Our stories are an unconscious reflection of what we wish our favorite authors would write. But what is it that attracts us to their writing?

We love their style, their voice.

Some authors are forceful in their style and throw you into the action. They have an in-your-face, hard-hitting approach that comes on strong and doesn’t let up until the end.

Some authors are forceful in their style and throw you into the action. They have an in-your-face, hard-hitting approach that comes on strong and doesn’t let up until the end.

Others are more leisurely, casually inserting small hooks that keep you reading.

What are voice and style?

- The habitual choice of words shapes the tone of our writing.

- The chronic use and misuse of grammar and punctuation shapes the pacing of our sentences.

- Our deeply held beliefs and attitudes emerge and shape character arcs and plot arcs.

We develop our own voice and style when we write every day or at least as often as possible. We subconsciously incorporate our speech patterns, values, and fears into our work, and those elements of our personality form the voice that is ours and no one else’s.

The words we habitually choose are a part of our fingerprint. First drafts are rife with crutch words. This is because, in the rush of laying down the story, we tend to fall back on certain words and ignore their synonyms. A good online thesaurus is a necessary resource.

I prefer to keep my research in hardcopy form, rather than digital. I have mentioned this before, but The Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms is a handy tool when I am stuck for alternate ways to say something.

I prefer to keep my research in hardcopy form, rather than digital. I have mentioned this before, but The Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms is a handy tool when I am stuck for alternate ways to say something.

And it makes the perfect place to rest my teacup.

We all have words that we choose above others because they say precisely what we mean. I think of my fallback words as a code. At this point in my career, I know what those words are and when I am making revisions, I make a global search for them and insert alternatives that show my idea more vividly.

Looking at each example of a code word and their synonyms gives me a different understanding of what I am trying to say. It gives me the opportunity to change them to a more powerful form, which conveys a stronger image and improves the narrative. (I hope.)

Saying more with fewer words forces us to think on an abstract level. In poetry we have to choose our words based on the emotions they evoke, and the way they portray the environment around us. This is why I gravitate to narratives written by authors who are also poets—the creative use of words elevates what could be mundane to a higher level of expression, and when it’s done well, the reader doesn’t consciously notice the prose, but they are moved by it.

What are some words that convey powerful imagery, some that heighten tension when included in the prose?

- Lunatic

- Lurking

- Massacre

- Meltdown

- Menacing

- Mired

- Mistake

- Murder

- Nightmare

- Painful

- Pale

- Panic

- Peril

- Slaughter

- Slave

- Strangle

- Stupid

- Suicide

- Tailspin

- Tank

- Targeted

- Teetering

And those are just the beginning.

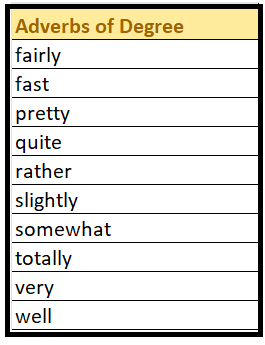

Our word choices are a good indication of how advanced we are in the craft of writing. For instance, in online writing forums, we are told to limit the number of modifiers (adjectives and adverbs) we might habitually use.

We are like everyone else. Our work is as dear to us as a child, and we can be just as touchy as a proud parent when it is criticized. We should respect the opinions of others, but we have the choice to ignore those suggestions if they don’t work for us.

Our voice comes across when we write from the heart. We gain knowledge and skill when we study self-help books, but we must write what we are passionate about. So, the rule should be to use modifiers, descriptors, or quantifiers when they’re needed.

How we use them is part of our style. Modifiers change, clarify, qualify, or sometimes limit a particular word in a sentence to add emphasis, explanation, or detail. We also use them as conjunctions to connect thoughts: “otherwise,” “then,” and “besides.”

Descriptors are adverbs and adjectives that often end in “ly.” They are helper nouns or verbs, words that help describe other words. Some descriptors are necessary but they are easy to overuse.

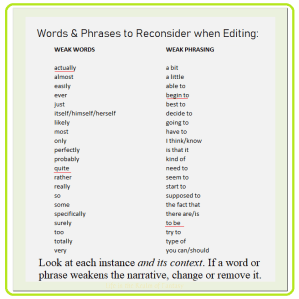

Do a global search for the letters “ly.” A list will pop up in the left margin and the manuscript will become a mass of yellow highlighted words.

I admit it takes time and patience to look at each instance to see how they fit into that context. If, after looking at the thesaurus, I discover that the problem descriptor is the only word that works, I will have to make a choice: rewrite the passage, delete it, or leave it.

Quantifiers are abstract nouns or noun phrases that can weaken prose. They convey a vague impression or a nebulous quantity, such as: very, a great deal of, a good deal of, a lot, many, much, and rather. Quantifiers have a bad reputation because they can quickly become habitual, such as the word very.

