We have two weeks to go to November 1st. If you are planning to participate in a writing quest with a specific goal, now is a good time to consider the world in which your prospective story might be set.

I like to sit somewhere quiet and let my mind wander, picturing the place where the opening scene takes place.

I like to sit somewhere quiet and let my mind wander, picturing the place where the opening scene takes place.

Is it indoors? Are we out in the wild? How can I write this? A few notes about my thoughts will help.

A good way to develop the skill of writing an environment is to visualize the world in your real life. When you look out the window, what do you see? Close your eyes and picture the place where you are at this moment. With your eyes still closed, tell me what it’s like.

If you can describe the world around you with your eyes closed, you can create a world for your characters.

The plants and landscape of my fictional world are partly based on the scenery of Western Washington State because it’s wild and beautiful, and I’m familiar with it. The wild creatures are somewhat reality-based but are mostly imaginary.

Remember, we don’t have to immerse ourselves immediately. All we’re doing is laying the groundwork, ensuring plenty of ideas are handy when we start writing in earnest on November 1st.

Religion is a large part of my intended story, and some things are canon, as the first book in the series was published in 2012. The tagline for this series is “The Gods are at War, and Neveyah is the Battlefield.” The war of the gods broke three worlds, drastically changing the landscape of Neveyah and offering endless opportunities for mayhem.

The novel I intend to finish this year is set at the end of the first millennium, while last year’s effort was set in the second century after the cataclysm canonically known as the Sundering of the Worlds. This means the world is very different. The forests and wildlife have had a thousand years to rebound, and while some areas are still struggling to recover, most of the west is lush in comparison.

The novel I intend to finish this year is set at the end of the first millennium, while last year’s effort was set in the second century after the cataclysm canonically known as the Sundering of the Worlds. This means the world is very different. The forests and wildlife have had a thousand years to rebound, and while some areas are still struggling to recover, most of the west is lush in comparison.

I live only sixty-five miles north of Mount St. Helens, so I have a good local example of how things look after a devastating event. I also can see how flora and fauna rebound in the years following it. Mount St. Helens – Wikipedia

I live only sixty-five miles north of Mount St. Helens, so I have a good local example of how things look after a devastating event. I also can see how flora and fauna rebound in the years following it. Mount St. Helens – Wikipedia

Even if ecological disasters, technology, or religion aren’t the center of the plot, they can be a part of the background, lending color to the world. In Neveyah, my fictional world, the Temple of Aeos trains mages and healers who are then posted to local communities where they serve the people with their gifts.

Those communities are autonomous as the Temple doesn’t run them, but just as in real life, somebody is in charge of running things. In Neveyah, a council of elders governs most towns and cities, and the Temple is run the same way. We humans are tribal. We prefer an overarching power structure leading us because someone has to be the leader.

We call that power structure a government.

When you create a fictional world, you create a culture. As a society, the habits we develop, the gods we worship, the things we create and find beautiful, and the foods we eat are products of our culture.

When you create a fictional world, you create a culture. As a society, the habits we develop, the gods we worship, the things we create and find beautiful, and the foods we eat are products of our culture.

What does the outdoor world look and smell like? Mentioning sights, sounds, and scents can show the imaginary world in only a few words.

What about the weather? It can be shown in small, subtle ways, making our characters’ interactions and the events they go through feel real.

Once you have decided on your overall climate, consider your level of technology. Do some research now and bookmark the websites with the best information.

- A note about fantasy and sci-fi food: climate and soil types limit the variety of food crops that can be grown. Wet and rainy areas will grow vastly different crops from those in arid climates, as will sandy soils and clays versus fertile loams. Look up what sort of food your people will have available to them if your story is set in an exotic environment.

