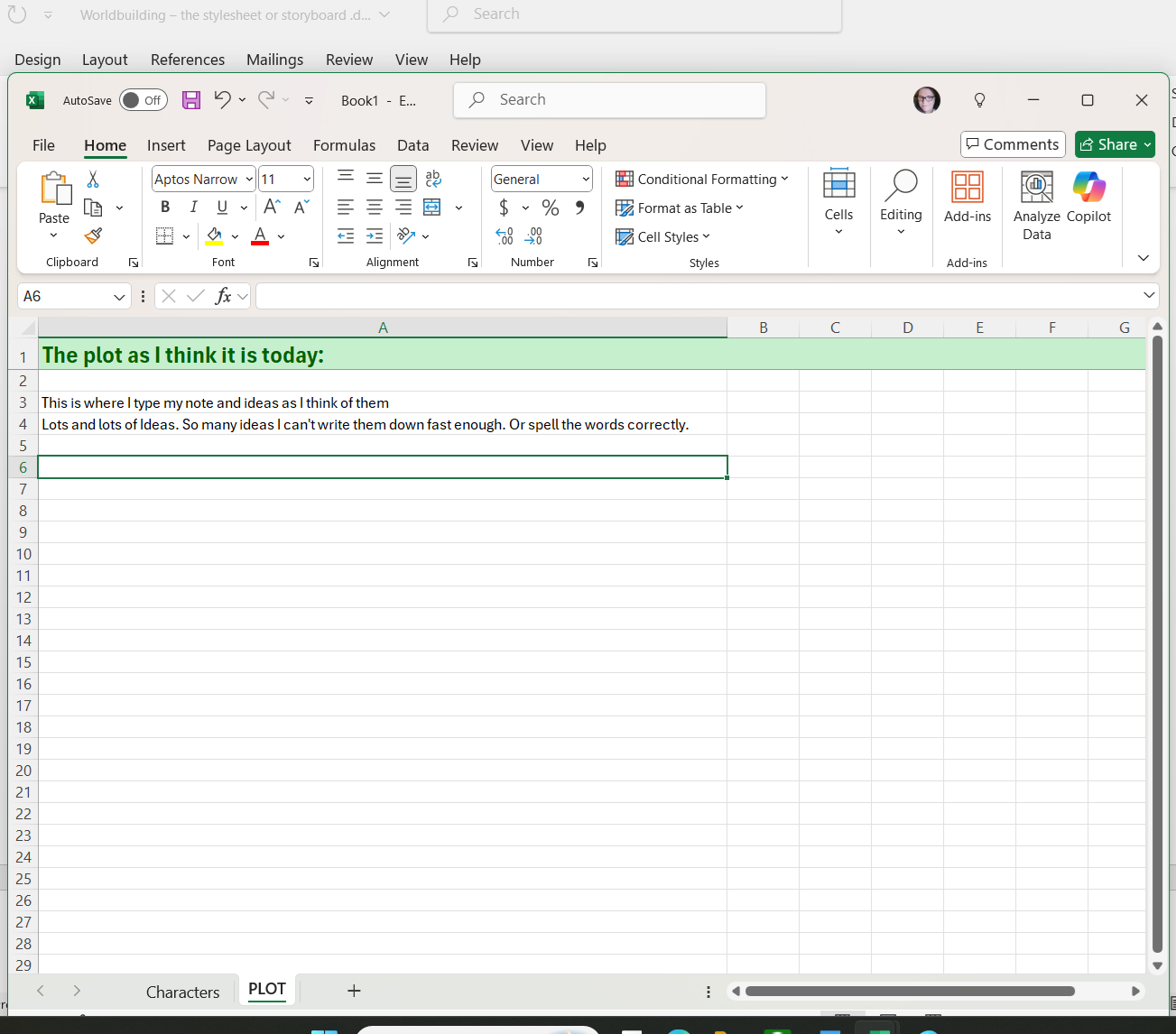

Page Two contains a brief synopsis of what I imagine the plot will be. This will be the jumping-off point for when I start writing and will change radically by the end of the process.