We don’t want our narrative to feel vague, nebulous, or abstract.

- In some instances, we might want to move the reader’s view of a scene or situation out, a “zoom out” so to speak. The brief use of passive phrasing will do that. I saw the gazelles leaping and running ahead of the grassfire, hoping to outrun it. They failed.

I saw is a telling phrase, slightly removing the speaker from the trauma.

Limiting descriptors and quantifiers to conversations makes a stronger narrative. We use these phrases and words in real life, so our characters’ conversations will sound natural. The fact we use them in our conversation is why they fall into our first drafts.

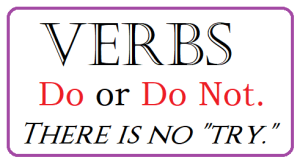

Our narrative voice comes across in our choice of hard or soft words and where we habitually position verbs in a sentence. It is a recognizable fingerprint.

Our narrative voice comes across in our choice of hard or soft words and where we habitually position verbs in a sentence. It is a recognizable fingerprint.

Many times, I read something, and despite how well it is constructed and written, it doesn’t ring my bells. This is because I’m not attracted to the author’s style or voice.

That doesn’t mean the work is awful. It only means I wasn’t the reader it was written for.

It follows that certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. Code words are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One word, one packet of letters will serve many purposes and convey a myriad of mental images.

It follows that certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. Code words are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One word, one packet of letters will serve many purposes and convey a myriad of mental images. I want to avoid that sin in my work, but what are my code words? What words are being inadvertently overused as descriptors? A good way to discover this is to make a word cloud. The words that see the most screen time will be the largest.

I want to avoid that sin in my work, but what are my code words? What words are being inadvertently overused as descriptors? A good way to discover this is to make a word cloud. The words that see the most screen time will be the largest.  endured

endured Sometimes, the only thing that works is the brief image of a smile. Nothing is more boring than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I want to know what is happening inside our characters and can be put off by an exaggerated outward display.

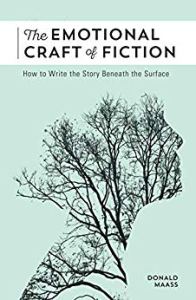

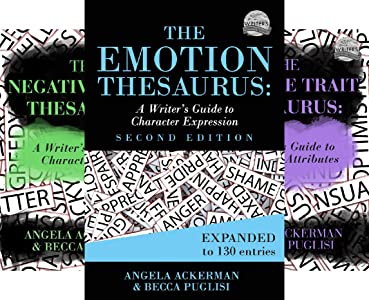

Sometimes, the only thing that works is the brief image of a smile. Nothing is more boring than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I want to know what is happening inside our characters and can be put off by an exaggerated outward display. If you don’t have it already, a book you might want to invest in is

If you don’t have it already, a book you might want to invest in is  One thing I notice when listening to an audiobook is crutch words. One of my favorite authors uses the descriptor “wry” in all its forms, just a shade too frequently. As a result, I have scrubbed it from my own manuscript, except for one instance.

One thing I notice when listening to an audiobook is crutch words. One of my favorite authors uses the descriptor “wry” in all its forms, just a shade too frequently. As a result, I have scrubbed it from my own manuscript, except for one instance. The words authors choose add depth and shape their prose in a recognizable way—their voice. They “paint” a scene showing what the point-of-view character sees or experiences.

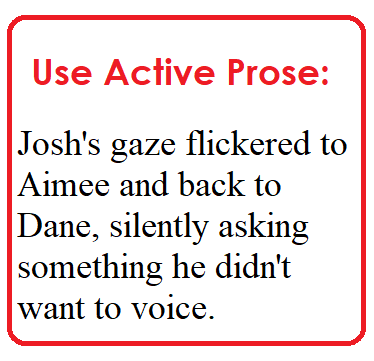

The words authors choose add depth and shape their prose in a recognizable way—their voice. They “paint” a scene showing what the point-of-view character sees or experiences. What are descriptors? Adverbs and adjectives, known as descriptors, are helper nouns or verbs—words that help describe other words.

What are descriptors? Adverbs and adjectives, known as descriptors, are helper nouns or verbs—words that help describe other words. However, if you have used “actually” to describe an object, take a second look to see if it is necessary.

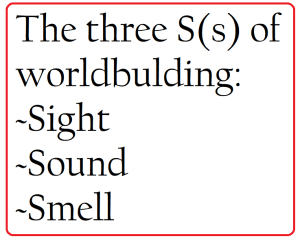

However, if you have used “actually” to describe an object, take a second look to see if it is necessary. The scene I detailed above could be shown in many ways. I took a paragraph’s worth of world-building and pared it down to 19 words, three of which are action words.

The scene I detailed above could be shown in many ways. I took a paragraph’s worth of world-building and pared it down to 19 words, three of which are action words.