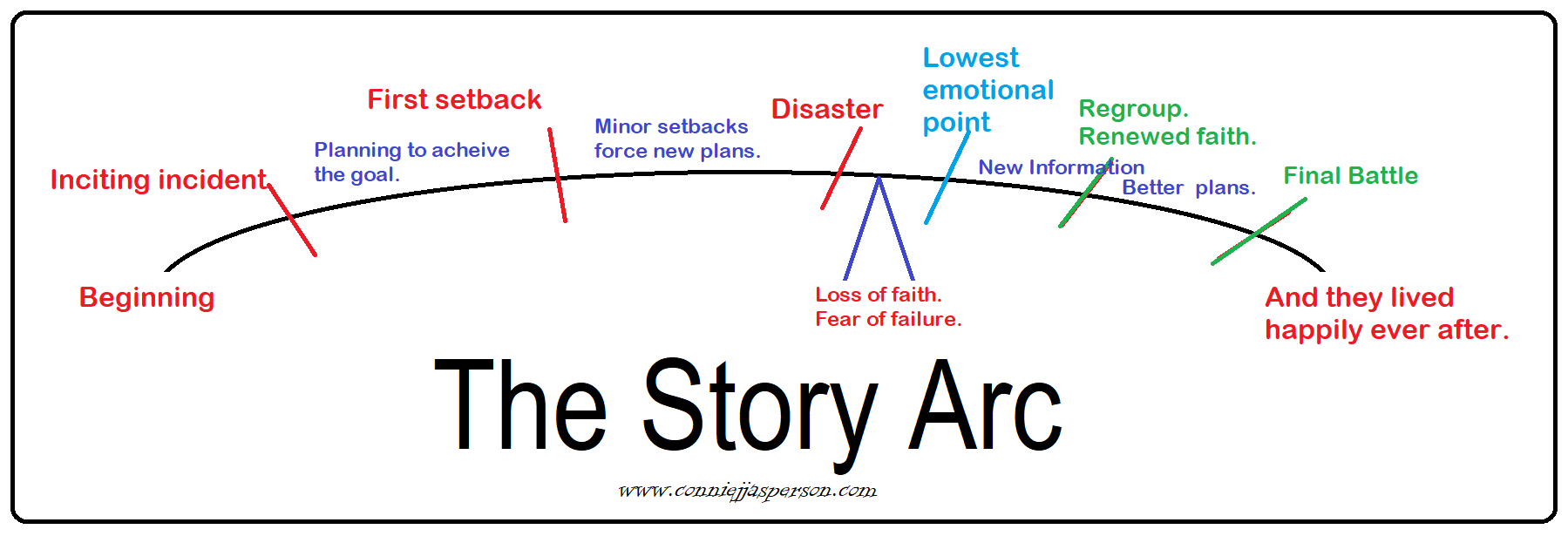

Today, we’re continuing to prep our novel by thinking about the arc of a plot and the story our characters will live out on the page.

We’ll start by jumping to the end.

(I know it’s rude to read the end of a book before you even begin it, but I am the kind of writer who needs to know how it ends before I can write the beginning.)

(I know it’s rude to read the end of a book before you even begin it, but I am the kind of writer who needs to know how it ends before I can write the beginning.)

Julian Lackland was my first completed novel. The first draft of this novel was my 2010 NaNoWriMo project. The entire novel was inspired by a short story of about 2500 words that I had written about an elderly knight-at-large. Julian was a Don Quixote type of character and he had returned to the town where he had spent his happiest days in a mercenary crew.

Golden Beau, Julian’s life-partner has died. Julian enters the town and finds it completely changed. The town has grown so large that he becomes lost. Julian talks to his horse, telling him how wonderful the place they are going to is and all about the people he once knew and loved. When he does find the inn that he’s looking for, nothing is what he expects.

On October 28, 2010, I was scrambling, trying to find something I could write, but my thoughts kept returning to the old man’s story. The innkeeper had referred to him as the Great Knight, stupidly brave but harmlessly insane. Had he always been that way? Who had he been when he was young and strong? Who did he love? How did Julian end up alone if the three of them, Julian, Beau, and Mags, were madly in love with each other?