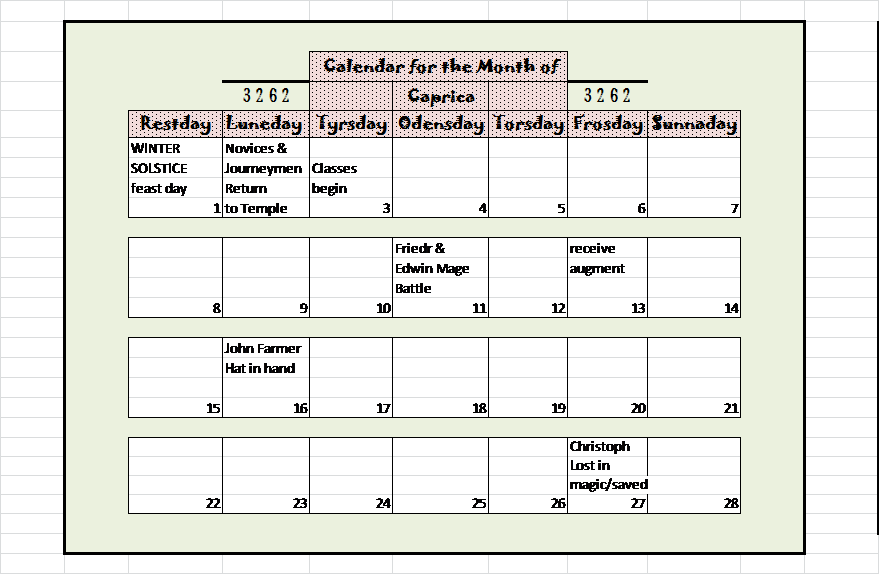

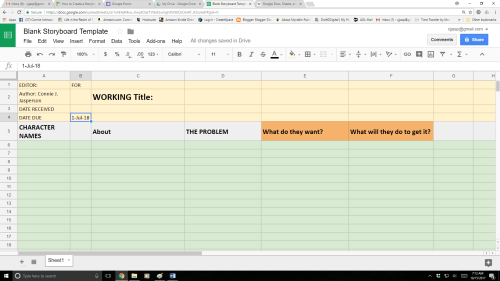

I will be pantsing it (writing stream-of-consciousness) for the month of November, which means I will be writing new words every day, connecting the events I have plotted on my storyboard. I never have time to think about logic once I begin the challenge, so the storyboard is crucial to me.

To show a world plausibly and without contradictions, we must consider how things work, whether it takes place in a medieval world or on a space station. Don’t introduce skills and tech that can’t exist or don’t fit the era.

To show a world plausibly and without contradictions, we must consider how things work, whether it takes place in a medieval world or on a space station. Don’t introduce skills and tech that can’t exist or don’t fit the era.

For instance, blacksmiths create and repair things made of metal. The equivalent of a medieval blacksmith on a space station will have high-tech tools and a different job title. Readers notice that sort of thing.

For instance, blacksmiths create and repair things made of metal. The equivalent of a medieval blacksmith on a space station will have high-tech tools and a different job title. Readers notice that sort of thing.

Society is always composed of many layers and classes. Rich merchant or poor laborer, priest or scientist—each occupation has a place in the hierarchy and has a chain of command. Take a moment to consider where your protagonist and their cohorts might fit in their society.

Maybe your novel’s setting is a low-tech civilization. If so, the weather will affect your characters differently than one set in a modern society. Also, the level of technology limits what tools and amenities are available to them.

What about transport? How do people and goods go from one place to another?

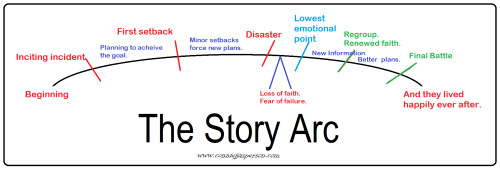

Many things about the world will emerge from your creative mind as you write those first pages and will continue to arise throughout the story’s arc.