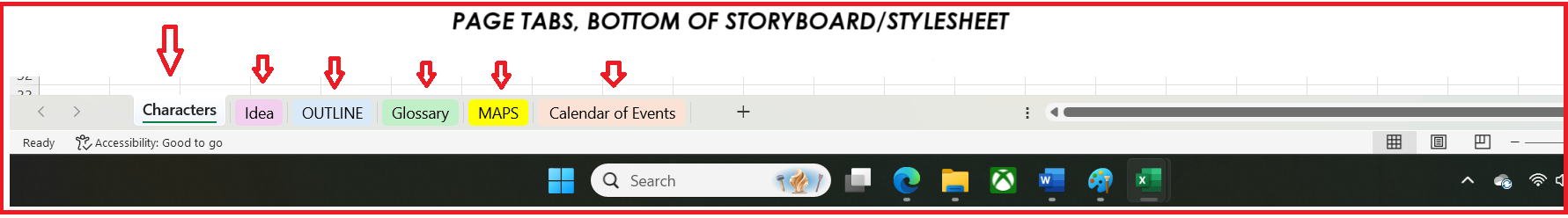

Page three of my storyboard contains An OUTLINE of events, including a prospective ending. I keep this page updated as things evolve. In every novel, a point of no return, large or small, comes into play, so I will make a note of when and where it should occur in the timeline of the plot arc.

Page four might be the GLOSSARY. This page is a list of names and invented words, which I list as they arise, all spelled the way I want them.

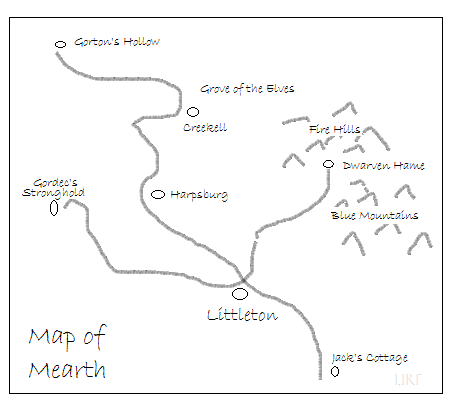

Page five will have MAPS. They don’t have to be fancy. All you need is something rudimentary to show you the layout of the world.

Page six will feature the CALENDAR of events. This is especially important, as readers despise mushy timelines.

This is how the tabs for the storyboard are labeled, allowing me to easily access what I need:

But what if your book spawns a series? The next novel should be easier to write if you kept a storyboard for book one. The storyboard will grow with each installment in that series.

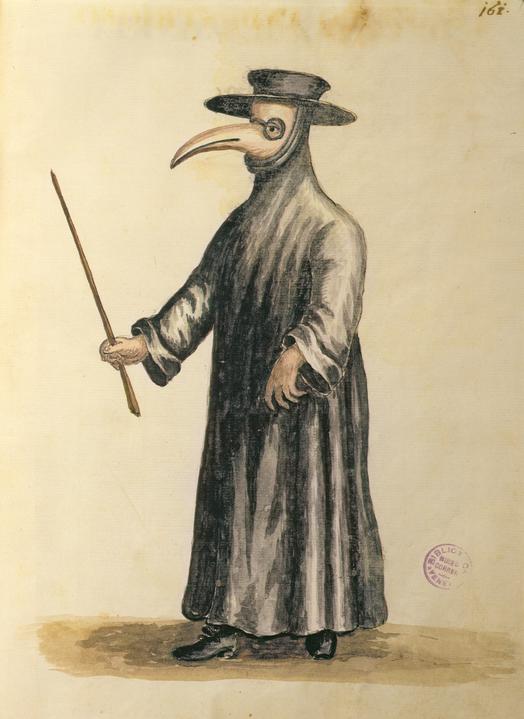

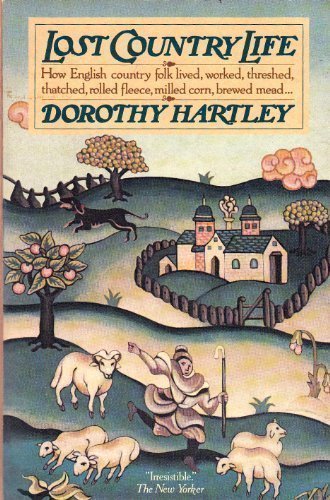

The stylesheet/storyboard is a good tool for fantasy authors because we invent entire worlds, religions, and magic systems. We don’t want to contradict ourselves or have our characters’ names change halfway through the book with no explanation.

Creating the storyboard/stylesheet helps me to know who my characters think they are in the first draft. Having an idea of their story and seeing them in their world is a good first step. Write those thoughts down so you don’t lose them. Keep writing as the ideas come to you, and soon, you’ll have the seeds of a novel.

Storyboarding plays a direct role in how a linear thinker like me works. It takes advantage of the ideas I have that might make a good story as they come to me. Those notes inspire me to begin writing the first draft and keep my imagination running.

Next week, we’ll talk about how maps and calendars are essential tools, how to make them, and why I include them in my storyboard.

Credits and Attributions

The Screenshots of the Sample Storyboard Template are my own work, © 2025 Connie J. Jasperson, All Rights Reserved.