As most of you know by now, I regularly participate in the annual writing rumble known as NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month). I’m a rebel in that I usually scratch out as many short stories as I am able in those thirty days.

I participate every year because for 30 precious days, writing is the only thing I “have” to do.

My friends and family all know that November, in our house, is referred to “National Pot Pie Month,” so if you drop by expecting a hot meal from Grandma, it will probably emerge from the microwave in the form of a formerly frozen hockey puck.

My friends and family all know that November, in our house, is referred to “National Pot Pie Month,” so if you drop by expecting a hot meal from Grandma, it will probably emerge from the microwave in the form of a formerly frozen hockey puck.

I usually have my “winners’ certificate” by the day they become available, but I continue writing every day through the 30th and update my word count daily.

NaNoWriMo is a contest in the sense that if you write 50,000 words and have your word count validated through the national website you ‘win.’ But it is not a contest in any other way as there are no huge prizes or great amounts of acclaim for those winners, only a PDF winner’s certificate that you can fill out and print to hang on your wall.

It is simply a month that is solely dedicated to the act of writing a novel.

Now let’s face it–a novel of only 50,000 words is not a very long novel. It’s a good length for YA or romance, but for epic fantasy or literary fiction it’s only half a novel. But regardless of the proposed length of their finished novel, a dedicated author can get the rough draft–the basic structure and story-line of a novel–down in those thirty days simply by sitting down for an hour or two each day and writing a minimum of 1667 words per day.

With a simple outline to keep you on track, that isn’t too hard. In this age of word processors, most authors can double or triple that. As always, there is a downside to this intense month of stream-of-consciousness writing. Just because you can sit in front of a computer and spew words does not mean you can write a novel that others want to read.

Every year many cheap or free eBooks will emerge testifying to that fundamental truth.

The good thing is, over the next few months many people will realize they enjoy the act of writing and are fired to learn the craft. They will find that for them this month of madness was not about getting a certain number of words written by a certain date, although that goal was important. For them, it is about embarking on a creative journey and learning a craft with a dual reputation that difficult to live up to. Depending on the cocktail party, authors are either disregarded as lazy ne’er-do-wells or given far more respect than we deserve.

As I said in my previous post on NaNoWriMo, more people do this during November than you would think–about half the NaNo Writers in my regional area devote this time journaling or writing college papers.

For a very few people, participating in NaNoWriMo will give them the confidence to admit that an author lives in their soul and is demanding to get out. In their case, NaNoWriMo is about writing and completing a novel they had wanted to write for years, something that had been in the back of their minds for all their lives.

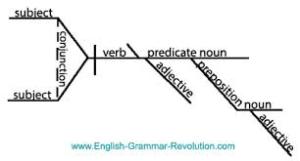

These are the people who will join writing groups and begin the long journey of learning the craft of writing. Whether they pursue formal educations or not, these authors will take the time and make an effort to learn writing conventions (practices). They will attend seminars, they will develop the skills needed to take a story and make it a novel with a proper beginning, a great middle, and an incredible end.

They will properly polish their work and run it past critique groups before they publish it. They will have it professionally edited. These are books I will want to read.

The life of an artist or author is not one of constant accolades and fetes. After you have downloaded the PDF Winners’ Certificate from www.NaNoWriMo.org, you will rarely receive an award to show for your labors. Yes, some people will love and admire what we have created, but other times what we hear back from our beta readers and editors is not what we wanted to hear.

The smart authors haul themselves to a corner, lick their wounds, and persevere. They pull up their socks and keep to the path and don’t expect or demand overnight success.

When we write something that a reader loves—that is a feeling that can’t be described. That moment makes the months of intense work and financial sacrifice worth it.

And whether we go indie or the traditional route, writing is a career that will require financial sacrifice.

Most authors must keep their day jobs because success as an author can’t always be measured in cash or visibility in the New York Times bestsellers list. For most authors, success can only be measured in the satisfaction you as an author get out of your work. Traditionally published authors see a smaller percentage of their royalties than the more successful indies, but if they are among the lucky few, they can sell more books and earn more because of that.

The fact your book has been picked up by a traditional publisher does not guarantee they will put a lot of effort into pushing the first novel by an unknown author. You will have to do all the social media footwork yourself, tweeting, getting an Instagram account, getting a website, etc. You may even have to arrange your own book signing events, just as if you were an indie.

This is time-consuming, and you will feel as if you need a personal assistant to handle these things—indeed, some people rely on the services of hourly personal assistants to help navigate the rough waters of being your own publicist.

Every year, participating in NaNoWriMo will inspire many discussions about becoming an author. Going full-time or keeping the day job, going indie or aiming for a traditional contract—these are conundrums many new authors will be considering after they have finished the chaotic month of NaNoWriMo. While few of us have the luxury to go indie and write full-time (my husband has a good job), many authors will struggle to decide their publishing path.

However, if you don’t sit down and write that story, you aren’t an author. You won’t have to worry about it. With that in mind, November and NaNoWriMo would be a great time to put that idea on paper and see if you really do have a novel lurking in your future.

![IBM Selectric, By Oliver Kurmis [CC BY 2.5] via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ibm_selectric-1.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![Joos van Craesbeeck [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/joos_van_craesbeeck_-_death_is_quick_-_quarrel_in_a_pub.jpg?w=300&h=217)