On October 28, 2010, I was scrambling, trying to find something I could write, but my thoughts kept returning to the old man’s story. The innkeeper had referred to him as the Great Knight, stupidly brave but harmlessly insane. Had he always been that way? Who had he been when he was young and strong? Who did he love? How did Julian end up alone if the three of them, Julian, Beau, and Mags, were madly in love with each other?

What was their story? On November 1, I found myself keying the hokiest opening lines ever written, and from those lines emerged the story of an innkeeper, a bard, three mercenary knights, and the love triangle that covered fifty years of Julian’s life.

If I know how the story will end, I can build a plot to that point. This year, in November, I plan to finish a novel that has been on the back burner for five years.

I know how it will end because it is a historical sidenote in the Tower of Bones series. The story is canon because it has always been mentioned as a children’s story, the tale of an impossibly brave hero who does amazing and impossible things.

The novel separates Aelfrid-the-shaman from the myth of Aelfrid Firesword. It details both the founding of the Temple and the truth about Daryk, the rogue-mage who nearly destroyed it all.

I have written a synopsis of what I think will be the final chapters of Aelfrid’s story. It consists of two pages and is less than a thousand words. Each paragraph details a chapter’s events, and I’ve included a few words detailing my ideas for the characters’ moods and the general emotional atmosphere.

The way the final battle ends is canon. I have some notes, but I will choreograph the actual battle when I get to it. It is pivotal, but I won’t drag it out. I’ll show the crucial encounters and tell the minor ones, as I dislike reading drawn-out fight scenes and usually skip over them, just reading the high points.

So now, let’s go back and look at the place where the story begins. We want to focus on the day that changed everything because that is the moment we open the story.

I suggest writing a short synopsis of the story as you see it now. This will be as useful as an outline but isn’t as detailed. It will allow you to riff on each idea as it comes to you and is a great way to develop the storyline.

I suggest writing a short synopsis of the story as you see it now. This will be as useful as an outline but isn’t as detailed. It will allow you to riff on each idea as it comes to you and is a great way to develop the storyline.

Open the document and look at page one. Let’s put the protagonists in their familiar environment in the opening paragraphs. This chapter is the hook, the “Oh, my God! This happened to these nice people! chapter.” This chapter is where the author can hook or lose the reader.

How? We see the protagonist content in their life, or mostly so. A nice cup of tea might start the day, but by evening, a chain of events has begun. A stone has begun rolling downhill, the first incident that will become an avalanche of problems our protagonist must solve.

But how do we lose the reader when this is the most coolest, bestest story ever written?

When we are new in this craft, we have a burning desire to front-load the history of our characters into the story so the reader will know who they are and what the story is about.

Don’t do it.

Fortunately for me, my writers’ group is made up of industry professionals, and one in particular, Lee French, has an unerring eye for where the story a reader wants to know begins.

Fortunately for me, my writers’ group is made up of industry professionals, and one in particular, Lee French, has an unerring eye for where the story a reader wants to know begins.

I have to remind myself that the first draft is the thinking draft. In many ways, it’s a highly detailed outline, the document in which we build worlds, design characters, and forge relationships.

- The first draft, the November Novel, is the manuscript in which the story grows as we add to it.

We need a finite starting point, an incident of interest. If you’re like me, you have ideas for the ending, so you have a goal to write to. At this point, the middle of the story is murky, but it will come to you as you write toward the conclusion.

The inciting incident is the beginning because this is the point where all the essential characters are in one place and are introduced:

- The reader meets the antagonist and sees them in all their power.

- The protagonistknows one thing—the antagonist must be stopped. But how?

The story kicks into gear at the first pinch point because the protagonist’s comfortable existence is at risk.

What else will emerge over the following 60,000 or more words (lots more in my case)?

The protagonist will find this information out as the story progresses and only when they need to know it. With that knowledge, they will realize they’re doomed no matter what, but they’re filled with the determination that if they go down, they will take the enemy down, too.

The protagonist will find this information out as the story progresses and only when they need to know it. With that knowledge, they will realize they’re doomed no matter what, but they’re filled with the determination that if they go down, they will take the enemy down, too.

If you dump a bunch of history at the beginning, the reader has no reason to go any further. You have wasted words on something that doesn’t advance the plot and doesn’t intrigue the reader.

