In the previous post, we discussed how backstory illuminates and makes our characters’ motives logical and reasonable.

But we all know infodumps are an insidious poison, so how do we apply this backstory without losing the reader?

But we all know infodumps are an insidious poison, so how do we apply this backstory without losing the reader?

I spend a lot of time thinking about plot and character, imagining the story, and writing. I have a vision of the story but getting it down isn’t easy. Ideas slip away unless I get them on paper first.

This is the method I use. I create a separate document that is for my use only, and I label it appropriately:

BookTitle_Plot_Core_Conflict.docx

I boil the conflict down to a few paragraphs and refer back to it whenever I find myself rambling.

Most of us know what motivates our protagonist. But our antagonist is frequently a mystery, and the place where the two characters’ desires converge is a mystery. We know the what, but the why eludes us. This can make them less important than the protagonist. Yes, the protagonist is the character we want the reader to sympathize with. But we also want the reader to see the reasoning behind the enemy’s actions, or they won’t be able to suspend their disbelief.

What follows is an example of the short document that is my reminder. These paragraphs summarize the story and detail what motivates the characters. It keeps me focused when I have lost my way:

The root of the matter: The Dark God has assaulted and imprisoned his brother in an effort to steal his wife, and the universe intervened. Now, the gods can only act against each other through the clergy of their world. However, they can corrupt another deity’s clergy through a tainted physical object.

The story: The protagonist and antagonist begin as members of a sect of hunter-mages sworn to serve the Goddess that rules their world. Most of the time, they are mages working as smiths and masons and working as ordinary community members in other crafts. Sometimes they are called to hunt rogue mages and empathically gifted healers who follow the Dark God.

Character A is a shaman, a fire-mage smith and warrior, and is slated to be the next War Leader of the tribes. His shamanic purpose is to unite the people, both the tribes and those citadels who have turned tribeless. He is the chosen champion of the Goddess his sect of mages serves, and his success or failure will determine her fate.

Character A must survive the high shamanic trial to become War Leader. Then he must defeat the Dark God’s champion if he is to have the chance to fulfill his shamanic purpose. Unfortunately, his closest childhood companion is now the champion of the dark side.

Once a devoted follower of the Goddess, Character B triggered a mage trap and was forcibly converted by the Dark God. Character B has always been a traditionalist, a firm believer that the way of the tribes is the only way to keep the people strong. The Dark God twists his loyalty to the tribes and his tribal heritage into a weapon he can use to conquer the Goddess and annex her world. The deities are immortal and can’t be killed, so his quest for total domination threatens the universe’s balance. Each world must have its creator deity, and there can only be one deity for each world.

Before his conversion, Character B was the most dedicated of the sect of rogue mage hunters. After triggering the mage trap, he sees them as the enemy, a cult that stifles and weakens the tribes. He is determined to lead the tribes to conquer the tribeless citadels and regain the power the tribes once wielded.

The Dark God is adept at twisting people’s deeply held beliefs to serve his purpose. He is the ultimate antagonist, acting through the tainted artifact that was able to corrupt Character B. Therefore, Character A’s ultimate goal must be to destroy the mage trap in Character B’s possession. In doing so, he removes Character B’s source of dark power and can fight him on equal ground.

Character A represents teamwork succeeding over great odds. Character B represents the quest for supremacy at all costs.

- Both must see themselves as the hero.

- Both must risk everything to succeed.

- Both must believe they will ultimately win.

When I create the personnel file for my characters, I assign them verbs, nouns, and adjectives, traits they embody. Verbs are action words that reflect how they react on a gut level. Nouns describe their personalities.

They must also have a void – an emotional emptiness, a wound of some sort. Character B knows he has lost something important, something that was central to him. But he refuses to believe he is under a spell of compelling, a pawn in the Gods’ Great Game. He must believe he has agency—this is his void.

