One of my three works-in-progress is a murder mystery set in one of my established fantasy worlds. I am currently writing the antagonist’s story and meshing each event with the protagonist’s timeline via the calendar.

My antagonist is a woman whom we’ll call Bad Grandma for the sake of this post. She takes what she wants and damn the consequences.

My antagonist is a woman whom we’ll call Bad Grandma for the sake of this post. She takes what she wants and damn the consequences.

I see Bad Grandma as a pirate in the truest sense of the word. I’m writing her as having a career marked by violence and brutality. She is definitely not a Jack Sparrow sort of pirate.

I’m at the midpoint of the first draft of this story and can’t go any further on my protagonist’s thread. Bad Grandma’s story has to be written, including the end. Then, I can return to my protagonist and write the scenes connecting the dots.

This woman has no conscience or moral boundaries, which makes writing her exhausting.

I’m a Good Grandma—I only murder people on paper. So, between bursts of writing this evil woman’s story, I find myself cleaning and cooking, activities that help me organize my thoughts.

Cooking has become a primary activity for me. The weather here at Casa del Jasperson has been cold, with a layer of frigid, applied to the general iciness of the Arctic blast. As I write this post, it is a warm and balmy 18 degrees (minus 8 Celsius). It is clear and sunny, and the thin layer of snow that fell four days ago, less than an inch, is still there.

Cooking has become a primary activity for me. The weather here at Casa del Jasperson has been cold, with a layer of frigid, applied to the general iciness of the Arctic blast. As I write this post, it is a warm and balmy 18 degrees (minus 8 Celsius). It is clear and sunny, and the thin layer of snow that fell four days ago, less than an inch, is still there.

I have been making soups in my crockpot and baking all sorts of tasty delights. After all, making and serving good food is my love language. With that said, I’m a lazy chef. I rarely cook on the stovetop, so nearly everything I serve comes from the crockpot or the oven.

I made bread nearly every day for most of my adult life because it was cheaper to make than to buy, and it tasted better. But now that it’s only Greg and I, we buy it as often as we bake it.

I’ve turned laziness into a fine art. I love my bread machine because it takes the work out of making the dough. However, I rarely bake my bread in the machine. It makes too large a loaf, and the crust can be a bit too crunchy.

I’ve turned laziness into a fine art. I love my bread machine because it takes the work out of making the dough. However, I rarely bake my bread in the machine. It makes too large a loaf, and the crust can be a bit too crunchy.

Instead, I use the “dough” setting. Once the machine says the dough is made, I divide it in half and place it in prepared loaf pans. Sometimes, I make cinnamon rolls or cranberry walnut loaves once the machine has finished its part of the process. When the finished product emerges from the oven, it has the right texture and the house smells divine.

So, let’s get back to the murdering murderer. Our story is set in a riverport town. Bad Grandma is a drug smuggler who has murdered a mage, a Temple armsmaster. With the head peacekeeper in that town dead, she escapes justice for the moment, heading downriver. She stops in another port town two days later and is arrested the moment she steps off her stolen barge.

The constable in that town is unaware that Bad Grandma has murdered a mage but knows she’s wanted for smuggling and other crimes. However, our Bad Grandma is slippery and escapes the noose by murdering the constable.

The constable in that town is unaware that Bad Grandma has murdered a mage but knows she’s wanted for smuggling and other crimes. However, our Bad Grandma is slippery and escapes the noose by murdering the constable.

She decides to sneak back home to her long-abandoned family until things cool down, believing she has them cowed enough that they’ll hide her. But she’s been so abusive all their lives that her son throws her out and alerts the city watch that she’s back in town.

So now Bad Grandma is on the road, trying to escape justice. The only avenue of escape for her is a trail through the mountains. That road takes her back to the place where she had murdered the mage.

At this point in my writing process, I need to know what Bad Grandma is doing because my protagonist, the mage who is investigating the murders, has to respond to her actions and plan how to catch her. I am writing the scenes that she is featured in, and soon, I will have the ending of the novel written. Bad Grandma’s meeting with karma resolves the central problem in this tale of woe. Once I have that solved, winding up the other threads will be easy to write.

