Artist: Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530–1569)

Artist: Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530–1569)

Title: English: Hunters in the Snow (German: Jäger im Schnee) (Winter)

Date: 1565

Medium: oil on oak wood

Dimensions: height: 1,170 mm (46.06 in); width: 1,620 mm (63.77 in)

Collection: Kunsthistorisches Museum

What I love about this painting:

This is one of Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s most famous paintings and is a favorite of mine because of the rich societal commentary Brueghel painted into this scene.

Perhaps you have seen it at some point, on a calendar or a Christmas card, and after a cursory glance, you dismissed it as a bucolic illustration of a bygone era.

You fell for his trap. Bruegel the Elder was an observer of life and had a wide streak of sarcasm that emerged in his work. He lived in a time of extreme capitalism, where the nobility and the Church made the rules, with no regard for those whose labors had made them rich.

Brueghel was a master at slipping pointed observations into the scene in such a way that they go unnoticed if one can’t be bothered to look closely.

In his day, the fortunate few who were wealthy were gloriously, impossibly rich. Money was minted by the rulers in the form of coins, and trickle-down economics didn’t work then any better than it does now. The peasants struggled to find food and shelter, going underpaid and overworked.

The middle class hung on, doing comparatively well. However, all it took for the prosperous farmer to be reduced to starvation was one bad harvest. That bad harvest toppled the small traders and crafters as well. When the middle class can’t afford new shoes or garments, tailors and cobblers suffer as well.

Critics didn’t praise his work, as it is unabashedly primitive, created for the common person’s enjoyment, and art critics don’t care much about what the common folk like. Nonetheless, his work is still highly prized by collectors.

Brueghel had a sneaky sense of humor and employed it to show the truth about humanity and inhumanity in his work.

Even now, four centuries after his era, ordinary people can relate to his work because, underneath the technological advances that we will be remembered for, things haven’t changed that much. The uber-rich are still uber-rich, and the middle class is still footing the bill.

Brueghel lived during a time of religious revolution in the Netherlands, and walking the line between both factions must have been difficult. Some have said that Bruegel (and possibly his patron) were attempting to portray an ideal of what country life used to be or what they wished it to be.

That is because they didn’t look deeper, giving it a cursory glance and moving on. On the surface and from a distance, this is a bucolic scene depicting ordinary peasants enjoying the winter. But when you look deeper, really look at it, you can see the irony of it, the honesty that Brueghel hid in plain sight.

Brueghel used symbolism to convey an entire story by employing paradox and gallows humor in every painting. Here, he shows us that winter was harsh, and for the average person, survival required a lot of work, sometimes for nothing.

He shows us the hunters returning with empty game bags, the lone corpse of a skinny fox, and little else.

One dog looks at us with starving eyes, as if hoping for scraps.

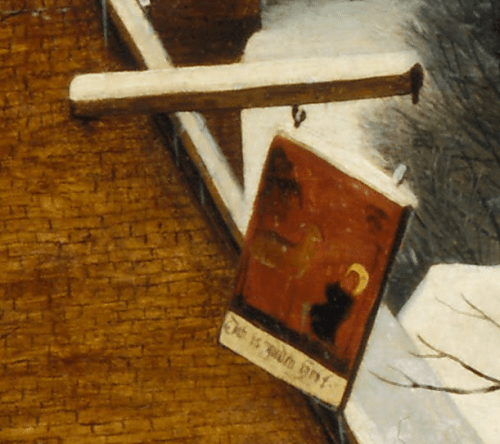

The tavern’s sign is about to fall down, a large hint that all is not well. That symbolic broken sign tells us the owners are bankrupt.

The owners are cooking outside, directly in front of the door, evicted from their home and business. A woman brings a bundle of straw out of the inn to use as fuel, while in the distance an ox-drawn wagon is heavily laden with firewood. Where is it going? Not to their inn, that is for sure.

And most intriguingly, a man is carrying a table away. He glances over his shoulder at the meager soup they are cooking, as if they had somehow gotten it away before he could take that, too. Is he the new owner, having acquired it for pennies from the city by paying the taxes at a forced bankruptcy sale? Or is he a hired thug employed by the new owner?

A rabbit has crossed the hunters’ path and evaded their snares.

Ravens, long considered birds of ill omen, roost in the trees above the inn and the hunters and fly above the revelers, a portent of worse days to come.

But in this story, Brueghel’s characters have hope and faith that things will improve. In the distance (the future) people are playing winter games.

But they are indistinct and far away, shown in a fantastic, mountainous landscape rather than the flat terrain of the Netherlands. It is almost as if they are visions of what winter could be if only the harvest had been good rather than the truth of the lone fox, hounds with empty bellies, a bankrupt tavern, and the rabbit that got away.

But they are indistinct and far away, shown in a fantastic, mountainous landscape rather than the flat terrain of the Netherlands. It is almost as if they are visions of what winter could be if only the harvest had been good rather than the truth of the lone fox, hounds with empty bellies, a bankrupt tavern, and the rabbit that got away.

About this painting, via Wikipedia, the Fount of All Knowledge:

The Hunters in the Snow (Dutch: Jagers in de Sneeuw), also known as The Return of the Hunters, is a 1565 oil-on-wood painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The Northern Renaissance work is one of a series of works, five of which still survive, that depict different times of the year. The painting is in the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria. This scene is set in the depths of winter during December/January.

The painting shows a wintry scene in which three hunters are returning from an expedition accompanied by their dogs. By appearances the outing was not successful; the hunters appear to trudge wearily, and the dogs appear downtrodden and miserable. One man carries the “meager corpse of a fox” illustrating the paucity of the hunt. In front of the hunters in the snow are the footprints of a rabbit or hare—which has escaped or been missed by the hunters. The overall visual impression is one of a calm, cold, overcast day; the colors are muted whites and grays, the trees are bare of leaves, and wood smoke hangs in the air. Several adults and a child prepare food at an inn with an outside fire. Of interest are the jagged mountain peaks which do not exist in Belgium or Holland. [1]

Credits and Attributions:

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Pieter Bruegel the Elder – Hunters in the Snow (Winter) – Google Art Project.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_Hunters_in_the_Snow_(Winter)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg&oldid=898942431 (accessed December 18, 2024).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “The Hunters in the Snow,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Hunters_in_the_Snow&oldid=1262746140 (accessed December 18, 2024).