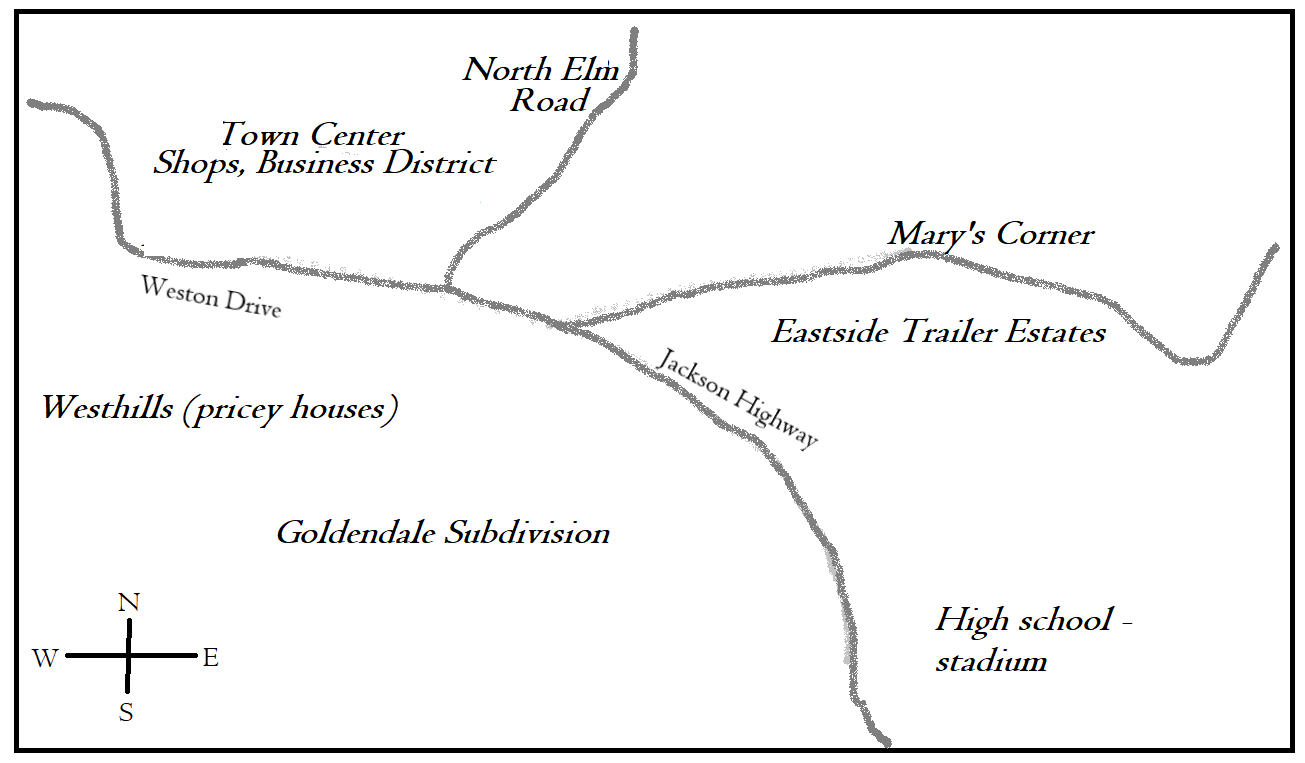

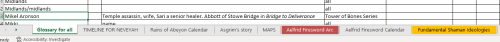

Consider making a glossary as you go. If you are creating names for people or places, list them separately as they come to you. That way, their spelling won’t drift as the story progresses. It happened to me—the town of Mabry became Maury. I put it on the map as Maury, and it was only in the final proofing that I realized that the spelling of the town in chapter 11 was different from that of chapter 30.

A hand-scribbled map and a calendar of events are absolutely indispensable if your characters do any traveling. The map will help you visualize the terrain, and the calendar will keep events in a plausible order.

A hand-scribbled map and a calendar of events are absolutely indispensable if your characters do any traveling. The map will help you visualize the terrain, and the calendar will keep events in a plausible order.

Next week, we’ll take another look at plotting so that we have a starting point with a good hook and a bang-up ending to finish things off.

Credits and Attributions:

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:MSH82 st helens plume from harrys ridge 05-19-82.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:MSH82_st_helens_plume_from_harrys_ridge_05-19-82.jpg&oldid=912891712 (accessed October 13, 2024).

