Our post today explores my favorite Christmas story of all time, A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens.

My dear friend (and one of my favorite indie authors) Aaron Volner is an amazing narrator. Last year, he posted his incredible reading of the original manuscript of A Christmas Carol on YouTube. It is read exactly as written by Charles Dickens.

Aaron’s interpretation of this classic is spot on. He has gotten all the voices just right, from kindly Fred down to Tiny Tim.

Aaron’s interpretation of this classic is spot on. He has gotten all the voices just right, from kindly Fred down to Tiny Tim.

I think this is by far my favorite version of A Christmas Carol as it is the original manuscript and is one I will be listening to every year. The original version, as it fell out of Dicken’s pen and onto the paper, is far scarier than most modern versions, and Volner’s interpretation expresses that eeriness perfectly.

Scrooge’s horror is visceral, and his redemption is profound.

Charles Dickens would have greatly approved of this reading. I give Volner’s performance five stars—something I rarely do. You can find this wonderful reading via this link: “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens – YouTube.

It is divided into staves (chapters) so that you can listen to one a day or binge them the way I do.

Last year, Aaron’s rendition of this wonderful story prompted me to revisit a post on what modern writers can learn from Dickens, one posted several years ago.

Each time I read this tale or listen to Aaron’s narration, I learn something new about story and structure. The opening act of this tale hooks the reader and keeps them hooked. It is a masterclass in how to structure a story.

Let’s have a look at the first lines of this tale:

“Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.”

“Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.”

In that first paragraph, Dickens offers us the bait. He sinks the hook and reels in the fish (the reader) by foreshadowing the story’s first plot point–the visitation by Marley’s ghost. We want to know why Marley’s unquestionable state of decay was so crucial that the conversation between us, the readers, and Dickens, the author, was launched with that topic.

Dickens doesn’t talk down to his readers. He uses the common phrasing of his time as if he were speaking to us over tea — “dead as a doornail,” a phrase that is repeated for emphasis. This places him on our level, a friend we feel comfortable gossiping with.

He returns to the thread of Marley several pages later, with the little scene involving the doorknocker. This is where Scrooge sees the face of his late business partner superimposed over the knocker and believes he is hallucinating. This is more foreshadowing, more bait to keep us reading.

At this point, we’ve followed Scrooge through several scenes, each introducing the subplots. We have met the man who, as yet, is named only as ‘the clerk’ in the original manuscript but whom we will later know to be Bob Cratchit. We’ve also met Scrooge’s nephew, Fred, who is a pleasant, likeable man.

These subplots are critical, as Scrooge’s redemption revolves around the ultimate resolution of those two separate mini stories. He must witness the joy and love in Cratchit’s family, who are suffering but happy despite living in grinding poverty (for which Scrooge bears a responsibility).

We see that his nephew, Fred, though orphaned, has his own business to run and is well off in his own right. Fred craves a relationship with his uncle and doesn’t care what he might gain from it financially.

By the end of the first act, all the characters are in place, and the setting is solidly in the reader’s mind. We’ve seen the city, cold and dark, with danger lurking in the shadows. We’ve observed how Scrooge interacts with everyone around him, strangers and acquaintances alike.

Now we come to the first plot point in Dickens’ story arc–Marley’s visitation. This moment in a story is also called “the inciting incident,” as this is the point of no return. Here is where the set-up ends, and the story takes off.

Dickens understood how to keep a reader enthralled. No words are wasted. Every scene is important, every scene leads to the ultimate redemption of the protagonist, Ebenezer Scrooge.

This is a short tale, a novella rather than a novel. But it is a profoundly moving allegory, a parable of redemption that remains pertinent in modern society.

In this tale, Dickens asks you to recognize the plight of those whom the Industrial Revolution has displaced and driven into poverty and the obligation of society to provide for them humanely.

This is a concept our society continues to struggle with and perhaps will for a long time to come. Cities everywhere struggle with the problem of homelessness and a lack of empathy for those unable to afford decent housing. Everyone is aware of this problem, but we can’t come to an agreement for resolving it.