As you write, the people who will help our hapless protagonist will enter the story. They will arrive as they are needed. Each person will add information the reader wants, but only when the protagonist requires it. Some characters, people who can offer the most help, will be held back until the final half of the story.

We know how the story begins, and we know how it ends. The middle will write itself, and by the end of the novel, the reader will have acquired what they want to know.

With the last bits of information, the final pieces of the puzzle will fall into place. The promise of gaining all that knowledge is the carrot that keeps the reader involved in the book.

For the last #PrepTober installment, we will look at science and magic and why it’s important to start out knowing the rules for each.

I like to sit somewhere quiet and let my mind wander, picturing the place where the opening scene takes place.

I like to sit somewhere quiet and let my mind wander, picturing the place where the opening scene takes place. The novel I intend to finish this year is set at the end of the first millennium, while last year’s effort was set in the second century after the cataclysm canonically known as the Sundering of the Worlds. This means the world is very different. The forests and wildlife have had a thousand years to rebound, and while some areas are still struggling to recover, most of the west is lush in comparison.

The novel I intend to finish this year is set at the end of the first millennium, while last year’s effort was set in the second century after the cataclysm canonically known as the Sundering of the Worlds. This means the world is very different. The forests and wildlife have had a thousand years to rebound, and while some areas are still struggling to recover, most of the west is lush in comparison. I live only sixty-five miles north of Mount St. Helens, so I have a good local example of how things look after a devastating event. I also can see how flora and fauna rebound in the years following it.

I live only sixty-five miles north of Mount St. Helens, so I have a good local example of how things look after a devastating event. I also can see how flora and fauna rebound in the years following it.  When you create a fictional world, you create a culture. As a society, the habits we develop, the gods we worship, the things we create and find beautiful, and the foods we eat are products of our culture.

When you create a fictional world, you create a culture. As a society, the habits we develop, the gods we worship, the things we create and find beautiful, and the foods we eat are products of our culture. To show a world plausibly and without contradictions, we must consider how things work, whether it takes place in a medieval world or on a space station. Don’t introduce skills and tech that can’t exist or don’t fit the era.

To show a world plausibly and without contradictions, we must consider how things work, whether it takes place in a medieval world or on a space station. Don’t introduce skills and tech that can’t exist or don’t fit the era.  For instance, blacksmiths create and repair things made of metal. The equivalent of a medieval blacksmith on a space station will have high-tech tools and a different job title. Readers notice that sort of thing.