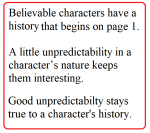

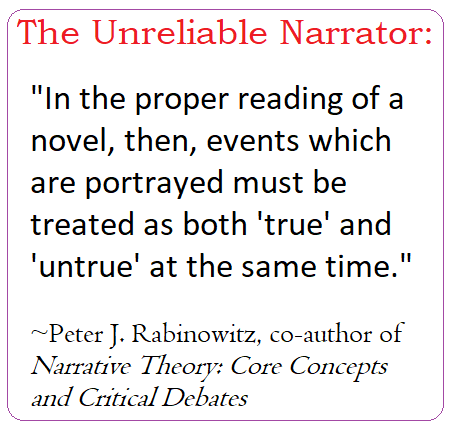

This void is vital because characters must overcome fear to face it. As a reader, one characteristic I’ve noticed in my favorite characters is they each have a hint of self-deception. All the characters – the antagonists and the protagonists – deceive themselves in some way about their own motives.

This void is vital because characters must overcome fear to face it. As a reader, one characteristic I’ve noticed in my favorite characters is they each have a hint of self-deception. All the characters – the antagonists and the protagonists – deceive themselves in some way about their own motives.

My task is to ensure that the stories of Characters A and B intersect seamlessly. Motivations must be clearly defined.

I ask myself what their moral boundaries are. This is where I explore the lengths they will go to achieve their goal. I like to know their limits because even cartoon supervillains draw the line at doing something.

Even if it is only refusing to eat Brussels sprouts.

Like me.

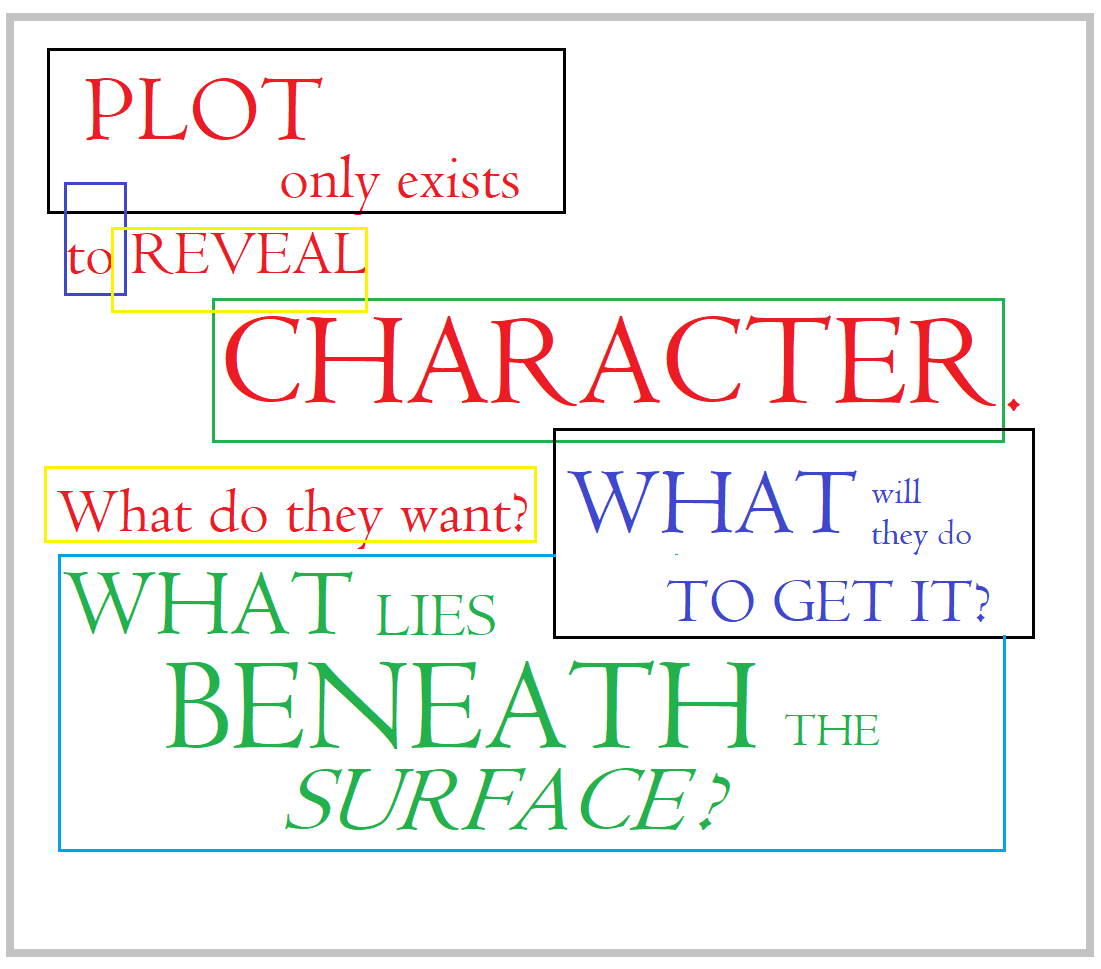

The way my creative mind works, plots evolve out of the characters as I begin picturing them. When I sit down to create a story arc, my characters offer me hints as to how their story will develop.

