Artist: Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

Title: After the Hurricane

Date: 1899

Medium: Transparent watercolor, with touches of opaque watercolor, rewetting, blotting and scraping, over graphite, on moderately thick, moderately textured (twill texture on verso), ivory wove paper.

Dimensions: Height: 38 cm (14.9 in); Width: 54.3 cm (21.3 in)

Inscriptions: Signature and date bottom left: Homer 99

Current Location: Art Institute of Chicago, not on view

October 2024 has been a terrible month for the East Coast of the US. Two intense hurricanes swept up from the tropics, devastating the southern coastal region and bringing flooding inland.

The swath of death and destruction wrought by these storms is hard to describe. For those who lived through them but lost everything, life will always be defined in terms of “before the hurricane” and “after.”

In view of the deadly nature of these storms, I thought it appropriate to revisit “After the Hurricane, Bahamas” by Winslow Homer.

If you live in the US, Walmart and Kroger stores offer an option to donate a dollar or more to various hurricane relief organizations at checkout, as do many other grocery chains. Also, you can donate directly to the relief effort by going to How to help those impacted by Hurricane Helene: Charities, organizations to support relief efforts – ABC News (go.com).

About Hurricane Helene, via Wikipedia: Hurricane Helene – Wikipedia

In advance of Helene’s expected landfall, states of emergency were declared in Florida and Georgia due to the significant impacts expected, including very high storm surge along the coast and hurricane-force gusts as far inland as Atlanta. Hurricane warnings also extended further inland due to Helene’s fast motion. The storm caused catastrophic rainfall-triggered flooding, particularly in western North Carolina, East Tennessee, and southwestern Virginia, and spawned numerous tornadoes. As of October 12, at least 252 deaths have been attributed to the storm. [1]

About Hurricane Milton, via Wikipedia: Hurricane Milton – Wikipedia

Ahead of the hurricane, Florida declared a state of emergency in which many coastal residents were ordered to evacuate. Preparations were also undertaken in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. The hurricane spawned a deadly tornado outbreak and caused widespread flooding in Florida. As of October 14, 2024, Hurricane Milton killed at least 28 people: 25 in the United States and three in Mexico. Preliminary damage estimates place the total cost of destruction from the storm at over US $30 billion. [2]

What I love about this painting:

After the Hurricane, Bahamas is a watercolor painting by the American artist, Winslow Homer. It shows a man washed up on the beach after a storm, surrounded by the fragments of his shattered boat. The wreckage of the boat gives evidence of the severity of the powerful hurricane, which is retreating. Black clouds still billow but recede into the distance, and sunlight has begun to filter through the clouds.

The man may have lost his boat, but he has survived.

I love the way the whitecaps are depicted, and the colors of the sea are true to the way the ocean looks after a severe storm. Winslow Homer’s watercolor seascapes are especially intriguing to me as they are extremely dramatic and forceful expressions of nature’s power. The beauty and intensity of Homer’s vision of “ocean” are unmatched—in my opinion his seascapes are alive in a way few other artists can match.

This painting was done in 1899 and marked the end of Homer’s watercolor series depicting man against nature. That series was begun with Shark Fishing in 1885, the year he first visited the Caribbean and is comprised of at least six known paintings. The most famous of these watercolor paintings is The Gulf Stream, which was also painted in 1899. After the Hurricane, Bahamas is the last of the series.

About the artist, via Wikipedia

Winslow Homer (February 24, 1836 – September 29, 1910) was an American landscape painter and printmaker, best known for his marine subjects. He is considered one of the foremost painters in 19th-century America and a preeminent figure in American art.

Homer started painting with watercolors on a regular basis in 1873 during a summer stay in Gloucester, Massachusetts. From the beginning, his technique was natural, fluid and confident, demonstrating his innate talent for a difficult medium. His impact would be revolutionary. [3]

Credits and Attributions:

After the Hurricane, Bahamas by Winslow Homer, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Hurricane Helene,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hurricane_Helene&oldid=1251667279 (accessed October 17, 2024).

