Tomorrow is the final day of NaNoWriMo 2023. I have just over 60,000 words written on my current novel. We’ve had some gloomy days here. Fog set in on Sunday, enveloping the world (at least the world I could see from my window); as I write this, it still hasn’t lifted. To enhance the gloomy ambiance, I play my favorite writing music, Final Fantasy Guitar Collection, Vol. 2 | John Oeth – YouTube, and write dark scenes about shady people doing evil deeds.

When I can’t write anymore, I eat chocolate and read trashy romance novels about vampires.

When I can’t write anymore, I eat chocolate and read trashy romance novels about vampires.

I’m struggling to plot the end of this novel. If I know how the story will end, I can build a plot to that point. Over the years of editing and reviewing books, I’ve assembled a list of questions that help me nudge an idea loose.

Right now, one murder has been committed, and we now know who did it. Unfortunately, the outline from the midpoint on is a bit too concise:

“Karras follows Rahlie, murders him. Also attacks and robs Lorris, who survives. Lenn and Salyan hunt the killer. Fight, Lenn wounded, they prevail. Salyan kills Karras. Or maybe Lenn does.”

That’s it.

It isn’t a lot to go on.

I need to spend several days visualizing the goal, picturing each event, and mind-wandering on paper until I have concrete scenes. I need to write a few paragraphs that will become the final chapters.

I need to spend several days visualizing the goal, picturing each event, and mind-wandering on paper until I have concrete scenes. I need to write a few paragraphs that will become the final chapters.

I will write a synopsis of the final events as if I had witnessed them from the sidelines. It’s a good way to visualize what happened and will give me something to expand on over the final 25,000 words. I will have scenes firmly in mind and be able to write them from Lenn’s point of view.

So now, I’m outlining again, and it will become my synopsis. I have my character notes detailing what they wanted initially.

And, no matter their failings, our protagonist is endowed with an extraordinary power not granted to ordinary mortals: plot armor. They alone are allowed to survive all manner of grievous wounds and deadly encounters because they are needed for the plot to continue.

I ask myself several questions, and the answers show me at a glance how my characters have been changed by the events they have experienced.

- What do the characters want now?

- What will they have to sacrifice next?

- What stands in the way of their achieving the goal?

- Do they get what they initially wanted, or have their desires evolved away from that goal?

My heroes and villains all see themselves as the stars and winners in this fantasy rumble. They intend to prevail at any cost. What is the final hurdle, and what will they lose in the process? Is the price physical suffering or emotional? Or both?

My heroes and villains all see themselves as the stars and winners in this fantasy rumble. They intend to prevail at any cost. What is the final hurdle, and what will they lose in the process? Is the price physical suffering or emotional? Or both?

What happens when they catch up with Karras?

Sometimes, neither party knows what they will do once they achieve their goal, as they haven’t thought that far ahead. They (and I, as the author) have been completely focused on getting to this point in the story.

So here we are, just after the midpoint crisis. A serious incident occurred, launching the third act and setting my protagonists on the hunt. Now, something worse must occur that makes them fear they won’t achieve their objectives after all. My protagonists must get creative and work hard to accomplish their desired goal. They must overcome their own doubts and make themselves stronger.

I also need to insert several scenes showing what the enemy knows that the protagonists do not. I need to discover more about her motives and what she is capable of.

My mental rambling is accomplishing something. My characters are all getting their acts together. They are finding ways to resolve the conflict and are ready to commence the fourth act, where they will embark on the final battle.

My mental rambling is accomplishing something. My characters are all getting their acts together. They are finding ways to resolve the conflict and are ready to commence the fourth act, where they will embark on the final battle.

I know they will face off with weapons. I don’t know where that will happen, so that is something I need to work out.

By the end of the book, all the threads will have been drawn together and resolved for better or worse. The ending must be finite and wrap up the conflict.

Everyone goes home to their families and lives happily. In real life, people live happily, but no one really lives deliriously happily ever after.

That’s another story and a different genre.

Thank you all for listening to my mental ramblings—I hope they help you. Now, I can write a few paragraphs and give myself a skeleton to hang the story on with dots to connect and finish this first draft.

I still had no idea there was a wider community of writers in my area, and even if I had, I wouldn’t have felt worthy of gate-crashing one of their meetings.