This evolution can change the course of what I thought the original plot was and sometimes does so radically.

But at some point, the plot must solidify.

The story must finally have an arc that explores the protagonist’s struggle against a fully developed, believable adversary.

My method works for me. It might work for you and takes very little time, only a few paragraphs describing the core of the conflict.

In his book,

In his book,  The story follows a group of

The story follows a group of  However, when the antagonist is a person, I ask myself, why this person opposes the protagonist? What drives them to create the roadblocks they do? Why do they feel justified in doing so?

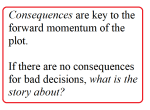

However, when the antagonist is a person, I ask myself, why this person opposes the protagonist? What drives them to create the roadblocks they do? Why do they feel justified in doing so? We must remember that the characters in our stories don’t go through their events and trials alone. We drag the reader along for the ride the moment we begin writing the story. They need to know why they’re in that handbasket and where the enemy thinks they’re going, or the narrative will make no sense.

We must remember that the characters in our stories don’t go through their events and trials alone. We drag the reader along for the ride the moment we begin writing the story. They need to know why they’re in that handbasket and where the enemy thinks they’re going, or the narrative will make no sense. Sometimes, the story demands a death, and 99% of the time, it can’t be the protagonist. But death must mean something, wring emotion from us as we write it. Since the character we have invested most of our time into is the protagonist, we must allow a beloved side character to die.

Sometimes, the story demands a death, and 99% of the time, it can’t be the protagonist. But death must mean something, wring emotion from us as we write it. Since the character we have invested most of our time into is the protagonist, we must allow a beloved side character to die. Mortally wounded, the antagonist, Khan, activates a “rebirth” weapon called Genesis, which will reorganize all matter in the nebula, including Enterprise. Though Kirk’s crew detects the activation and attempts to move out of range, they will not be able to escape the nebula in time without the ship’s inoperable warp drive. Spock goes to restore warp power in the engine room, which is flooded with radiation. When McCoy tries to prevent Spock’s entry, Spock incapacitates him with a

Mortally wounded, the antagonist, Khan, activates a “rebirth” weapon called Genesis, which will reorganize all matter in the nebula, including Enterprise. Though Kirk’s crew detects the activation and attempts to move out of range, they will not be able to escape the nebula in time without the ship’s inoperable warp drive. Spock goes to restore warp power in the engine room, which is flooded with radiation. When McCoy tries to prevent Spock’s entry, Spock incapacitates him with a  You, as the author, must understand what drives and motivates even the walk-on, disposable characters. Are they “a red shirt,” that iconic Star Trek symbol of the throw-away character? Or are they a “Spock,” the beloved friend who offers themselves up to save others?

You, as the author, must understand what drives and motivates even the walk-on, disposable characters. Are they “a red shirt,” that iconic Star Trek symbol of the throw-away character? Or are they a “Spock,” the beloved friend who offers themselves up to save others? Unfortunately, although we asked for a ground-floor condo, we were assigned a second-floor unit. My husband is managing the stairs – slowly. On the good side, we have the god’s-eye view of a wide stretch of beach, the perfect deck overlooking it all.

Unfortunately, although we asked for a ground-floor condo, we were assigned a second-floor unit. My husband is managing the stairs – slowly. On the good side, we have the god’s-eye view of a wide stretch of beach, the perfect deck overlooking it all. Writing is going as well as ever, a little up and down. I’m building the framework for a new story, which I will begin writing on November 1st. The world is already built; it’s an established world with many things that are canon and can’t be changed. So, I’m working my way through the bag of tricks that help me jar things loose.

