If you have been writing for any length of time, you have probably discovered that there is an art to both writing and selling short stories.

If you have been writing for any length of time, you have probably discovered that there is an art to both writing and selling short stories.

It is only when we begin reading widely, and in many different genres, that we discover a painful truth: great writing is not merely a matter of following rules.

As an editor and a voracious reader, I often find a special kind of life in a manuscript that has broken some of the rules.

However, poorly constructed work will be rejected by all publishers, and no reason will be given.

Grammar rules exist for a purpose, and haphazard breaking of them can destroy a reader’s enjoyment of a story. I guarantee you won’t find a publisher for that story.

If you want to sell your work, you must know the rules of grammar and have a basic understanding of mechanics. These rules exist for the comfort and convenience of the reader, so don’t think that they don’t matter.

The four fundamental laws of comma use are not open to interpretation, but are simple and easy to learn. Be consistent in their use.

1) Never insert commas “where you take a breath” because everyone breathes differently.

2) Do not insert commas where you think it should pause, because every reader sees the pauses differently.

3) Use commas to join two independent clauses when they are joined by a conjunction. The independent clause is a complete stand-alone sentence.

- Edgar worships the ground I walk on, but his adoration bores me.

4) Don’t use a comma to join a dependent clause to an independent clause.

- Edgar worships the ground I walk on and brings me my coffee.

If you understand those four concepts, you are probably ahead of the competition.

Unfortunately, it is easy to murder what began as a beautiful story. Consider those writers who spend years carefully combing every spark of accidental passion out of their work, creating textbook-perfect sentences that are flat, toneless.

Other authors randomly have characters swear, not consistently, but off and on, apparently for the shock value. Others might inject a little graphic violence or sex into the spots where they couldn’t think of what to do next.

When you do anything that breaks a rule, you must do it consistently and with purpose.

“Shock” for the sake of shock has no value to offer. However, a well-written manuscript may shock and challenge you.

When you understand how a story is constructed, you’re able to find creative ways to phrase things and still keep the story interesting.

When the way you write prose goes against the accepted practice, do it intentionally.

Be sure to tell your editor what rules you are choosing to ignore and why, and she will make sure you are consistent.

We all begin at the same place as writers, all of us mortals with flaws and our own way of doing things.

So now that we understand we all begin as novices, I must ask you this question:

Are you writing because you’re burning to tell a story? If you are not writing for the joy of writing, quit now. You’ll never sell a story you don’t believe in.

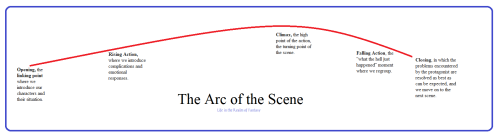

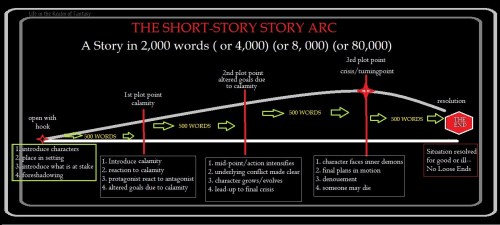

Otherwise, keep writing. Only by continued practice and attention to learning the craft will you develop the balance you know you need. Purchase the Chicago Guide to Grammar Usage and Punctuation, and learn how sentences and paragraphs are constructed. Then learn how to fit those sentences and paragraphs into a story arc.

That way, when you break a rule, you will be knowledgeable and do it with style.

The best way to gain a handle on all aspects of writing fiction is by writing short stories and essays.

With each short-story you write, you increase your ability to tell a story with minimal exposition and intentional prose. This is especially true if you limit yourself to writing the occasional practice story, telling the whole story in 1000 words or less. These practice shorts serve several purposes:

- You have a finite amount of time to tell what happened, so only the most crucial of information will fit within that space.

- You have a limited amount of space, so your characters will be restricted to just the important ones.

- There is no room for anything that does not advance the plot or influence the outcome.

- You will build a backlog of short stories and characters to draw on when you need a good story to submit to a contest.

For me, the most difficult challenge is to write flash fiction, where I have less than 1,000 words to tell a story. This means we only include the most essential elements of a story. All my stories are either shorter or longer than 1,000 words and require weeks of effort to get them to fit that parameter.

For me, the most difficult challenge is to write flash fiction, where I have less than 1,000 words to tell a story. This means we only include the most essential elements of a story. All my stories are either shorter or longer than 1,000 words and require weeks of effort to get them to fit that parameter.

As a poet, I find it far easier to tell a story in 100 words than in 1,000. That 100-word story is called a drabble and is an art form in itself.

Many people have asked how to find places that are accepting submissions. That can be a challenge, but these are links to two groups on Facebook where publishers post open calls for short stories.

Open Submission Calls for Short Story Writers (All genres, including poetry)

Open Call: Science Fiction, Fantasy & Pulp Market (speculative fiction only)

You do have to apply to be accepted into these groups and answer specific questions to prove you are legitimately seeking places to submit your work. Once you are approved, certain rules must be followed for a happy coexistence.

Some open calls are for anthologies that are not paid, others pay royalties. I would carefully check out the unpaid ones to make sure there is a good reason why it is unpaid, and that the publisher is reputable.

Be sure any contracts limit the use to that volume only, and you retain all other rights.

Also, you should retain the right to republish that story after a finite amount of time has passed, usually 90 days after the anthology publication date.

SFWA has a wonderful list of predatory publishers that you should avoid doing business with. They also have useful information on things that might be found in predatory contracts. You don’t need to be a member to access these. https://www.sfwa.org/

You can find publications with open calls at Submittable. Unfortunately, that has lately become not as useful regarding speculative fiction as it was several years ago. Still, many poetry collections, literary anthologies, and contests use Submittable, so that is an option. https://www.submittable.com/

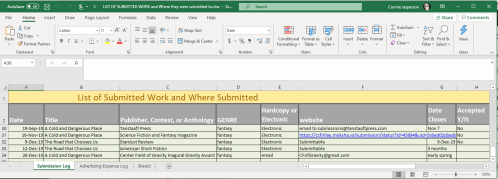

All in all, you have to kiss a lot of frogs, so to speak, before you find that prince of a publisher that is looking for your work. Don’t let one rejection stop you. Keep that submission mill running, and for the love of Isaac Asimov, keep track of who you sent what to, what day you sent it, and whether or not it was accepted.