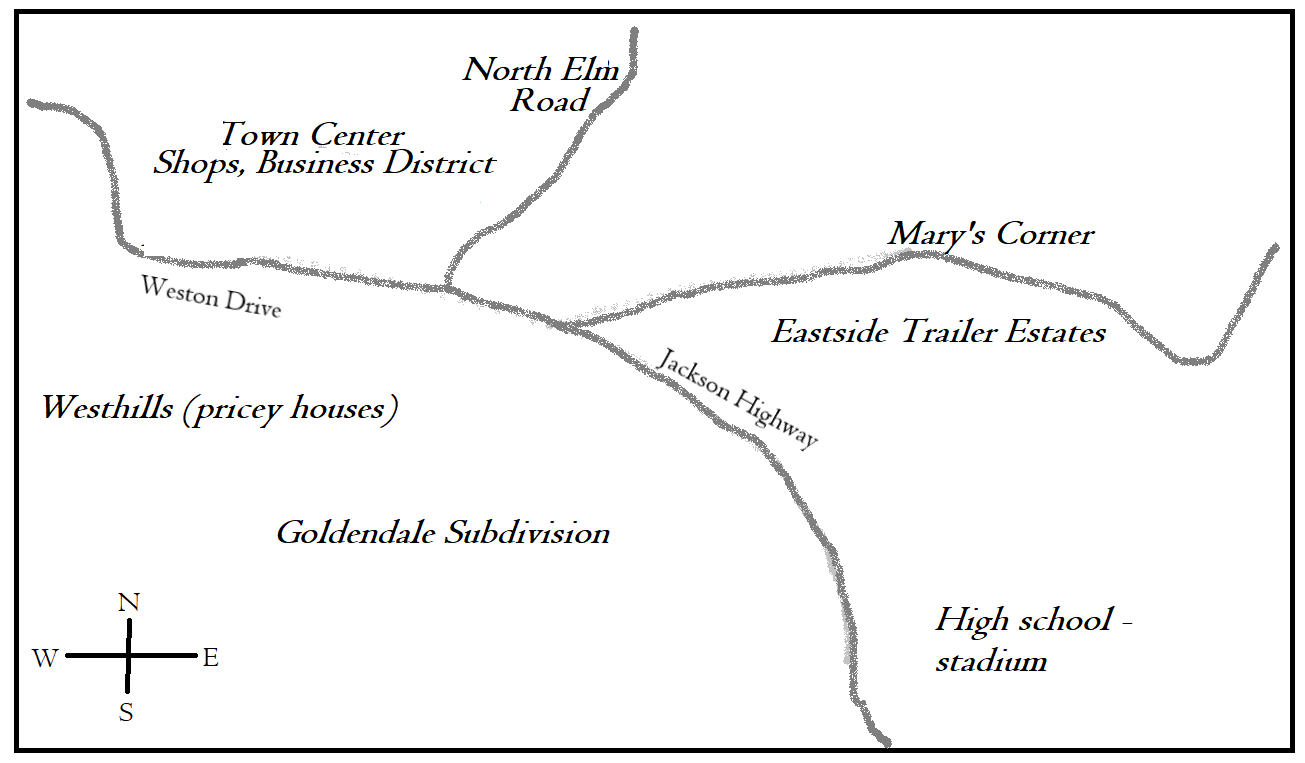

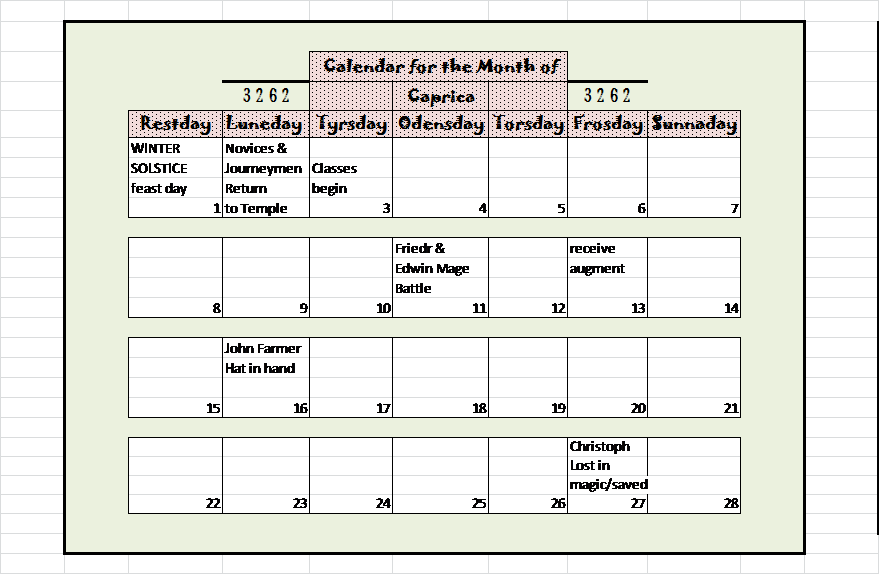

For instance, blacksmiths create and repair things made of metal. The equivalent of a medieval blacksmith on a space station will have high-tech tools and a different job title. Readers notice that sort of thing. A hand-scribbled map and a calendar of events are absolutely indispensable if your characters do any traveling. The map will help you visualize the terrain, and the calendar will keep events in a plausible order.

A hand-scribbled map and a calendar of events are absolutely indispensable if your characters do any traveling. The map will help you visualize the terrain, and the calendar will keep events in a plausible order.

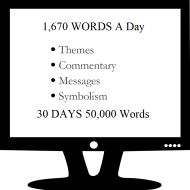

I was a dedicated municipal liaison for the Olympia, Washington Region for twelve years and a regular financial donor, but I walked away after the organization’s implosion last November. I will get my 50,000 new words in November but will not sign up to participate through the NaNoWriMo website.

I was a dedicated municipal liaison for the Olympia, Washington Region for twelve years and a regular financial donor, but I walked away after the organization’s implosion last November. I will get my 50,000 new words in November but will not sign up to participate through the NaNoWriMo website.

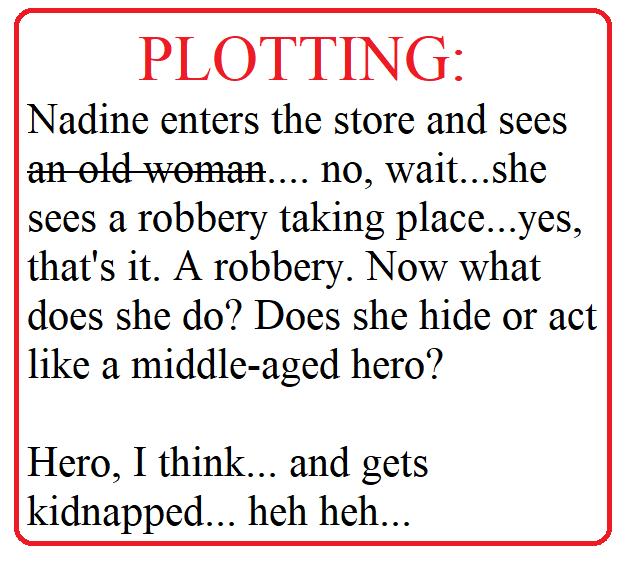

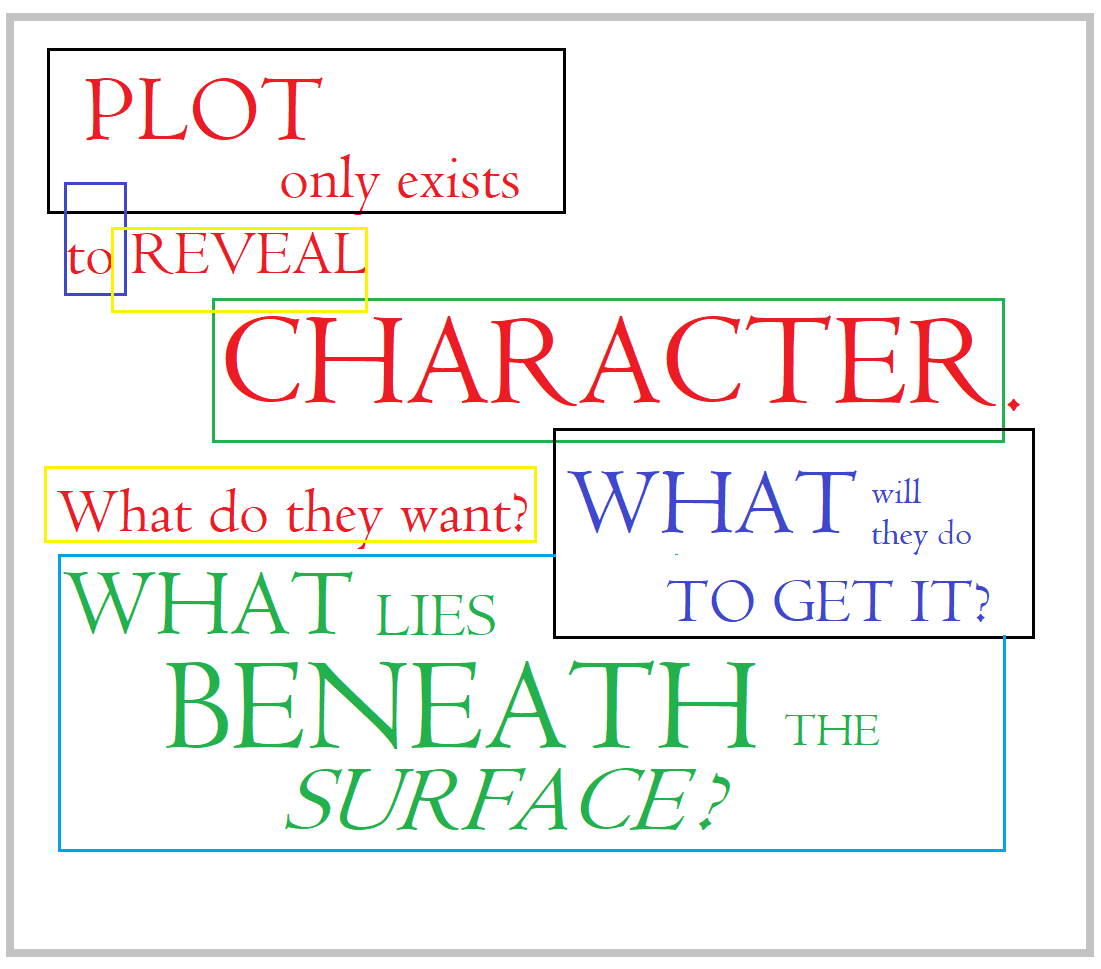

The answer to question number one kickstarts the plot: who are the players? Once I know the answer to this question, I can write, and write, and write … although most of what I write at that point will be background info. The answers to the other questions will emerge as I write the background blather.

The answer to question number one kickstarts the plot: who are the players? Once I know the answer to this question, I can write, and write, and write … although most of what I write at that point will be background info. The answers to the other questions will emerge as I write the background blather. They share some of their story the way strangers on a long bus ride might. I see the surface image they present to the world, but they keep most of their secrets close and don’t reveal all the dirt. These mysteries will be pried from them over the course of writing the narrative’s first draft.

They share some of their story the way strangers on a long bus ride might. I see the surface image they present to the world, but they keep most of their secrets close and don’t reveal all the dirt. These mysteries will be pried from them over the course of writing the narrative’s first draft. And what if you are writing poems or short stories? Graphic novels? We will also go into preparing to “speed-date your muse” when embarking on those aspects of writing.

And what if you are writing poems or short stories? Graphic novels? We will also go into preparing to “speed-date your muse” when embarking on those aspects of writing.

So, for the two final weeks of November and the first two weeks of December, we will be firing up the Starship Hydrangea (our hydrangea-blue Kia Soul) and driving 30 miles a day to and from the clinic. This will happen four out of five days a week, barring snow.