At this point in my writing process, I need to know what Bad Grandma is doing because my protagonist, the mage who is investigating the murders, has to respond to her actions and plan how to catch her. I am writing the scenes that she is featured in, and soon, I will have the ending of the novel written. Bad Grandma’s meeting with karma resolves the central problem in this tale of woe. Once I have that solved, winding up the other threads will be easy to write.

Or so I hope!

Artist: Ivan Aivazovsky (baptized Hovhannes Aivazovsky) (1817 – 1900)

Artist: Ivan Aivazovsky (baptized Hovhannes Aivazovsky) (1817 – 1900) When we write about mild reactions, wasting words on too much description is unnecessary because mild is boring. But if you want to emphasize the chemistry between two characters, good or bad, strong gut reactions on the part of your protagonist are a good way to do so.

When we write about mild reactions, wasting words on too much description is unnecessary because mild is boring. But if you want to emphasize the chemistry between two characters, good or bad, strong gut reactions on the part of your protagonist are a good way to do so. The novel was inspired by a youthful romance Fitzgerald had with

The novel was inspired by a youthful romance Fitzgerald had with  Fitzgerald shows us Nick’s emotions, AND we see his view of everyone else’s emotions. We see their physical reactions through his eyes and through visual cues and conversations.

Fitzgerald shows us Nick’s emotions, AND we see his view of everyone else’s emotions. We see their physical reactions through his eyes and through visual cues and conversations. If you have no idea how to begin showing the basic emotions of your characters, a good handbook that offers a jumping-off point is

If you have no idea how to begin showing the basic emotions of your characters, a good handbook that offers a jumping-off point is  Students taking college-level classes in literature and English are often required to read The Great Gatsby and other classic novels from that era, such as

Students taking college-level classes in literature and English are often required to read The Great Gatsby and other classic novels from that era, such as  After we survive the middle crisis, we have falling action. We receive the crucial information, the characters regroup, and we experience the unfolding of events leading to the conclusion. The protagonist’s problems are resolved, and we (the readers) are offered a good ending and closure.

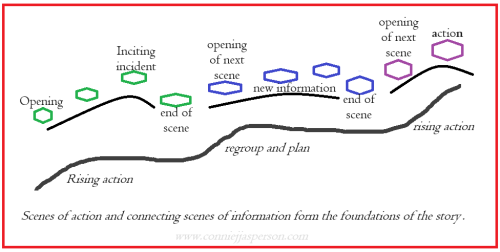

After we survive the middle crisis, we have falling action. We receive the crucial information, the characters regroup, and we experience the unfolding of events leading to the conclusion. The protagonist’s problems are resolved, and we (the readers) are offered a good ending and closure. These small arcs of action, reaction, and calm push the plot and ensure it doesn’t stall. Each scene is an opportunity to ratchet up the tension and increase the overall conflict that drives the story.

These small arcs of action, reaction, and calm push the plot and ensure it doesn’t stall. Each scene is an opportunity to ratchet up the tension and increase the overall conflict that drives the story. Transition scenes must also have an arc supporting the cathedral that is our novel. They will begin, rise to a peak as the necessary information is discussed, and ebb when the characters move on.

Transition scenes must also have an arc supporting the cathedral that is our novel. They will begin, rise to a peak as the necessary information is discussed, and ebb when the characters move on. Plots are driven by an imbalance of power. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information.

Plots are driven by an imbalance of power. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information. When we write a story, no matter the length, we hope the narrative will keep our readers interested until the end of the book. We lure readers into the scene and reward them with a tiny dose of new information.

When we write a story, no matter the length, we hope the narrative will keep our readers interested until the end of the book. We lure readers into the scene and reward them with a tiny dose of new information.![Attribution: John Singer Sargent [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/sargent_-_paul_helleu_sketching_with_his_wife.jpg?w=500&h=412)

If you have been a computer user for any length of time, you know that hardware failure, virus attacks by hackers, and other computer disasters will happen. They’re like the