[2] Wikipedia contributors, “Hurricane Milton,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hurricane_Milton&oldid=1251634007 (accessed October 17, 2024).

[3] Wikipedia contributors, “Winslow Homer,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Winslow_Homer&oldid=1055649094 (accessed December 9, 2021).

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Winslow Homer – After the Hurricane, Bahamas.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Winslow_Homer_-_After_the_Hurricane,_Bahamas.jpg&oldid=428549979 (accessed December 9, 2021).

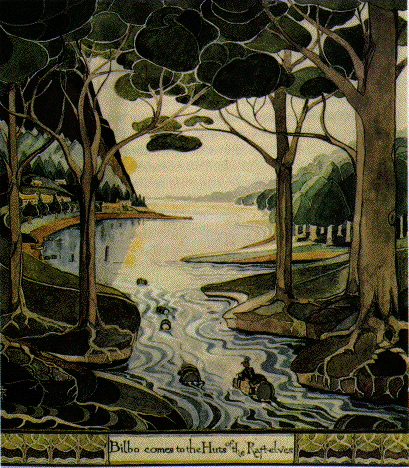

I like to sit somewhere quiet and let my mind wander, picturing the place where the opening scene takes place.

I like to sit somewhere quiet and let my mind wander, picturing the place where the opening scene takes place. The novel I intend to finish this year is set at the end of the first millennium, while last year’s effort was set in the second century after the cataclysm canonically known as the Sundering of the Worlds. This means the world is very different. The forests and wildlife have had a thousand years to rebound, and while some areas are still struggling to recover, most of the west is lush in comparison.

The novel I intend to finish this year is set at the end of the first millennium, while last year’s effort was set in the second century after the cataclysm canonically known as the Sundering of the Worlds. This means the world is very different. The forests and wildlife have had a thousand years to rebound, and while some areas are still struggling to recover, most of the west is lush in comparison. I live only sixty-five miles north of Mount St. Helens, so I have a good local example of how things look after a devastating event. I also can see how flora and fauna rebound in the years following it.

I live only sixty-five miles north of Mount St. Helens, so I have a good local example of how things look after a devastating event. I also can see how flora and fauna rebound in the years following it.  When you create a fictional world, you create a culture. As a society, the habits we develop, the gods we worship, the things we create and find beautiful, and the foods we eat are products of our culture.

When you create a fictional world, you create a culture. As a society, the habits we develop, the gods we worship, the things we create and find beautiful, and the foods we eat are products of our culture. To show a world plausibly and without contradictions, we must consider how things work, whether it takes place in a medieval world or on a space station. Don’t introduce skills and tech that can’t exist or don’t fit the era.

To show a world plausibly and without contradictions, we must consider how things work, whether it takes place in a medieval world or on a space station. Don’t introduce skills and tech that can’t exist or don’t fit the era.  For instance, blacksmiths create and repair things made of metal. The equivalent of a medieval blacksmith on a space station will have high-tech tools and a different job title. Readers notice that sort of thing.

