Today, we are revisiting the way our habitual word choices affect the pacing of our narrative.

We are encouraged to write active prose as opposed to passive, but what does that mean? First, the term “active prose” does not refer to the events that keep the plot arc moving.

We are encouraged to write active prose as opposed to passive, but what does that mean? First, the term “active prose” does not refer to the events that keep the plot arc moving.

Active prose refers to our word choices and how we construct our sentences.

A passive sentence is not “wrong.” No matter how active the phrasing, a poorly written sentence is not “better.”

Passive phrasing slows the reader’s perception of the story, which may be what you want.

- “Deep in the forest, there was a cabin.” Passive, descriptive, longer.

- “A cabin stood deep in the forest.” Active, verb forward, shorter.

The two examples say the same thing, but the words that surround and modify “cabin” change the mood of the sentence and set the tone for what follows. Neither sentence is right or wrong. It’s up to the writer to choose which style they go with.

Most modern readers don’t have the patience for long strings of descriptive, wordy sentences. However, they do like a chance to breathe and absorb what just happened.

Our task is to mingle active and passive phrasing to keep things balanced. That skill is a fundamental aspect of pacing.

Good pacing is about balanced prose as much as it is about staging the events. It is dynamic, engaging, and immersive.

How do we write balanced prose? It begins with the words we choose to show our story and the order in which we place them in the sentence.

The ways we combine active and passive phrasing are part of our signature, our voice. By mixing active phrasing with a little passive, we choose areas of emphasis and places in the narrative where we want to direct the reader’s attention.

The ways we combine active and passive phrasing are part of our signature, our voice. By mixing active phrasing with a little passive, we choose areas of emphasis and places in the narrative where we want to direct the reader’s attention.

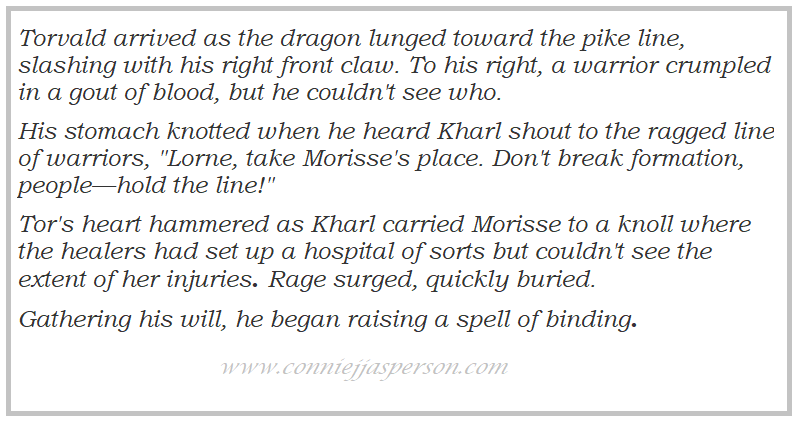

Some types of narratives should feel highly charged and action-packed. Most of your sentences should be constructed with the verbs forward if you write in genres such as sci-fi, political thrillers, and crime thrillers.

- Stephenie gripped the handhold, bracing herself.

The above sentence is Noun + verb + article + noun + transitive verb + noun.

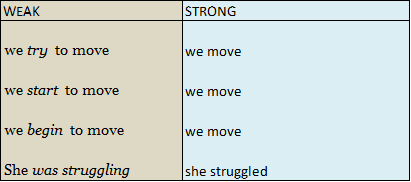

Verbs are action words, but all verbs are not equal in strength.

Verbs that begin with hard consonants are power verbs. They push the action outward from a character. Other verbs pull the action inward. The two forces, push and pull, create a sense of opposition and friction. Dynamism in word choices injects a passage with vitality, vigor, and energy.

- When we employ verbs that push the action outward from a character, we make them appear authoritative, competent, energetic, and decisive.

- Conversely, verbs that pull the action in toward the character make them appear receptive, attentive, private, and flexible.

A poor choice of words makes a sentence weak. Passive construction can still be strong despite being poetic.