I still had no idea there was a wider community of writers in my area, and even if I had, I wouldn’t have felt worthy of gate-crashing one of their meetings. The next book I bought was in 2002:

The next book I bought was in 2002:  Finishing off the resources from the official NaNoWriMo store is Grant Falkner’s handbook,

Finishing off the resources from the official NaNoWriMo store is Grant Falkner’s handbook,  Damn Fine Story

Damn Fine Story Many local libraries offer a service where one can submit a question and have it answered by email. If that isn’t an option and we’re feeling ambitious, you can check out eBooks on any subject.

Many local libraries offer a service where one can submit a question and have it answered by email. If that isn’t an option and we’re feeling ambitious, you can check out eBooks on any subject. Here is a link to the great Neil Gaiman’s absolutely wonderful, infinitely comforting, yet utterly challenging advice for writers:

Here is a link to the great Neil Gaiman’s absolutely wonderful, infinitely comforting, yet utterly challenging advice for writers:  In 2010, I gained a wonderful local group through attending write-ins for NaNoWriMo. Nowadays, we meet weekly via Zoom, as some members are now living far away from Olympia. My fellow writers are a never-ending source of support and information about both the craft and the industry. We write in various genres and gladly help each other bring new books into the world. But more than that, we are good, close friends.

In 2010, I gained a wonderful local group through attending write-ins for NaNoWriMo. Nowadays, we meet weekly via Zoom, as some members are now living far away from Olympia. My fellow writers are a never-ending source of support and information about both the craft and the industry. We write in various genres and gladly help each other bring new books into the world. But more than that, we are good, close friends.![Peasant Wedding by David Teniers the Younger [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/david_teniers_de_jonge_-_peasant_wedding_1650.jpg?w=500)

Narrative essays are drawn directly from real life, but they are fictionalized accounts. They detail an incident or event and talk about how the experience affected the author on a personal level.

Narrative essays are drawn directly from real life, but they are fictionalized accounts. They detail an incident or event and talk about how the experience affected the author on a personal level. Wallace went to the fair thinking it would be a boring event featuring farm animals, which might be beneath him. But it was his first official assignment for Harpers, and he didn’t want to screw it up. What he found there, the people he met, their various crafts, and how they loved their lives profoundly affected him, altering his view of himself and his values.

Wallace went to the fair thinking it would be a boring event featuring farm animals, which might be beneath him. But it was his first official assignment for Harpers, and he didn’t want to screw it up. What he found there, the people he met, their various crafts, and how they loved their lives profoundly affected him, altering his view of himself and his values. Literary magazines want well-written essays on a wide range of topics and life experiences presented with a fresh point of view. Some publications will pay well for first rights.

Literary magazines want well-written essays on a wide range of topics and life experiences presented with a fresh point of view. Some publications will pay well for first rights. Don’t be afraid to write with a wide vocabulary, as people who read these publications have a broad command of language.

Don’t be afraid to write with a wide vocabulary, as people who read these publications have a broad command of language. If the editor wants changes, they will make clear what they want you to do. Editors know what their intended audience wants. Trust that the editor knows their business.

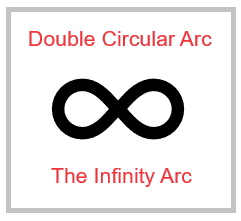

If the editor wants changes, they will make clear what they want you to do. Editors know what their intended audience wants. Trust that the editor knows their business. Knowing my intended word count helps me create a story, from drabbles to novels. For me, it works in stories with a traditional arc as well as those with a circular arc.

Knowing my intended word count helps me create a story, from drabbles to novels. For me, it works in stories with a traditional arc as well as those with a circular arc. In a circular narrative, the story begins at point A, takes the protagonist through life-changing events, and brings them home, ending where it started. The starting and ending points are the same, and the characters return home, but they are fundamentally changed by the story’s events.

In a circular narrative, the story begins at point A, takes the protagonist through life-changing events, and brings them home, ending where it started. The starting and ending points are the same, and the characters return home, but they are fundamentally changed by the story’s events. At this point, our first protagonist knows that he must resolve the problem and protect his people, which he does. There is more to his side of the story, of course. But this is a story with two sides. Aeddan’s point of view is not the entire story.

