I love this painting and all the crazy imagery that witty, sarcastic, and distinctly un-noble Pieter Brueghel the elder. stuffed into it. I first discussed this painting on May 4, 2018, but it has been on my mind since last week when we looked at a seascape by the same artist.

I love this painting and all the crazy imagery that witty, sarcastic, and distinctly un-noble Pieter Brueghel the elder. stuffed into it. I first discussed this painting on May 4, 2018, but it has been on my mind since last week when we looked at a seascape by the same artist.

I love a good allegorical painting, especially when the artist has a point to make. Brueghel the Elder, had a wicked sense of humor, and he wasn’t shy about pointing out the many hypocrisies and foibles of the society around him.

I consider this one of the best, most hilarious allegorical paintings of all time. The Netherlandish Proverbs (also known as The Dutch Proverbs) by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, was painted in 1559. I’ll just say that Pieter Brueghel the Elder is one of my favorite artists.

Quote from Wikipedia:

Critics have praised the composition for its ordered portrayal and integrated scene. There are approximately 112 identifiable proverbs and idioms in the scene, although Bruegel may have included others which cannot be determined because of the language change. Some of those incorporated in the painting are still in popular use, for instance “Swimming against the tide”, “Banging one’s head against a brick wall” and “Armed to the teeth”. Many more have faded from use, which makes analysis of the painting harder. “Having one’s roof tiled with tarts”, for example, which meant to have an abundance of everything and was an image Bruegel would later feature in his painting of the idyllic Land of Cockaigne (1567).

The Blue Cloak, the piece’s original title, features in the centre of the piece and is being placed on a man by his wife, indicating that she is cuckolding him. Other proverbs indicate human foolishness. A man fills in a pond after his calf has died. Just above the central figure of the blue-cloaked man another man carries daylight in a basket. Some of the figures seem to represent more than one figure of speech (whether this was Bruegel’s intention or not is unknown), such as the man shearing a sheep in the centre bottom left of the picture. He is sitting next to a man shearing a pig, so represents the expression “One shears sheep and one shears pigs”, meaning that one has the advantage over the other, but may also represent the advice “Shear them but don’t skin them”, meaning make the most of available assets.

You can find all of the wonderful proverbs on the painting’s page on Wikipedia, along with the thumbnail that depicts the proverb.

My favorite proverbs in this wonderful allegory?

Horse droppings are not figs. It meant we should not be fooled by appearances.

He who eats fire, craps sparks. It meant we shouldn’t be surprised at the outcome if we attempt a dangerous venture.

Now THAT is wisdom!

ABOUT THE ARTIST, via Wikipedia:

Pieter Bruegel (also Brueghel or Breughel) the Elder, 1525–1530 to 9 September 1569) was among the most significant artists of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, a painter and printmaker, known for his landscapes and peasant scenes (so-called genre painting); he was a pioneer in presenting both types of subject as large paintings.

Van Mander records that before he died he told his wife to burn some drawings, perhaps designs for prints, carrying inscriptions “which were too sharp or sarcastic … either out of remorse or for fear that she might come to harm or in some way be held responsible for them”, which has led to much speculation that they were politically or doctrinally provocative, in a climate of sharp tension in these areas. [2]

Credits and Attributions:

The Netherlandish Proverbs (Also known as The Dutch Proverbs) by Pieter Brueghel the Elder 1559 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Netherlandish Proverbs,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Netherlandish_Proverbs&oldid=829168138 (accessed July 16, 2025).

[2] Wikipedia contributors, “Pieter Bruegel the Elder,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder&oldid=1299614602 (accessed July 16, 2025).

![Nicolaes Maes, The Account Keeper, ca. 1656, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/nicolaes_maes_-_the_account_keeper.jpg?w=500)

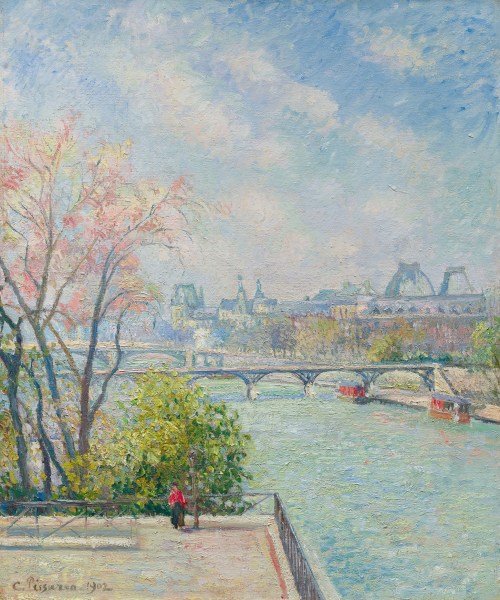

Artist: Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

Artist: Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)