A poor choice of words makes a sentence weak. Passive construction can still be strong despite being poetic.

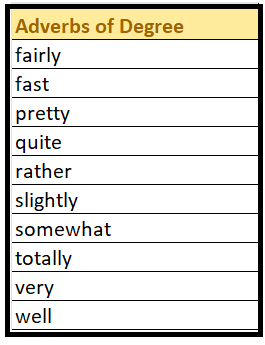

Has someone said your work is too wordy? An excess of modifiers could be the offenders.

- Look for the many forms of the phrasal verb to be. These words easily connect to other words and lead to long, convoluted passages.

- Look for connecting modifiers (still, however, again, etc.).

Concise writing can be difficult for those of us who love words in all their glory. Nevertheless, I work at it.

My goal during revisions is to make use of contrasts to show the story with the least number of words.

- dwell on / ignore

- embrace / reject

- consent / refuse

- agony / ecstasy

Many power words begin with hard consonants. The following is a short list of nouns and adjectives that start with the letter B. The images they convey when used to describe action project a feeling of power:

- Backlash (noun)

- Beating (noun or verb)

- Beware (verb)

- Blinded (adjective)

- Blood (noun)

- Bloodbath (noun)

- Bloodcurdling (adjective)

- Bloody (adjective)

- Blunder (noun or verb)

As you can see, some nouns are also verbs, such as beating or blunder. When you incorporate any of the above “B” words into your prose, you are posting a road sign for the reader, a notice that danger lies ahead.

If I want to create an atmosphere of anxiety, I would use words that push the action outward:

- Agony (noun)

- Apocalypse (noun)

- Armageddon (noun)

- Assault (verb)

- Backlash (noun)

- Pale (modifier)

- Panic (verb or noun)

- Target (verb)

- Teeter (verb)

- Terrorize (verb)

If I want to show the interior workings of a character without resorting to a dump of italicized whining, I could write their internal observations using words that draw us in:

- Delirious (modifier)

- Depraved (modifier)

- Desire (verb)

- Dirty (modifier)

- Divine (modifier)

- Ecstatic (modifier)

So why are verbs so crucial in shaping the tone and atmosphere of a narrative? When things get tricky and the characters are working their way through a problem, verbs like stumble or blunder offer a sense of chaos and don’t require a lot of modifiers to show the atmosphere.

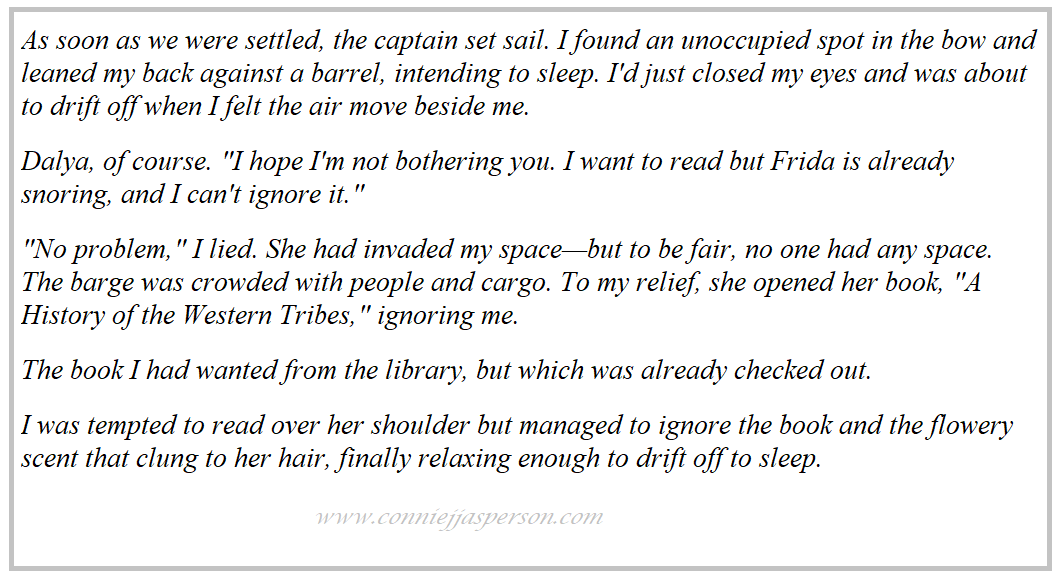

We are drawn to the work of our favorite authors because we like their voice and writing style. The unique, recognizable way they choose words and assemble them into sentences appeals to us, although we don’t consciously think of it that way.