At this point, our first protagonist knows that he must resolve the problem and protect his people, which he does. There is more to his side of the story, of course. But this is a story with two sides. Aeddan’s point of view is not the entire story. Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating a believable atmosphere when limited to only a small word count. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I wanted to expand on the theme of dragons and use it to show two aspects of a place whose national symbol is the Red Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch).

Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating a believable atmosphere when limited to only a small word count. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I wanted to expand on the theme of dragons and use it to show two aspects of a place whose national symbol is the Red Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch). Artist: Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/1629–1682)

Artist: Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/1629–1682) We all know the best stories have an arc of rising action flowing smoothly from scene to scene. Those changes are called transitions and are little connecting scenes. Conversations and indirect speech (thoughts, ruminations, contemplations) often make good transitions when a hard break, such as a new chapter, doesn’t feel right.

We all know the best stories have an arc of rising action flowing smoothly from scene to scene. Those changes are called transitions and are little connecting scenes. Conversations and indirect speech (thoughts, ruminations, contemplations) often make good transitions when a hard break, such as a new chapter, doesn’t feel right. We know dialogue must have a purpose and move toward a conclusion of some sort. This means conversations or ruminations should provide a sense of moving the story forward. These are moments of regrouping and processing what has just occurred. Dialogue and introspection are also where the protagonist and the reader learn more about the mysterious backstory.

We know dialogue must have a purpose and move toward a conclusion of some sort. This means conversations or ruminations should provide a sense of moving the story forward. These are moments of regrouping and processing what has just occurred. Dialogue and introspection are also where the protagonist and the reader learn more about the mysterious backstory. So now that we know what must be conveyed and why, we find ourselves walking through the Minefield of Too Much Exposition.

So now that we know what must be conveyed and why, we find ourselves walking through the Minefield of Too Much Exposition. When I began writing seriously, I was in the habit of using italicized thoughts and characters talking to themselves to express what was happening inside them.

When I began writing seriously, I was in the habit of using italicized thoughts and characters talking to themselves to express what was happening inside them. If you aren’t careful, you can slip into “head-hopping,” which is incredibly confusing for the reader. First, you’re in one person’s thoughts, and then another—like watching a tennis match.

If you aren’t careful, you can slip into “head-hopping,” which is incredibly confusing for the reader. First, you’re in one person’s thoughts, and then another—like watching a tennis match. Crockpot soups are high on the menu here at Casa del Jasperson. I do most of the work for dinner in the morning and get it out of the way along with the other housework, and then I can write and whine about writing.

Crockpot soups are high on the menu here at Casa del Jasperson. I do most of the work for dinner in the morning and get it out of the way along with the other housework, and then I can write and whine about writing. The work inspired by a visual prompt often has nothing to do with the image. But it has everything to do with the nature of storytelling. The ability to explain the world through stories and allegory emerges strongly in artists of all mediums—painters, sculptors, writers, musicians, and dancers.

The work inspired by a visual prompt often has nothing to do with the image. But it has everything to do with the nature of storytelling. The ability to explain the world through stories and allegory emerges strongly in artists of all mediums—painters, sculptors, writers, musicians, and dancers. These jolly rogues have such vivid personalities that the viewer immediately feels a kinship. Who were they? Did they keep their day jobs? Or were they charming moochers living off the kindness of friends?

These jolly rogues have such vivid personalities that the viewer immediately feels a kinship. Who were they? Did they keep their day jobs? Or were they charming moochers living off the kindness of friends? And what other symbolism was incorporated in this painting that art patrons in the 17th century would know but we who view it through 21st-century eyes wouldn’t? Eelko Kappe’s article on this painting,

And what other symbolism was incorporated in this painting that art patrons in the 17th century would know but we who view it through 21st-century eyes wouldn’t? Eelko Kappe’s article on this painting,  Artist:

Artist: The well of inspiration has gone dry.

The well of inspiration has gone dry. Arcs of action drive plots. Every reader knows this, and every writer tries to incorporate that knowledge into their work. Unfortunately, when I’m tired, random, disconnected events that have no value will seem like good ideas.

Arcs of action drive plots. Every reader knows this, and every writer tries to incorporate that knowledge into their work. Unfortunately, when I’m tired, random, disconnected events that have no value will seem like good ideas. As you clarify why the protagonist must struggle to achieve their goal, the words will come.

As you clarify why the protagonist must struggle to achieve their goal, the words will come.