Need shapes the environment and forms an obvious but unobtrusive layer of the world our characters inhabit.

Need shapes the environment and forms an obvious but unobtrusive layer of the world our characters inhabit.

What our characters do for a living, the tools they use, what they must acquire – these things form a layer that grows out of need. This layer shows the reader the level of technology, the society they inhabit, and their standing within that culture. This layer is easy to construct in many ways but can be a stumbling block to the logic of your plot.

First, no matter what genre you are writing in, you must establish the level of technology and stick to it. Do the research and then create your technology.

The Romans had running water, central heating, and toilets in their homes. So did the Minoans. However, all their great architectural creations required human hands to do the physical work. They walked, rode horses, donkeys, or oxen, and were limited to wagons drawn by those same domestic beasts.

In the ordinary environment, cups will be cups, bowls will be bowls. The materials they are made of might be different, but those items will always be the same. Furniture will be similar—people need somewhere to sit or sleep. They need a place to cook and somewhere to store preserved food.

Clothing styles are up to you, but I suggest you keep it simple and don’t wax poetic about it.

Some aspects of a story require planning if you are to keep to the logic of your established world setting.

Characters remain the same, no matter what genre you are writing. Beneath the obvious tropes of a particular genre is a human being. Consider the soldier:

I write fantasy, so the following is an excerpt from a short story written this last year, The Way of the Seventh Door.

Worlds are like clothes. I could drop Jared into any world, and he would still be who he is—a young, hapless schmuck with potential. Genre defines the visuals, but the characters are paper dolls we dress to fit the society we have placed them in. The clothes and world of Soldier Barbie fits Corporate Barbie… and Malibu Barbie… and Star Wars Barbie.

Worlds are like clothes. I could drop Jared into any world, and he would still be who he is—a young, hapless schmuck with potential. Genre defines the visuals, but the characters are paper dolls we dress to fit the society we have placed them in. The clothes and world of Soldier Barbie fits Corporate Barbie… and Malibu Barbie… and Star Wars Barbie.

We will take one protagonist and place them in one of three kinds of settings: fantasy, sci fi, or contemporary. As we go, write your own version of this scene.

- A soldier, your choice of gender, gears up for an impending battle. It will take place on foreign soil and could involve personal, face-to-face combat.

- First, we must consider what garments they might wear.

- Next, we armor them.

- Then we give them weaponry.

- Finally, we equip them with some sort of rations and water, as sustenance becomes an issue if a battle stretches for several days.

- We do it in one paragraph.

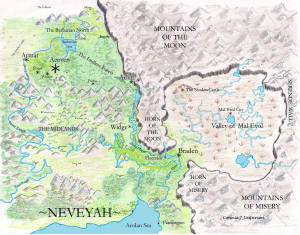

Now let’s put Jared, my luckless protagonist from the previous example into this scenario. Fortunately for the safety of everyone in Neveyah, he isn’t preparing for war, but he does have a mission, and it requires dressing appropriately, and ensuring he has what he might need to complete it:

In any setting, there are certain commonalities with only minor literary differences for soldiers: they all need garments, weapons, armor, and sustenance, and you can use those things to

In any setting, there are certain commonalities with only minor literary differences for soldiers: they all need garments, weapons, armor, and sustenance, and you can use those things to

- offer more clues about your character’s personality and

- set your protagonist up for a meeting with destiny by inserting clues: white armor, new boots – what could go wrong?

Whether the weapon is a rifle, a sword, or a phaser is dependent on the level of technology you have established.

Logic determines how each need is met. In the case of weapons, within each category there are many varieties of each. Which kind of hand-held weapon your protagonist will use is dependent on their skill level and physical strength as well as what is stocked in the armory.

When it comes to weaponry, if you are writing about them, you need to research them to know what is logically possible. Within each of the three world settings, strength and skill are determining factors—a cutlass is an efficient blade and is much lighter than a claymore. A one-handed blade allows the wielder to carry a shield. A shotgun is much lighter than a machine-gun but is less effective, so be true to the logic and research what might be most useful to your characters and don’t introduce an element that doesn’t fit.

Sci-fi writers—I suggest that for advanced weaponry, you should do the research into theoretical applications of lasers, sonic, and other theoretically possible weapons. Sci fi readers know their science, so if you don’t consider the realities of physics, your work won’t appeal to the people who read in that genre.

For soldiers of any technology level, from Roman to medieval, to contemporary, to futuristic—armor will always consist of the same elements: breast and back plate, shin-guards, vambraces, a helmet of some sort, and maybe a shield. These elements won’t vary much, although the materials they’re made of will differ widely from technology to technology. For the sake of expediency and logic, garments must be close-fitting as they will go under the armor.

Expediency affects logic which affects need. The same is true for any occupation–bookkeeper, lawyer, home-maker–the setting changes from genre to genre, but the fundamental needs for each occupation remain the same.

In every aspect of a world, expediency decides what must be mentioned and how important it is. At times, you must go back to an earlier place and make changes that allow for a certain necessary turn of events.

In every aspect of a world, expediency decides what must be mentioned and how important it is. At times, you must go back to an earlier place and make changes that allow for a certain necessary turn of events.

For instance, in a battle situation, food must be extremely compact, lightweight, and must provide nutrients the soldier needs. Nutrition bars, jerky—battle rations and how the soldier carries them must be considered. How do you fit that into the world building? Casually, with one sentence, a few words.

What basic things do you need in your real-world? You need food, water, clothing, and shelter, and a means of providing those things. Place the character in a room and call it a kitchen, and the reader will immediately imagine a kitchen. Mention the coffeemaker, and the reader’s mind will furnish the cups.

Need manifests in other, more subtle ways.

Do you require a way to communicate with others quickly? Messengers, letters, telephones, social media, or telepathy? Choose a method for long distance communication that fits your technology and stick to it.

If you are writing a sci fi tale, what sort of personal power does that technology confer on the characters? What powers it? What are the limits of that technology, and how do those limits hamper the protagonist? What do they need to acquire to overcome those limitations?

If magic is a part of your world, you must design the way it is used, what powers it, and set rigid limits. Limits create opportunities for both failure and creative thinking.

In all levels of technology, some of what the characters need should be denied to them.

Obstruction offers the opportunity for heroism.

No matter the genre, need and human failure makes the story more real.

Next week, we will explore the commonalities of science and magic and how they are applied to world building.

Credits and Attributions:

Excepts from The Way of the Seventh Door, © Connie J. Jasperson 2019, All Rights Reserved.

Gladys Parker [Public domain] “Mopsy Modes” paper doll published in TV Teens, Vol. 2, No. 9 Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Mopsy Modes – TV Teens, Vol. 2, No. 9.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Mopsy_Modes_-_TV_Teens,_Vol._2,_No._9.jpg&oldid=344503399 (accessed May 21, 2019).

Metropolitan Museum of Art [CC0] Japanese Paper Doll, ca. 1897-1898 Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:MET DP147723.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:MET_DP147723.jpg&oldid=305535412 (accessed May 21, 2019).

![Hunter in Winter Wood, by George Henry Durrie 1860 [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/george_henry_durrie_-_hunter_in_winter_wood.jpg?w=300&h=197)

![By vlasta2, bluefootedbooby on flickr.com [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/518px-the-art-of-war-bamboo_book_-_binding_-_ucr.jpg?w=259&h=300)