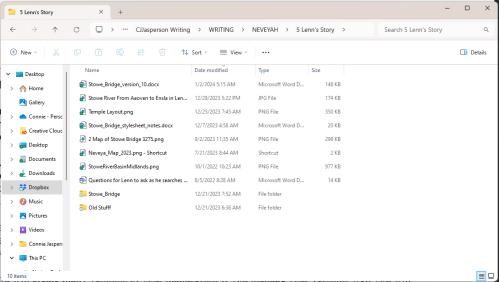

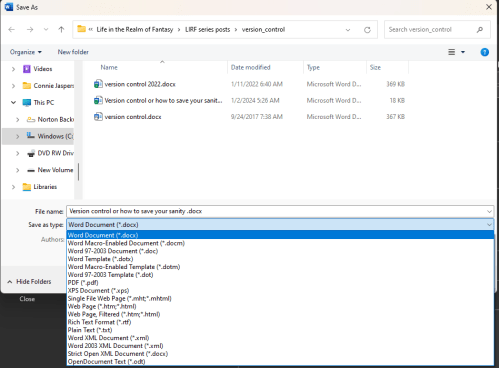

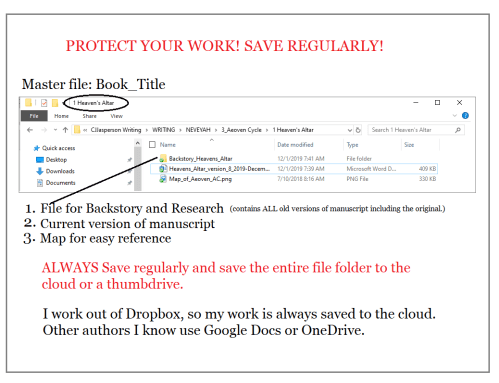

If you have been a computer user for any length of time, you know that hardware failure, virus attacks by hackers, and other computer disasters will happen. They’re like the  This year, I met a young man who, being new to using a word processing program, forgot how he named his 2022 manuscript. He couldn’t find it when he decided to start writing again. I showed him how to search for files by date, taught him how to name documents, and taught him how to create a master file for all the files generated in the process of writing his book.

This year, I met a young man who, being new to using a word processing program, forgot how he named his 2022 manuscript. He couldn’t find it when he decided to start writing again. I showed him how to search for files by date, taught him how to name documents, and taught him how to create a master file for all the files generated in the process of writing his book. I work out of Dropbox, so when I save and close a document, my work is automatically saved and backed up to

I work out of Dropbox, so when I save and close a document, my work is automatically saved and backed up to  One thing I hear from new writers is how surprised they are at how easily something that should be simple can veer out of control. The worst thing that can happen to an author is accidentally saving an old file over the top of your new file or deleting the file entirely.

One thing I hear from new writers is how surprised they are at how easily something that should be simple can veer out of control. The worst thing that can happen to an author is accidentally saving an old file over the top of your new file or deleting the file entirely. I make a separate subfolder for my work when it’s in the editing process. That subfolder contains two subfolders, and one is for the chapters my editor sends me in their raw state with all her comments:

I make a separate subfolder for my work when it’s in the editing process. That subfolder contains two subfolders, and one is for the chapters my editor sends me in their raw state with all her comments:

We are at the same latitude as Paris, Zurich, and Montreal but usually get a lot more rain than those cities. The North Pacific can be wild at this time of the year, which makes for some great storm-watching.

We are at the same latitude as Paris, Zurich, and Montreal but usually get a lot more rain than those cities. The North Pacific can be wild at this time of the year, which makes for some great storm-watching. By the time the authors got to the meat of the matter (which was late in the second half) I no longer cared. Truthfully, when the fluff is carved away from this book, you might have 20,000 or so words of an interesting story—a novella.

By the time the authors got to the meat of the matter (which was late in the second half) I no longer cared. Truthfully, when the fluff is carved away from this book, you might have 20,000 or so words of an interesting story—a novella. I’m planning two volumes because one will feature stories set in the world of Neveyah, and the other will be random speculative short fiction pieces.

I’m planning two volumes because one will feature stories set in the world of Neveyah, and the other will be random speculative short fiction pieces.

I have talked about this novella many times, as I consider it one of the most enduring stories in Western literature. The opening act of this tale is a masterclass in how to structure a story.

I have talked about this novella many times, as I consider it one of the most enduring stories in Western literature. The opening act of this tale is a masterclass in how to structure a story. “Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.”

“Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.” As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens says differently.

As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens says differently.