Writing is going as well as ever, a little up and down. I’m building the framework for a new story, which I will begin writing on November 1st. The world is already built; it’s an established world with many things that are canon and can’t be changed. So, I’m working my way through the bag of tricks that help me jar things loose. Protagonist HER: Anna Lundquist, an unemployed game developer. She inherited an old farm and has moved there. She embarks on creating her own business designing anime-based computer games. Anna is shy, not good with men unless discussing books or computer games. VOID: Loss of family. VERBS: Create, Build, Seek, Defend, Fight, Nurture. Modifiers: Adaptable, ambitious, focused, independent, industrious, mature, nurturing, private, resourceful, responsible, simple, thrifty.

Protagonist HER: Anna Lundquist, an unemployed game developer. She inherited an old farm and has moved there. She embarks on creating her own business designing anime-based computer games. Anna is shy, not good with men unless discussing books or computer games. VOID: Loss of family. VERBS: Create, Build, Seek, Defend, Fight, Nurture. Modifiers: Adaptable, ambitious, focused, independent, industrious, mature, nurturing, private, resourceful, responsible, simple, thrifty. Antagonist HIM: Matt Gentry, owner of MGPopularGames and Anna’s former boss, is angry at Anna for leaving his firm. On a skiing trip with an old fraternity brother who owns an art supply store in Starfall Ridge, he sees her entering Nic’s coffeeshop. Matt discovers that Anna is now living in that town. He learns she has started her own company and is building an anime-based RPG. He goes back to Seattle and files an injunction to stop her, claiming that he owns the rights to her intellectual property. VOID: Narcissist. VERBS: Possess, Control, Desire, Covet, Steal, Lie, Torment.

Antagonist HIM: Matt Gentry, owner of MGPopularGames and Anna’s former boss, is angry at Anna for leaving his firm. On a skiing trip with an old fraternity brother who owns an art supply store in Starfall Ridge, he sees her entering Nic’s coffeeshop. Matt discovers that Anna is now living in that town. He learns she has started her own company and is building an anime-based RPG. He goes back to Seattle and files an injunction to stop her, claiming that he owns the rights to her intellectual property. VOID: Narcissist. VERBS: Possess, Control, Desire, Covet, Steal, Lie, Torment.

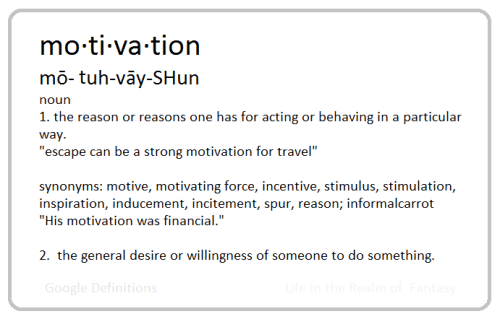

Firing Chekhov’s gun brings us to motivation. I learned “the 5 W’s” of journalism when I was in grade school. Yes, back in the Stone Age they assumed 12-year-old children were considering their adult careers, and journalism was a respected path to aspire to. I don’t know if they still teach them, but they should.

Firing Chekhov’s gun brings us to motivation. I learned “the 5 W’s” of journalism when I was in grade school. Yes, back in the Stone Age they assumed 12-year-old children were considering their adult careers, and journalism was a respected path to aspire to. I don’t know if they still teach them, but they should. What motivates Anna?

What motivates Anna? Unfortunately, David has been suffering from crippling writers’ block and has begun to seek inspiration in alcohol and an affair with the wife of a close friend. He loves Anna, and desperately wants to end that illicit relationship.

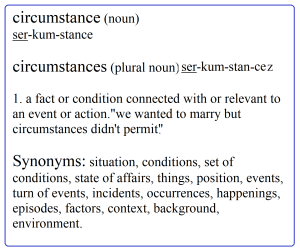

Unfortunately, David has been suffering from crippling writers’ block and has begun to seek inspiration in alcohol and an affair with the wife of a close friend. He loves Anna, and desperately wants to end that illicit relationship. Once I get a bit deeper into writing a story, circumstances will have changed at the midpoint. Do these changes affect the characters’ wants and needs? If so, I make a note of that on my stylesheet.

Once I get a bit deeper into writing a story, circumstances will have changed at the midpoint. Do these changes affect the characters’ wants and needs? If so, I make a note of that on my stylesheet. To achieve a sense of depth, we begin with simplicity. Each character’s sub-story must be built upon who these characters think they are.

To achieve a sense of depth, we begin with simplicity. Each character’s sub-story must be built upon who these characters think they are. They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth.

They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth.