Every society, fantasy, sci-fi, or real-world, must have an overarching political structure—a government of some sort. Humans are tribal – like all primates we are comfortable when we have a hierarchy of decision-makers to guide the tribe.

Every society, fantasy, sci-fi, or real-world, must have an overarching political structure—a government of some sort. Humans are tribal – like all primates we are comfortable when we have a hierarchy of decision-makers to guide the tribe.

A simple society might consist of an elder and several trusted advisors.

A more complex society might have a monarch leading a society composed of multiple layers:

Monarch/Royalty

→Nobility

→→Lesser Nobility

→→→Upper Middle Class

→→→→Middle Class

→→→→→Lower Middle Class

→→→→→→Lower Class

→→→→→→→Poorest Class

Every human society, large or small, is divided into layers and classes, whether we want to admit it or not. Change the word “Monarch” to “Mayor,” Governor,” “President,” “Pope,” or “Prime Minister,” and the society they lead falls into the same layers.

This is because someone is always more important, richer, has more power, makes the rules.

The politics of a society are an invisible construct that affects every aspect of a story, even if it isn’t directly addressed. Our characters have a place within that structure. When you know what that place is, you write their story accordingly. If you know your characters’ social caste, you know if they are rich or poor; hungry or well-fed. This will shape them throughout the story:

- Hunger drives conflict

- Well-fed could mean a complacent society

Every society has laws, inviolable rules. Breaking these laws has consequences.

Some small tribal societies have unwritten codes of ethics, but they are as firmly enforced as any written laws. When a character goes against the commonly accepted rules, they must face the consequences.

That flouting of civil laws is an opportunity for conflict.

Sometimes I run short of words on a new project but I can’t set it aside. At that point I go deep into the backstory and examine the hidden underpinnings of their society. Little, if any, of this backstory will enter into the finished product. But I have found that when my characters are sure of what their station in society is, I can write their journey with confidence and authority.

I need to know who they are, how they see themselves and their future, and how they fit organically into their world.

One aspect that is a hidden support structure of every fantasy society is the government. Even if it doesn’t come into the story, take a few moments to examine the political power structure of your world. It’s a good idea to write down a page or so of information detailing the political and monetary structure of the world your characters inhabit.

As I create the political power-structure, I find that the opportunities for creating tension within the story also grow. I keep a list of those ideas so that when I run short on creativity, I have a bit in the bank, so to speak.

However, in order to convey that information logically and without contradictions, you must have an idea of how things work. Does the government/legal system affect your characters? If not, this exercise is a waste of time, sorry.

Who has the power and privilege in that society, and who is the underclass?

Who has the power and privilege in that society, and who is the underclass?- How is your society divided? Who has the wealth?

- Who has the power? Men, women—or is it a society based on mutual respect? Is one race more entitled than another?

- Monarchy, Elected officials, Warlords, Shamans, or what?

- How do they get that power? Hereditary, elected, military coup?

- What laws affect your characters or hinder them?

- How are the governing people perceived? Foolish or wise? Honest or Corrupt?

- What place does religion have in this society? We examined religion last week in the post Creating Power Structures and Religions.

- What passes for morality? You only need to worry about the moral dilemmas that come into your story.

- If a character goes against society’s unwritten or moral laws, what are the consequences?

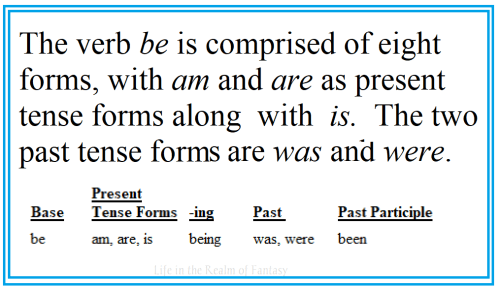

One critical aspect of society that governments have control of is money. If you have a fantasy society, design a simple monetary system. Keep it simple, so you don’t contradict yourself over the course of the story.

I use the same system in all three of my fantasy worlds. A Gold is comprised of 10 Silvers. A Silver is comprised of 10 Coppers.

In a sci-fi world, you can get away with using a blanket term like credits. These are easy concepts for a reader to imagine without your having to go into detail. Examples might be:

- Innkeeper: “A mug of ale is three coppers. No coppers, no ale.”