So, for the two final weeks of November and the first two weeks of December, we will be firing up the Starship Hydrangea (our hydrangea-blue Kia Soul) and driving 30 miles a day to and from the clinic. This will happen four out of five days a week, barring snow. I have no problem getting the first draft done with the aid of a pot of hot, black tea and a simple outline to keep me on track. All that’s required is for me to sit down for an hour or two each morning and write a minimum of 1667 words per day.

I have no problem getting the first draft done with the aid of a pot of hot, black tea and a simple outline to keep me on track. All that’s required is for me to sit down for an hour or two each morning and write a minimum of 1667 words per day. The real work begins after November. After writing most of a first draft, many people will realize they enjoy writing. Like me, they’ll be inspired to learn more about the craft. They discover that writing isn’t about getting a particular number of words written by a specific date, although that goal was a catalyst, the thing that got them moving.

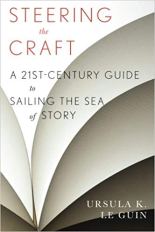

The real work begins after November. After writing most of a first draft, many people will realize they enjoy writing. Like me, they’ll be inspired to learn more about the craft. They discover that writing isn’t about getting a particular number of words written by a specific date, although that goal was a catalyst, the thing that got them moving. A good way to educate yourself is to attend seminars. By meeting and talking with other authors in various stages of their careers and learning from the pros, we develop the skills needed to write stories a reader will enjoy.

A good way to educate yourself is to attend seminars. By meeting and talking with other authors in various stages of their careers and learning from the pros, we develop the skills needed to write stories a reader will enjoy.