A Christmas Carol remains relevant even in today’s hyper-connected world. It resonates with us because of that deep, underlying call for compassion that resounds through the centuries and is, unfortunately, timeless.

As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens proves them wrong.

As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens proves them wrong.

One doesn’t have to write a novel to be an author. Whether you write blog posts, poems, short stories, novellas, or 700-page epic fantasies, you are an author. Diarists are authors. Playwrights are authors. Authors write—the act of creative writing makes one an author.

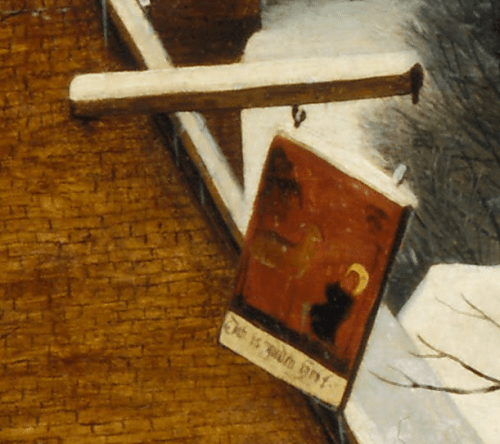

And that brings us to the featured images. The two illustrations are by John Leech from the first edition of the novella published in book form in 1843. We’re fortunate that the original art of John Leech, which Dickens himself chose to include in the book, has been uploaded to Wikimedia Commons. Thanks to the good people at Wikimedia, these prints are available for us all to enjoy.

From Wikipedia: John Leech (August 29, 1817 – October 29, 1864, in London) was a British caricaturist and illustrator. He is best known for his work for Punch, a humorous magazine for a broad middle-class audience, combining verbal and graphic political satire with light social comedy. Leech catered to contemporary prejudices, such as anti-Americanism and antisemitism, and supported acceptable social reforms. Leech’s critical yet humorous cartoons on the Crimean War help shape public attitudes toward heroism, warfare, and Britain’s role in the world. [1]

I love stories of redemption–and A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens remains one of the most beloved tales of redemption in the Western canon. Written in 1843 as a serialized novella, A Christmas Carol has inspired a landslide of adaptations in both movies and books.

Dickens was an indie, as all writers were at that time. He struggled to support his family with his writing. But we remember his works today. His great talent for storytelling gives us permission to write what we are inspired to.

May the holiday season and New Year find you and your loved ones happy and healthy, and may you have many opportunities to tell your stories.

CREDITS AND ATTRIBUTIONS:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “John Leech (caricaturist),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=John_Leech_(caricaturist)&oldid=871947694 (accessed December 25, 2022).

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Christmascarol1843 — 040.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Christmascarol1843_–_040.jpg&oldid=329166198 (accessed December 25, 2022)

A colourised edit of an engraving of Charles Dickens’ “Ghost of Christmas Present” character, by John Leech in 1843. Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Ghost of Christmas Present John Leech 1843.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Ghost_of_Christmas_Present_John_Leech_1843.jpg&oldid=329172654 (accessed December 25, 2022).