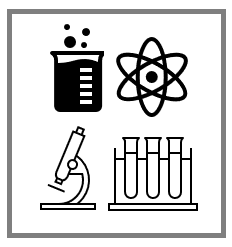

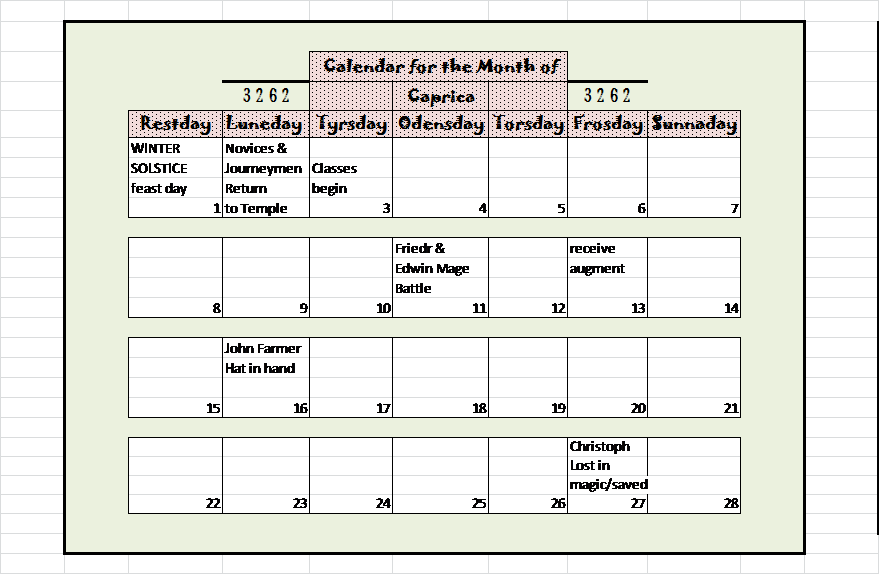

For instance, blacksmiths create and repair things made of metal. The equivalent of a medieval blacksmith on a space station will have high-tech tools and a different job title. Readers notice that sort of thing. A hand-scribbled map and a calendar of events are absolutely indispensable if your characters do any traveling. The map will help you visualize the terrain, and the calendar will keep events in a plausible order.

A hand-scribbled map and a calendar of events are absolutely indispensable if your characters do any traveling. The map will help you visualize the terrain, and the calendar will keep events in a plausible order.

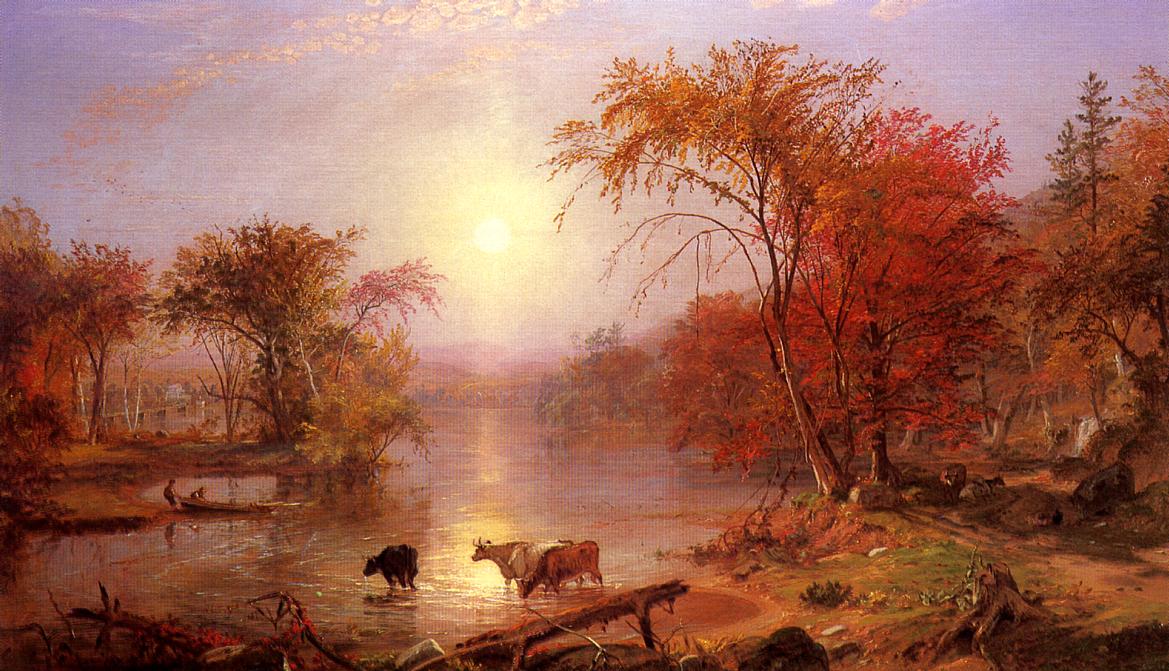

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) I was a dedicated municipal liaison for the Olympia, Washington Region for twelve years and a regular financial donor, but I walked away after the organization’s implosion last November. I will get my 50,000 new words in November but will not sign up to participate through the NaNoWriMo website.