We are drawn to the work of our favorite authors because we like their voice and writing style. The unique, recognizable way they choose words and assemble them into sentences appeals to us, although we don’t consciously think of it that way.

In the second draft, I finetune the plot arc and character arcs, and most importantly, I adjust phrasing.

The tricky part is catching all the weak word choices. Those of you who write a clean first draft are rare and wonderful treasures. I wish I had that talent.

When I find a stretch of blah-blah-blah, I reimagine the scene. I go to the thesaurus to see how to strengthen the narrative while still keeping to my original intention.

There are times when nothing will improve an awkward scene, and it must be scrapped. Be brave and be bold, and cut away the dead wood.

Things to remember:

- Where we choose to place the verbs changes their impact but not their meaning.

- The words we surround verbs with change the mood but not their intention.

- Modifiers are words that alter their sentences’ meanings. They add details and clarify facts, distinguishing between people, events, or objects.

- Infinitives are mushy words, words with no definite beginning or end.

Modifiers and infinitives are necessary for good writing. However, like salt or any other seasoning, they have the power to strengthen or weaken our prose.

So now you know what I have been doing here at Casa del Jasperson. Cleaning up my excessively wordy work-in-progress is time-consuming. However, I enjoy this aspect of the craft as much as writing the first draft.

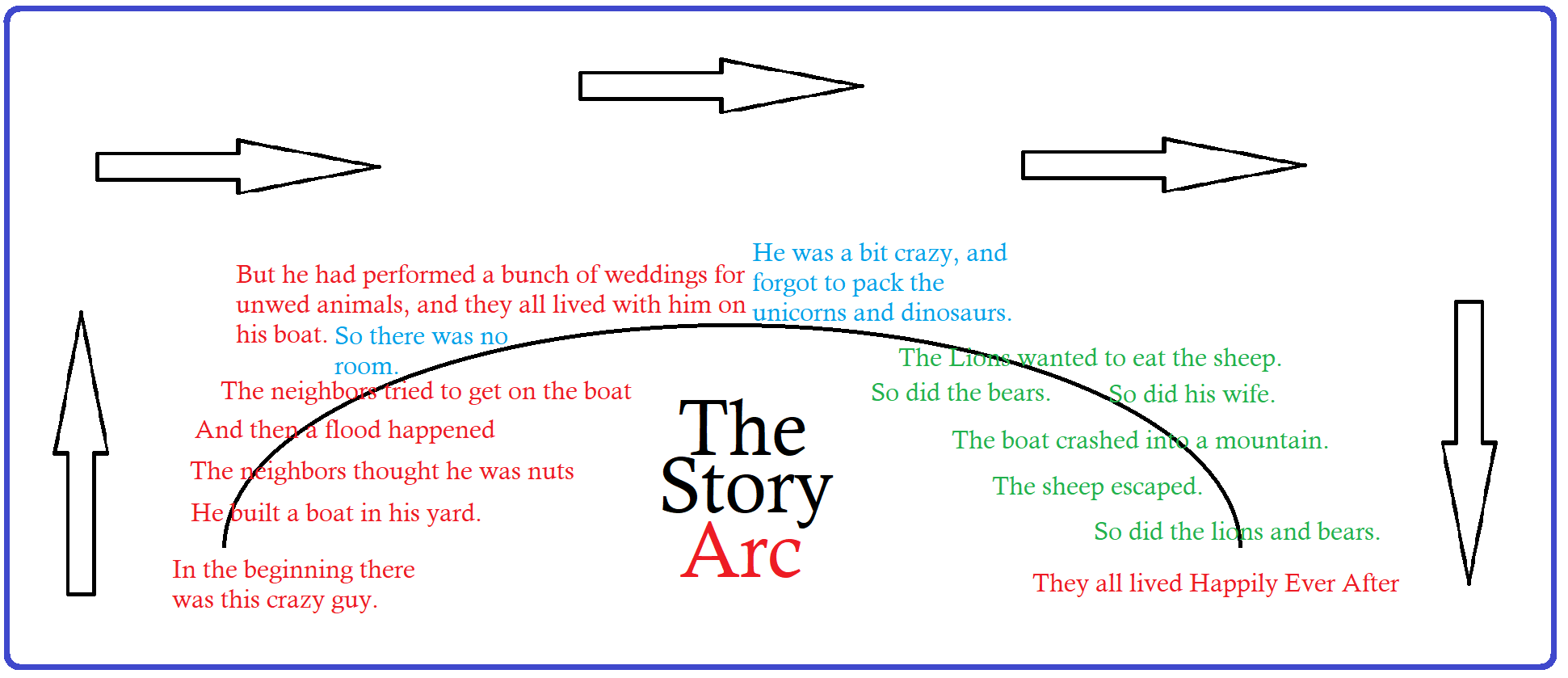

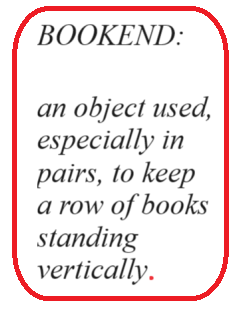

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next.

The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next. We forget to consider how the action affects both the protagonist and the reader. The reader needs a small break between incidents to process what just happened, and the characters need a chance to regroup and make plans.

We forget to consider how the action affects both the protagonist and the reader. The reader needs a small break between incidents to process what just happened, and the characters need a chance to regroup and make plans. Stories are a balancing act detailing the lives of engaging characters having intriguing and believable adventures. The reader lives and processes the action as it happens, suspending their disbelief.