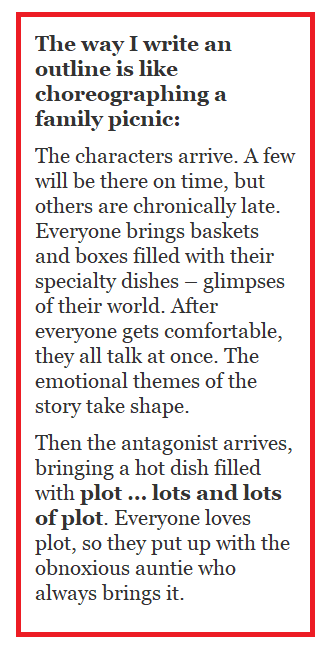

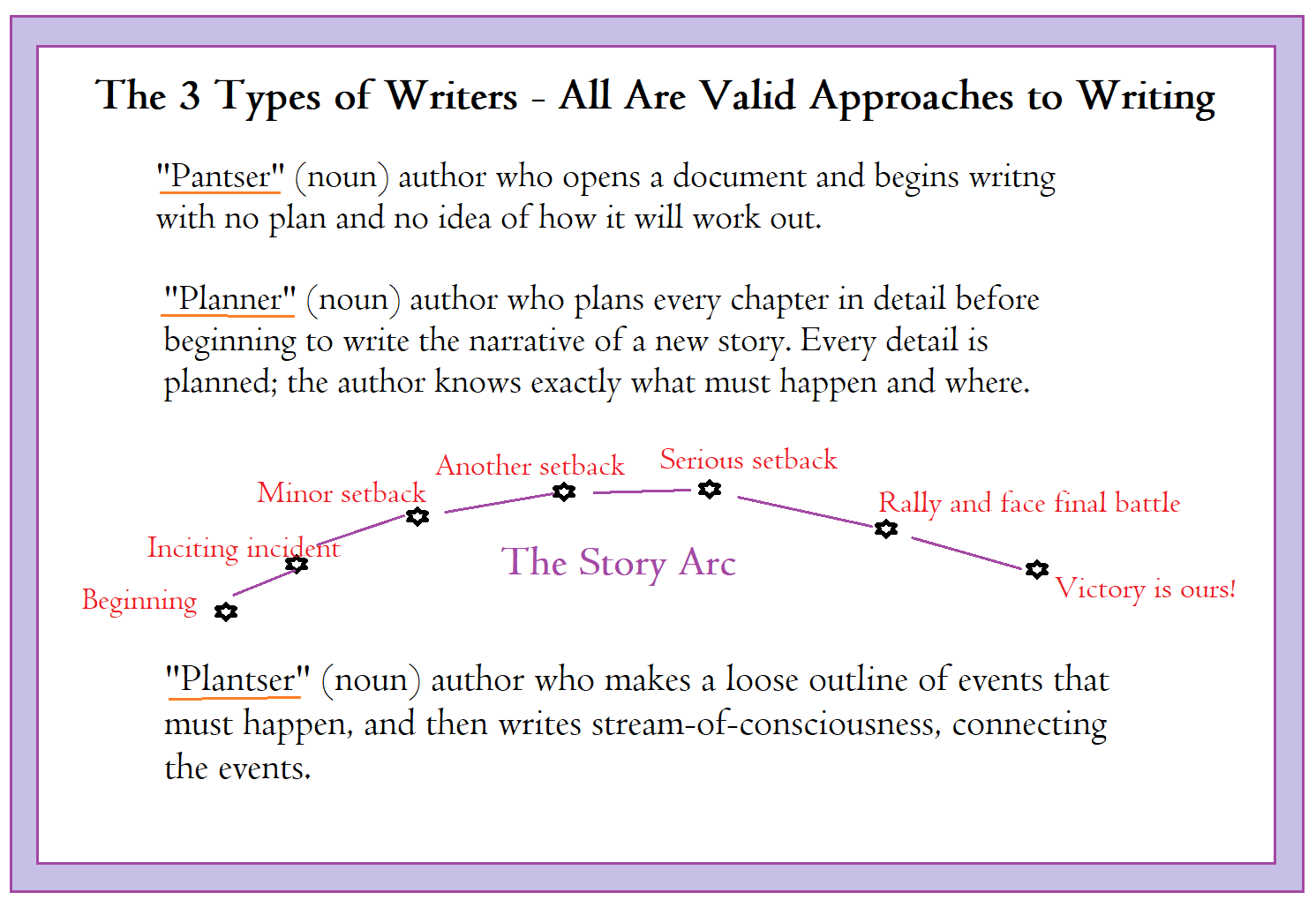

Pantser vs. Plotter

Pantser vs. Plotter  Planster

Planster