I was a dedicated municipal liaison for the Olympia, Washington Region for twelve years and a regular financial donor, but I walked away after the organization’s implosion last November. I will get my 50,000 new words in November but will not sign up to participate through the NaNoWriMo website. Set your goal, keep a record of your daily word count or pages edited, or whatever, and let National Novel Writing Month be your month to achieve your goals. I have had buttons and stickers made as rewards for our region’s writers, and we will have write-ins as we have always done.

Set your goal, keep a record of your daily word count or pages edited, or whatever, and let National Novel Writing Month be your month to achieve your goals. I have had buttons and stickers made as rewards for our region’s writers, and we will have write-ins as we have always done.

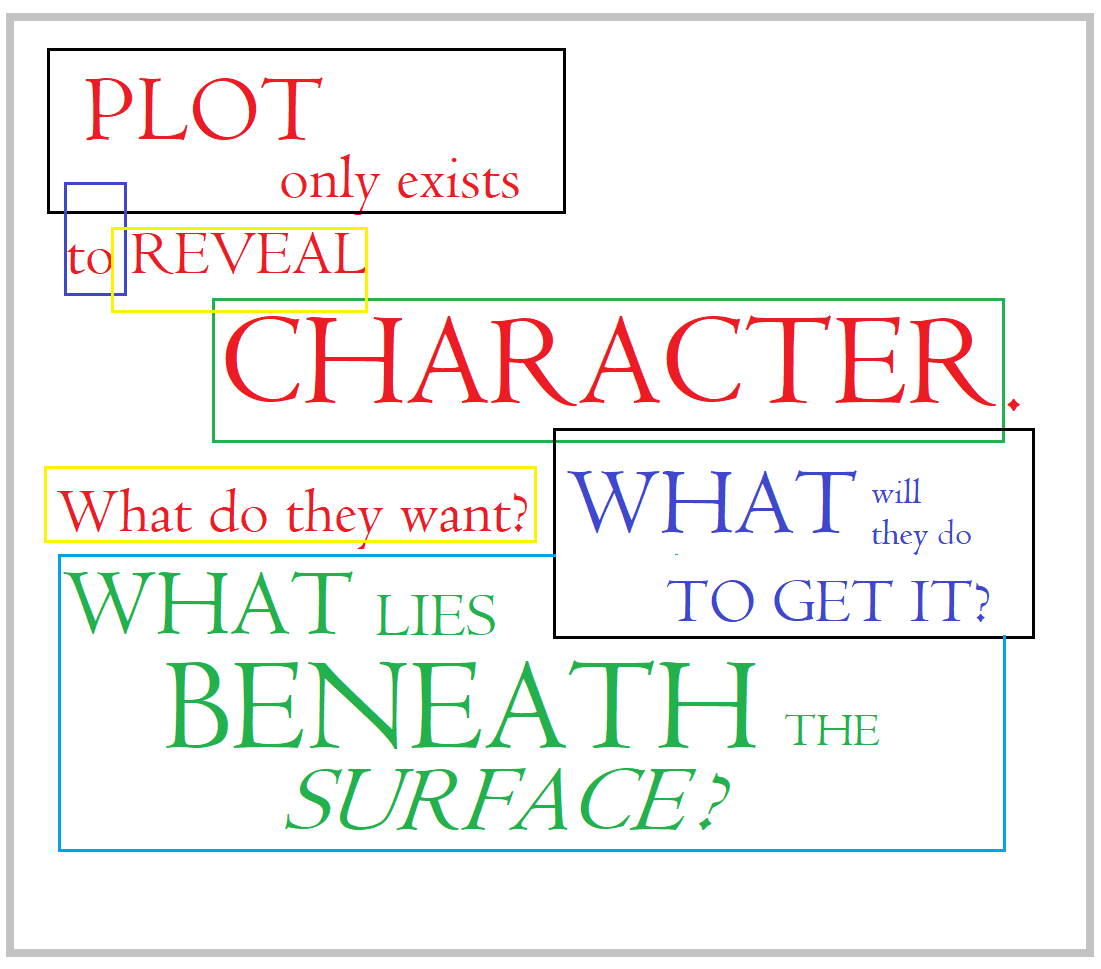

The answer to question number one kickstarts the plot: who are the players? Once I know the answer to this question, I can write, and write, and write … although most of what I write at that point will be background info. The answers to the other questions will emerge as I write the background blather.