Title: La Rochelle, Charente-Maritime

Title: La Rochelle, Charente-Maritime

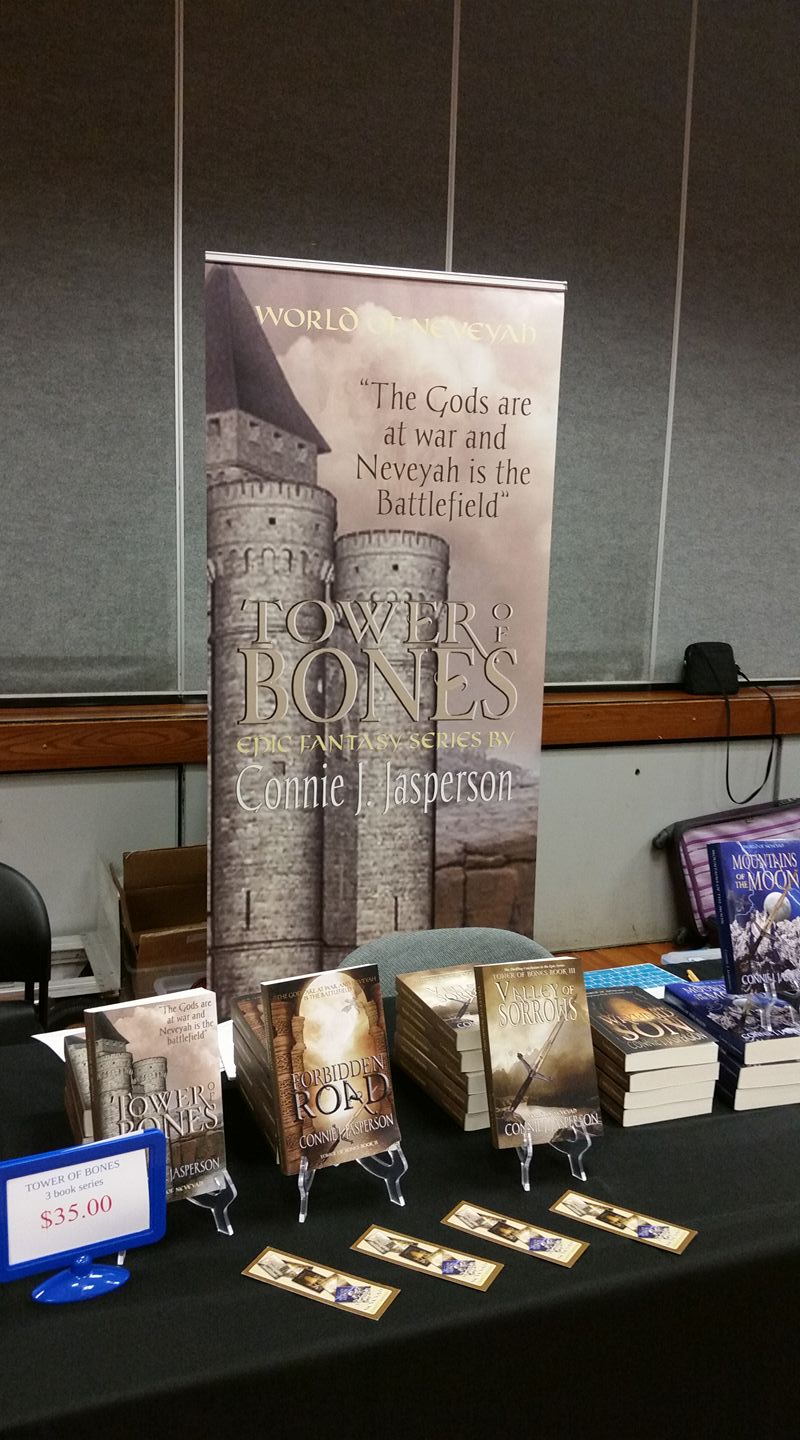

Nowadays, I am rarely able to do in-person events due to family constraints, but I used to do four events a year. However, I have some tips to help ease the path for you.

Nowadays, I am rarely able to do in-person events due to family constraints, but I used to do four events a year. However, I have some tips to help ease the path for you. The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like

The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like  Investing in some large promotional graphics, such as a retractable banner, is a good idea. A large banner is a great visual to put behind your chair. A second banner for the front of the table looks professional but requires some fiddling with pins.

Investing in some large promotional graphics, such as a retractable banner, is a good idea. A large banner is a great visual to put behind your chair. A second banner for the front of the table looks professional but requires some fiddling with pins. Make your display attractive, but I suggest you keep it simple. People will be able to see what you are selling, and the more fiddly things you add to your display, the longer setup and teardown will take. The shows and conferences I have attended offered plenty of time for this, but I’ve heard that some of the big-name conventions require you to be in or out in two hours or less.

Make your display attractive, but I suggest you keep it simple. People will be able to see what you are selling, and the more fiddly things you add to your display, the longer setup and teardown will take. The shows and conferences I have attended offered plenty of time for this, but I’ve heard that some of the big-name conventions require you to be in or out in two hours or less.