Stories are a balancing act detailing the lives of engaging characters having intriguing and believable adventures. The reader lives and processes the action as it happens, suspending their disbelief. But if you are writing genre fiction, the market you are writing for expects more action than introspection. These stories are also character-driven, but the adventure, how the protagonist meets and overcomes the battles and roadblocks, is what interests the reader.

But if you are writing genre fiction, the market you are writing for expects more action than introspection. These stories are also character-driven, but the adventure, how the protagonist meets and overcomes the battles and roadblocks, is what interests the reader. Conversations illuminate a group’s relationship with each other and sheds light on our characters’ fears. It shows that they are self-aware and should present information not previously discussed.

Conversations illuminate a group’s relationship with each other and sheds light on our characters’ fears. It shows that they are self-aware and should present information not previously discussed. Great characters begin in an unfinished state, a pencil sketch, as it were. They emerge from the events of their journey in full color, fully realized in the multi-dimensional form in which you initially visualized them.

Great characters begin in an unfinished state, a pencil sketch, as it were. They emerge from the events of their journey in full color, fully realized in the multi-dimensional form in which you initially visualized them. I have “pantsed it” occasionally, which can be liberating but for me, there always comes a point where I realize my manuscript has gone way off track and is no longer fun to write. Then I must return to the point where the story stopped working and make an outline.

I have “pantsed it” occasionally, which can be liberating but for me, there always comes a point where I realize my manuscript has gone way off track and is no longer fun to write. Then I must return to the point where the story stopped working and make an outline. At first, the page is only a list of headings that detail the events I must write for each chapter. I know what end I have to arrive at. But the chapter headings are pulled out of the ether, accompanied by the howling of demons as I force my plot to take shape:

At first, the page is only a list of headings that detail the events I must write for each chapter. I know what end I have to arrive at. But the chapter headings are pulled out of the ether, accompanied by the howling of demons as I force my plot to take shape: Don’t be afraid to rewrite what isn’t working. Save everything you cut because I guarantee you will want to reuse some of that prose later at a place where it makes more sense.