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:St Helens before 1980 eruption horizon fixed.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:St_Helens_before_1980_eruption_horizon_fixed.jpg&oldid=575896084 (accessed October 13, 2024).

Getting those ideas out of your head now is what is important. The bloopers and grammar hiccups can all be ironed out in the second draft.

Getting those ideas out of your head now is what is important. The bloopers and grammar hiccups can all be ironed out in the second draft. Yes, we do need to show moods, and some physical description is necessary. Lips stretch into smiles, and eyebrows draw together. Still, they are not autonomous and don’t operate independently of the character’s emotional state. The musculature of the face is only part of the signals that reveal the character’s interior emotions.

Yes, we do need to show moods, and some physical description is necessary. Lips stretch into smiles, and eyebrows draw together. Still, they are not autonomous and don’t operate independently of the character’s emotional state. The musculature of the face is only part of the signals that reveal the character’s interior emotions. Bad advice is good advice taken to an extreme. But all writing advice has roots in truth. So, when it comes to making revisions, consider these suggestions:

Bad advice is good advice taken to an extreme. But all writing advice has roots in truth. So, when it comes to making revisions, consider these suggestions: I recommend investing in a grammar book, depending on whether you use American or UK English. These books will answer your questions, and you won’t be in doubt about how to use the standard punctuation readers expect to see.

I recommend investing in a grammar book, depending on whether you use American or UK English. These books will answer your questions, and you won’t be in doubt about how to use the standard punctuation readers expect to see. I recommend checking out the NaNoWriMo Store, which offers several books to help you get started. The books available there have good advice for beginners, whether you participate in November’s writing rumble or want to write at your own pace.

I recommend checking out the NaNoWriMo Store, which offers several books to help you get started. The books available there have good advice for beginners, whether you participate in November’s writing rumble or want to write at your own pace. I study the craft of writing because I love it, and I apply the proverbs and rules of advice gently. Whether my work is good or bad—I don’t know. But I write the stories I want to read, so I am writing for a niche audience of one: me.

I study the craft of writing because I love it, and I apply the proverbs and rules of advice gently. Whether my work is good or bad—I don’t know. But I write the stories I want to read, so I am writing for a niche audience of one: me. I am the queen of front-loading too much history in my first drafts. Fortunately, my writer’s group has an unerring eye for where the story really begins.

I am the queen of front-loading too much history in my first drafts. Fortunately, my writer’s group has an unerring eye for where the story really begins. You have done some prep work for character creation, so Tam is your friend. You know his backstory, who he is attracted to (men, women, none, or both), how handsome he is, and his personal history. But none of this matters to the reader in the opening pages. The reader only wants to know what will happen next.

You have done some prep work for character creation, so Tam is your friend. You know his backstory, who he is attracted to (men, women, none, or both), how handsome he is, and his personal history. But none of this matters to the reader in the opening pages. The reader only wants to know what will happen next. Tam and Dagger will tell you what events and roadblocks must happen to them between their arrests and the final victory. This knowledge will emerge from your imagination as you write your way through this first draft.

Tam and Dagger will tell you what events and roadblocks must happen to them between their arrests and the final victory. This knowledge will emerge from your imagination as you write your way through this first draft. Tam will find this information out as the story progresses and we will learn it as he does. With that knowledge, he will realize his fate is sealed—he’s doomed no matter what. But it fires him with the determination that if he goes down, he will take the Warlock Prince and his corrupt Cardinal, with him.

Tam will find this information out as the story progresses and we will learn it as he does. With that knowledge, he will realize his fate is sealed—he’s doomed no matter what. But it fires him with the determination that if he goes down, he will take the Warlock Prince and his corrupt Cardinal, with him.