The answer to question number one kickstarts the plot: who are the players? Once I know the answer to this question, I can write, and write, and write … although most of what I write at that point will be background info. The answers to the other questions will emerge as I write the background blather. They share some of their story the way strangers on a long bus ride might. I see the surface image they present to the world, but they keep most of their secrets close and don’t reveal all the dirt. These mysteries will be pried from them over the course of writing the narrative’s first draft.

They share some of their story the way strangers on a long bus ride might. I see the surface image they present to the world, but they keep most of their secrets close and don’t reveal all the dirt. These mysteries will be pried from them over the course of writing the narrative’s first draft. And what if you are writing poems or short stories? Graphic novels? We will also go into preparing to “speed-date your muse” when embarking on those aspects of writing.

And what if you are writing poems or short stories? Graphic novels? We will also go into preparing to “speed-date your muse” when embarking on those aspects of writing.![Falling Leaves, by Olga Wisinger-Florian, ca 1899 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/olga_wisinger-florian_-_falling_leaves.jpg?w=500)

Setting: Does the setting feel real?

Setting: Does the setting feel real? Be prepared for it to come back with some detailed critical observations, which may seem harsh. Any criticism of our life’s work feels unfair to an author who is new at this. And to be truthful, some authors never learn how to put aside their egos.

Be prepared for it to come back with some detailed critical observations, which may seem harsh. Any criticism of our life’s work feels unfair to an author who is new at this. And to be truthful, some authors never learn how to put aside their egos. Worse, perhaps they were familiar with a featured component of the story, such as medicine or police procedures. The reader might have suggested we need to do more research and then rewrite what we thought was the perfect novel.

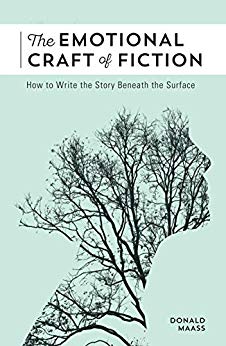

Worse, perhaps they were familiar with a featured component of the story, such as medicine or police procedures. The reader might have suggested we need to do more research and then rewrite what we thought was the perfect novel. I went out and bought books on the craft of writing, and I am still buying books on the craft today. I will never stop learning and improving.

I went out and bought books on the craft of writing, and I am still buying books on the craft today. I will never stop learning and improving. Learning the craft of writing is like learning any other trade, from cooking to carpentry. It takes work and effort to become a master.

Learning the craft of writing is like learning any other trade, from cooking to carpentry. It takes work and effort to become a master.

Title: Indian Summer by William Trost Richards

Title: Indian Summer by William Trost Richards Who is the antagonist?