Don’t be afraid to rewrite what isn’t working. Save everything you cut because I guarantee you will want to reuse some of that prose later at a place where it makes more sense.

Some novels are character-driven, others are event-driven, but all follow an arc. I’m a poet, and while I read in every genre, I seek out literary fantasy, novels with a character-driven plot. These are works by authors like

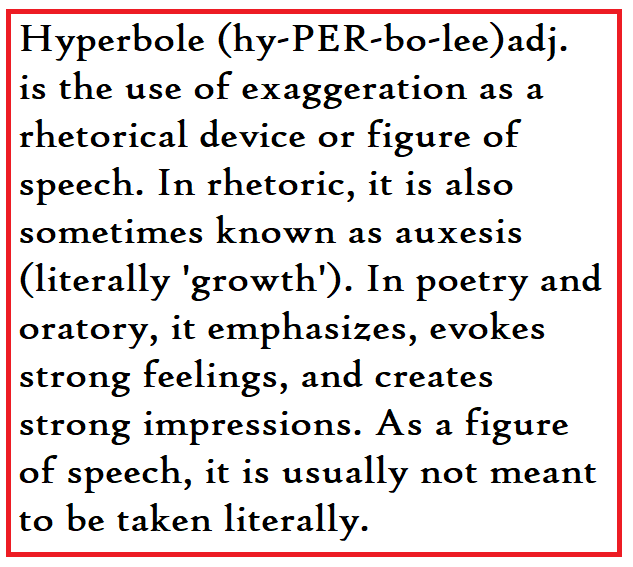

Some novels are character-driven, others are event-driven, but all follow an arc. I’m a poet, and while I read in every genre, I seek out literary fantasy, novels with a character-driven plot. These are works by authors like  And the prose … words with impact, words combined with other words, set down in such a way that I feel silly even thinking I can write such works. Thankfully, my editor weeds out pretentious hyperbole and slaps me back to reality.

And the prose … words with impact, words combined with other words, set down in such a way that I feel silly even thinking I can write such works. Thankfully, my editor weeds out pretentious hyperbole and slaps me back to reality. This emotional low point is necessary for our characters’ personal arcs. It is the place where they are forced to face their weaknesses and rebuild themselves. They must discover they are stronger than they ever knew.

This emotional low point is necessary for our characters’ personal arcs. It is the place where they are forced to face their weaknesses and rebuild themselves. They must discover they are stronger than they ever knew. When we commit to writing daily, our writing style grows and changes. When I began writing, some chapters totaled over 4,000 words.

When we commit to writing daily, our writing style grows and changes. When I began writing, some chapters totaled over 4,000 words. As a reader, books work best for me when each chapter details the events of one large scene or several related events. I think of chapters as if they were paragraphs. Paragraphs are not just short blocks of randomly assembled sentences.

As a reader, books work best for me when each chapter details the events of one large scene or several related events. I think of chapters as if they were paragraphs. Paragraphs are not just short blocks of randomly assembled sentences. I’ve mentioned before that one of the complaints some readers have with

I’ve mentioned before that one of the complaints some readers have with  Short stories run up to 7,000 words, with under 4,000 being the most commonly requested length. 7,500–17,500 is the expected length for novelettes, and between 17,500 and 40,000 words are the standard length for novellas.

Short stories run up to 7,000 words, with under 4,000 being the most commonly requested length. 7,500–17,500 is the expected length for novelettes, and between 17,500 and 40,000 words are the standard length for novellas. However, (cue the danger theme music), once I have set it aside for a while, I will have to begin the revision process. That is when writing becomes work. This is the moment I discover the child of my heart isn’t perfect – my action scenes are a little … confusing.

However, (cue the danger theme music), once I have set it aside for a while, I will have to begin the revision process. That is when writing becomes work. This is the moment I discover the child of my heart isn’t perfect – my action scenes are a little … confusing.