Aaron’s interpretation of this classic is spot on. He has gotten all the voices just right, from kindly Fred down to Tiny Tim.

Aaron’s interpretation of this classic is spot on. He has gotten all the voices just right, from kindly Fred down to Tiny Tim. “Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.”

“Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.” As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens proves them wrong.

As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens proves them wrong. Artist: Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530–1569)

Artist: Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530–1569)

But they are indistinct and far away, shown in a fantastic, mountainous landscape rather than the flat terrain of the Netherlands. It is almost as if they are visions of what winter could be if only the harvest had been good rather than the truth of the lone fox, hounds with empty bellies, a bankrupt tavern, and the rabbit that got away.

But they are indistinct and far away, shown in a fantastic, mountainous landscape rather than the flat terrain of the Netherlands. It is almost as if they are visions of what winter could be if only the harvest had been good rather than the truth of the lone fox, hounds with empty bellies, a bankrupt tavern, and the rabbit that got away. Directors will tell you they focus the scenery (set dressing) so it frames the action. The composition of props in that scene is finely focused world-building, and it draws the viewer’s attention to the subtext the director wants to convey.

Directors will tell you they focus the scenery (set dressing) so it frames the action. The composition of props in that scene is finely focused world-building, and it draws the viewer’s attention to the subtext the director wants to convey. As I work my way through revisions, I struggle to find the right set dressing to underscore the drama. Each item mentioned in the scene must emphasize the characters’ moods and the overall atmosphere of that part of the story.

As I work my way through revisions, I struggle to find the right set dressing to underscore the drama. Each item mentioned in the scene must emphasize the characters’ moods and the overall atmosphere of that part of the story. We can bookend the event with “doorway” scenes. These scenes determine the narrative’s pacing, which is created by the rise and fall of action.

We can bookend the event with “doorway” scenes. These scenes determine the narrative’s pacing, which is created by the rise and fall of action. The opening paragraph of a chapter and the ending paragraph are miniature scenes that bookend the central action scene. They are doors that lead us into the event and guide us on to the next hurdle the character must overcome.

The opening paragraph of a chapter and the ending paragraph are miniature scenes that bookend the central action scene. They are doors that lead us into the event and guide us on to the next hurdle the character must overcome. When the next chapter opens, he steps into an opening paragraph that leads into the next action sequence. We find out who and what new misery is waiting for him on the other side of that door.

When the next chapter opens, he steps into an opening paragraph that leads into the next action sequence. We find out who and what new misery is waiting for him on the other side of that door. When you begin making revisions, take a look at the opening paragraph of each chapter. Ask yourself how it could be rewritten to convey information and lead the reader into the action. Then, look at the final paragraph and ask yourself the same question.

When you begin making revisions, take a look at the opening paragraph of each chapter. Ask yourself how it could be rewritten to convey information and lead the reader into the action. Then, look at the final paragraph and ask yourself the same question. Title: Selling Christmas Trees

Title: Selling Christmas Trees These transitions are often small moments of conversation, italicized thoughts (internal dialogues), or contemplations written as free indirect speech. These moments are a form of action that can work well when a hard break, such as a new chapter, doesn’t feel right. The reader and the characters receive information simultaneously, but only when they need it.

These transitions are often small moments of conversation, italicized thoughts (internal dialogues), or contemplations written as free indirect speech. These moments are a form of action that can work well when a hard break, such as a new chapter, doesn’t feel right. The reader and the characters receive information simultaneously, but only when they need it. A character’s personal mood can be shown in many ways. A moment of

A character’s personal mood can be shown in many ways. A moment of  Trim that back to

Trim that back to  The main thing to watch for when employing indirect speech in a scene is to stay only in one person’s head. You can show different characters’ internal workings, provided you have a hard scene or chapter break between each character’s dialogue.

The main thing to watch for when employing indirect speech in a scene is to stay only in one person’s head. You can show different characters’ internal workings, provided you have a hard scene or chapter break between each character’s dialogue.