- Spaceport pawnbroker: “It’s unregistered. A weapon like this is worth five hundred credits, don’t you agree?”

If you’re writing in a speculative fiction world and you absolutely must use created names for money and positions, make those words simple to read and pronounce, and once you have established them, don’t deviate from them.

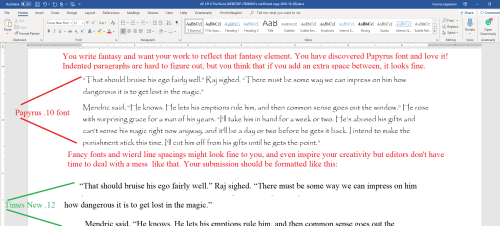

Good world building takes the familiar and shapes it into unfamiliar ways. It’s only my opinion, but I suggest you keep to familiar terms for leaders. King/queen, president, mayor, admiral, captain—these are terms that convey an image with no effort on your part. Anything the reader doesn’t have to research is good. If you are too enthusiastic in creating an entire language in order to convey a sense of foreignness, you have gone to a great deal of trouble only to lose the majority of readers.

When you are building a world that only exists on paper, you must be sparing with the space you devote to conveying the social, religious, and political climate of your story. This is atmosphere. This is knowledge the characters have, but the reader does not.

There is no need to have an introductory chapter describing the laws and moral codes of the religious order of St Anthony, or the political climate of East Berlin in 1962. The way you convey this is to show how these larger societal influences affect your character and his/her ability to resolve their situation.

You show this in small ways, with casual mentions in conversation ONLY when it becomes pertinent, and not through info dumps.

Familiar words convey familiar images. Use them wisely in showing an entire fantasy world. Consider the politics in a medieval setting:

Setting:

- the village of Imaginary Junction, in the Barony of Blackthorn.

General atmosphere:

- the weather is unseasonably cold

Introduce the protagonist and show him in his situation:

- In an alley, a bard, Sebastian, is hiding.

Introduce the antagonist(s):

- Soldiers of Baron Blackthorn, whom Sebastian has inadvisably humiliated in a song are searching for him.

Introduce the way politics and power affect the protagonist:

- the soldiers surround and capture Sebastian

- he is hauled before the angry baron and

- thrown into prison, sentenced to hang at dawn.

The bolded words above offer a reader powerful images of both the physical and political world Sebastian lives in. These words are familiar to every reader of fantasy. They convey emotions and a feudal atmosphere without you having to resort to an info dump of the history of Imaginary Junction.

Show the coldness of the alley, show the irate nobleman’s anger, show the wretchedness of the protagonist in prison, show the arrogance of the soldiers. Use familiar terms to convey entire packets of images wherever possible, and they will be unobtrusive, allowing the reader to live the story, to fear the coming dawn as much as Sebastian does.

Image Credits and Attributions:

Henry VIII by Hans Holbein 1540 / Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Enrique VIII de Inglaterra, por Hans Holbein el Joven.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Enrique_VIII_de_Inglaterra,_por_Hans_Holbein_el_Joven.jpg&oldid=344005488 (accessed June 2, 2019

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Augustus Edwin Mulready Fatigued Minstrels 1883.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Augustus_Edwin_Mulready_Fatigued_Minstrels_1883.jpg&oldid=335802594 (accessed June 2, 2019).

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Ernst Meyer – A Roman Alley – KMS2097 – Statens Museum for Kunst.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Ernst_Meyer_-_A_Roman_Alley_-_KMS2097_-_Statens_Museum_for_Kunst.jpg&oldid=330745323 (accessed June 2, 2019).

![Pieter Cornelis Dommersen [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/dommersen_gothic_cathedral_in_a_medieval_city.jpg?w=224&h=300)

![Karl Pippich [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/carl_pippich_karlskirche_wien.jpg?w=300&h=200)

![Thomas Cole [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/cole_thomas_the_return_1837.jpg?w=300&h=183)

![I, Sailko [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/benozzo_gozzoli_corteo_dei_magi_1_inizio_1459_51.jpg?w=198&h=300)

![Sir Galahad, George Frederic Watts [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/220px-sir_galahad_watts.jpg?w=147&h=300)

![Shmuser at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/36_inch_reach_extender.jpg?w=146&h=300)