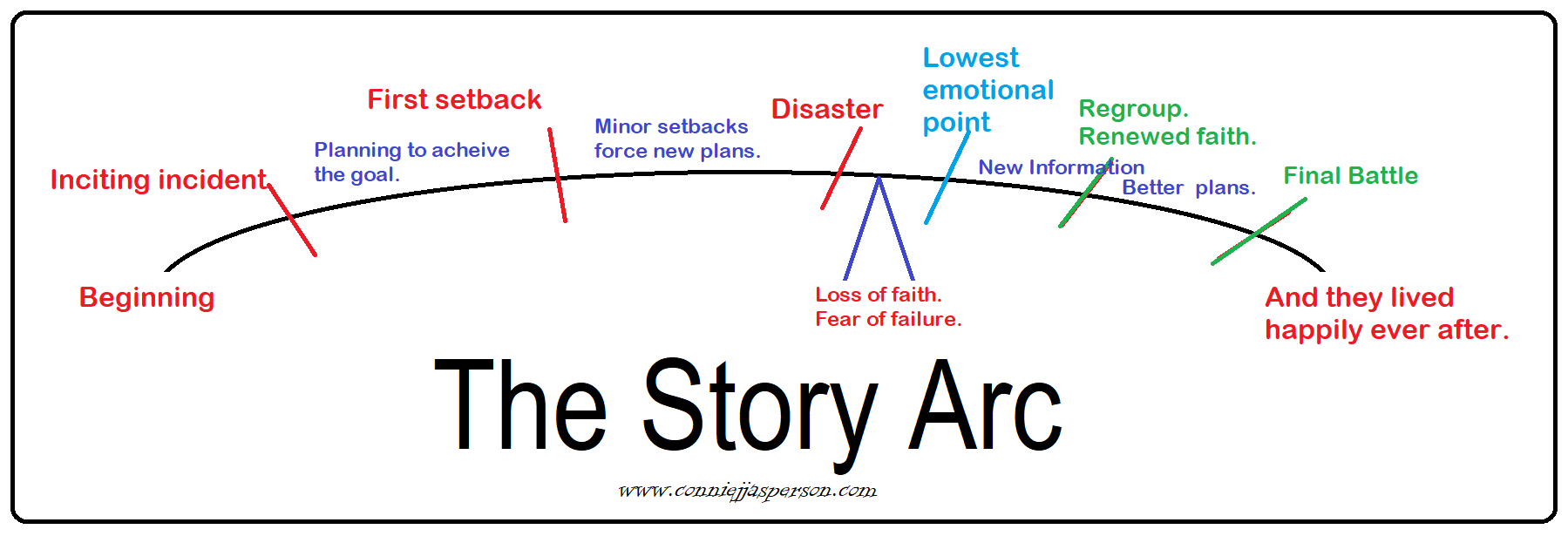

Who is the antagonist? Consider cogs: they are engineered to interlock with each other, and when they move close enough that one cog interlocks and turns another, they move other parts of the mechanism.

Consider cogs: they are engineered to interlock with each other, and when they move close enough that one cog interlocks and turns another, they move other parts of the mechanism. Each hiccup on the road to glory must tear the heroes down. Events and failures must break them emotionally and physically so that in the book’s final quarter, they can be rebuilt, stronger, and ready to face the enemy on equal terms.

Each hiccup on the road to glory must tear the heroes down. Events and failures must break them emotionally and physically so that in the book’s final quarter, they can be rebuilt, stronger, and ready to face the enemy on equal terms. Confrontations are chaotic. It’s our job to control that chaos and create a narrative with an ending that is as intense as our imaginations and logic can make it.

Confrontations are chaotic. It’s our job to control that chaos and create a narrative with an ending that is as intense as our imaginations and logic can make it. Artist:

Artist:

This happens because my characters have agency and sometimes run amok. Thus, in the second draft, I examine the freedom I give my characters to introduce their own actions and reactions within the story.

This happens because my characters have agency and sometimes run amok. Thus, in the second draft, I examine the freedom I give my characters to introduce their own actions and reactions within the story.

When the writing commences, the characters make choices and say things that surprise me. They can do this because I allow them agency.

When the writing commences, the characters make choices and say things that surprise me. They can do this because I allow them agency.

Fortunately, they are rescued by Gandalf. While he is hiding, Bilbo discovers several historically important weapons. One of them is Sting, a blade that fits Bilbo perfectly as a sword. This is a positive consequence, as the blade is crucial to Bilbo’s story and later to Frodo’s story.

Fortunately, they are rescued by Gandalf. While he is hiding, Bilbo discovers several historically important weapons. One of them is Sting, a blade that fits Bilbo perfectly as a sword. This is a positive consequence, as the blade is crucial to Bilbo’s story and later to Frodo’s story.