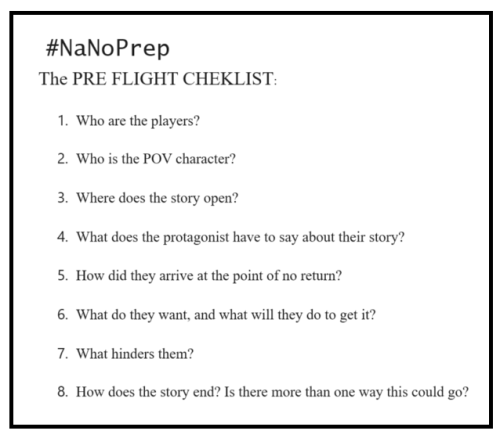

Now, we’re going to hear what our characters have to say about what their story might be.

Now, we’re going to hear what our characters have to say about what their story might be. An important point to remember is that no matter how decent they are, people lie to themselves about their motives. It’s human nature to obscure truths we don’t want to face behind other, more palatable truths. Those secrets will emerge as you write.

An important point to remember is that no matter how decent they are, people lie to themselves about their motives. It’s human nature to obscure truths we don’t want to face behind other, more palatable truths. Those secrets will emerge as you write. In my most recent book,

In my most recent book,  I’m going off-topic here for a moment. While the death of a character stirs the emotions, it must be a crucial turning point in that story. It must be planned and be the impetus that changes everything. The death of a character must drive the remaining characters to achieve greatness.

I’m going off-topic here for a moment. While the death of a character stirs the emotions, it must be a crucial turning point in that story. It must be planned and be the impetus that changes everything. The death of a character must drive the remaining characters to achieve greatness. Unless, of course, you are writing paranormal fantasy. Death and resurrection may be the whole point if that’s the case.

Unless, of course, you are writing paranormal fantasy. Death and resurrection may be the whole point if that’s the case. If your employment isn’t a work-from-home job, using the note-taking app on your cellphone to take notes during business hours will be frowned upon. I suggest keeping a pocket-sized notebook and pencil or pen to write those ideas down as they come to you.

If your employment isn’t a work-from-home job, using the note-taking app on your cellphone to take notes during business hours will be frowned upon. I suggest keeping a pocket-sized notebook and pencil or pen to write those ideas down as they come to you. We talked about getting a start on our characters in Monday’s post. Today, we’re going to visualize the place where our proposed novel is set, the place where the story opens.

We talked about getting a start on our characters in Monday’s post. Today, we’re going to visualize the place where our proposed novel is set, the place where the story opens. All worldbuilding must show a world that feels as natural to the reader as their native environment. I used the forests and lowlands of Western Washington State as my template. The entire series evolved out of three paragraphs that answered the following question:

All worldbuilding must show a world that feels as natural to the reader as their native environment. I used the forests and lowlands of Western Washington State as my template. The entire series evolved out of three paragraphs that answered the following question:

Seagulls are a good example of what could happen. They fly and do their business while on the wing, and sometime find enjoyment in “bombing” windshields.

Seagulls are a good example of what could happen. They fly and do their business while on the wing, and sometime find enjoyment in “bombing” windshields. Some of us (Me! Me!) will make pencil-sketched maps of our fantasy world or the sci-fi setting. I find that maps are excellent brainstorming tools for when I can’t quite jostle a plot loose. It’s a form of doodling, a kind of mind wandering, and helps me find creative solutions to minor obstacles.

Some of us (Me! Me!) will make pencil-sketched maps of our fantasy world or the sci-fi setting. I find that maps are excellent brainstorming tools for when I can’t quite jostle a plot loose. It’s a form of doodling, a kind of mind wandering, and helps me find creative solutions to minor obstacles.

No matter how many characters you think are involved, one will stand out. That person will be the protagonist.

No matter how many characters you think are involved, one will stand out. That person will be the protagonist. Once I know the basic plot, I make a page in my workbook with a bio of each character, a short personnel file. Sometimes, I include images of RPG characters or actors who most physically resemble them and who could play them well—but this is only to cement them in my mind.

Once I know the basic plot, I make a page in my workbook with a bio of each character, a short personnel file. Sometimes, I include images of RPG characters or actors who most physically resemble them and who could play them well—but this is only to cement them in my mind. Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as more intense than one whose name starts with a soft sound. It’s a little thing, but it is something to consider when conveying personalities.

Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as more intense than one whose name starts with a soft sound. It’s a little thing, but it is something to consider when conveying personalities. Every year I participate in

Every year I participate in  Who are the players?

Who are the players? Characters usually arrive in my imagination as new acquaintances inhabiting a specific environment. That world determines the genre.

Characters usually arrive in my imagination as new acquaintances inhabiting a specific environment. That world determines the genre. By just doing that, I will have 50,000 (or more) words by midnight on November 30th.

By just doing that, I will have 50,000 (or more) words by midnight on November 30th. Be willing to be flexible. Do you work best in short bursts? Or, maybe you’re at your best when you have a long session of privacy and quiet time. Something in the middle, a melding of the two, works best for me.

Be willing to be flexible. Do you work best in short bursts? Or, maybe you’re at your best when you have a long session of privacy and quiet time. Something in the middle, a melding of the two, works best for me. A good way to ensure you have that time is to encourage your family members to indulge in their own interests and artistic endeavors. That way, everyone can be creative in their own way during that hour, and they will understand why you value your writing time so much.

A good way to ensure you have that time is to encourage your family members to indulge in their own interests and artistic endeavors. That way, everyone can be creative in their own way during that hour, and they will understand why you value your writing time so much. Writers and other artists do have to make some sacrifices for their craft. It’s just how things are. But don’t sacrifice your family for it.

Writers and other artists do have to make some sacrifices for their craft. It’s just how things are. But don’t sacrifice your family for it. These exercises will only take a few minutes unless you want to spend more time on them. They’re just a warmup, getting you thinking about your writing project. Each post will tackle a different aspect of preparation and won’t take more than ten or fifteen minutes to complete. By the end of this series, my goal is for you to have a framework that will get your project started.

These exercises will only take a few minutes unless you want to spend more time on them. They’re just a warmup, getting you thinking about your writing project. Each post will tackle a different aspect of preparation and won’t take more than ten or fifteen minutes to complete. By the end of this series, my goal is for you to have a framework that will get your project started. I recommend you create a file that contains all the ideas you have in regard to your fictional world, including the personnel files you are creating. I list all my information in an Excel workbook for each book or series, but you can use any kind of document, even handwritten. You just need to write your ideas down. See my post,

I recommend you create a file that contains all the ideas you have in regard to your fictional world, including the personnel files you are creating. I list all my information in an Excel workbook for each book or series, but you can use any kind of document, even handwritten. You just need to write your ideas down. See my post,  So, who is the protagonist of my intended story? Truthfully, in some aspect or another, they will be the person I wish I were. That is how it always is for me—living a fantasy in the safe environment of the novel. Bilbo was J.R.R. Tolkien’s younger self, an inexperienced man discovering the broader world through his wartime experiences. Luke Skywalker was the hero George Lucas always wanted to be.

So, who is the protagonist of my intended story? Truthfully, in some aspect or another, they will be the person I wish I were. That is how it always is for me—living a fantasy in the safe environment of the novel. Bilbo was J.R.R. Tolkien’s younger self, an inexperienced man discovering the broader world through his wartime experiences. Luke Skywalker was the hero George Lucas always wanted to be. If we know their void, we should write it down now, along with any quirky traits they may have. Next, we decide on verbs that will be the driving force of their personality at the story’s opening. Add some adjectives to describe how they interact with the world and assign nouns to show their characteristics.

If we know their void, we should write it down now, along with any quirky traits they may have. Next, we decide on verbs that will be the driving force of their personality at the story’s opening. Add some adjectives to describe how they interact with the world and assign nouns to show their characteristics. Making lists of names is essential. You want their spellings to remain consistent and being able to return to what you initially planned is a big help later on. When we commence writing the actual narrative, each character will have an arc of growth, and sometimes names will change as the story progresses. Do remember to make notes of those changes.

Making lists of names is essential. You want their spellings to remain consistent and being able to return to what you initially planned is a big help later on. When we commence writing the actual narrative, each character will have an arc of growth, and sometimes names will change as the story progresses. Do remember to make notes of those changes.