We are approaching the last days of NaNoWriMo 2022. If you haven’t already, now is an excellent time to think about creating what I think is the most helpful tool in my toolbox—the stylesheet.

When a manuscript comes across their desk, editors and publishers create a list of names, places, created words, and other things that may be repeated and pertain only to that manuscript. This is called a stylesheet.

When a manuscript comes across their desk, editors and publishers create a list of names, places, created words, and other things that may be repeated and pertain only to that manuscript. This is called a stylesheet.

The stylesheet can take several forms, but it is only a visual guide to print out or keep minimized until needed. Some editors refer to it as a “bible.” Sometimes it will be called a storyboard if it also contains plot ideas or an outline.

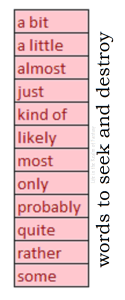

Nowadays, I make a new stylesheet at the outset of each writing project, even for short stories. I copy and paste every new word or name onto my list, doing this the first time they appear in the manuscript. This is an essential tool because if each name, place name, and made-up word is listed the way I originally intended, I’ll be less likely to inadvertently contradict myself later on in the tale.

Some people use a program called Scrivener, which is not too expensive, but which has a tricky learning curve. I couldn’t make heads or tails of it and found it quite frustrating. Nevertheless, I understand that it works well for many people, and you might find it works for you.

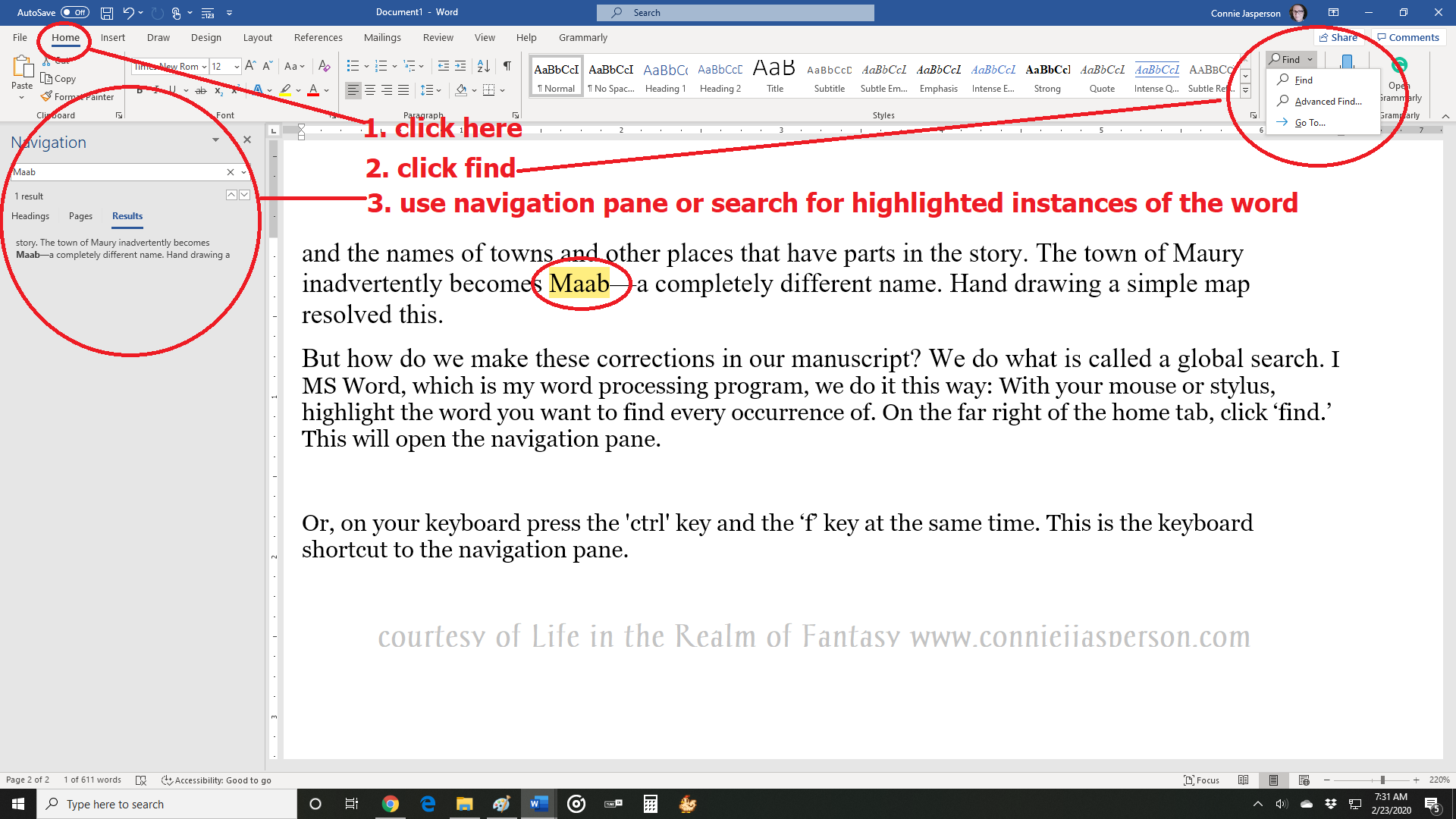

Myself, I don’t want a fancy word-processing program. I use MS Office because I have been using the programs that come with that software since 1993, and I’ve been able to adapt to each upgrade they have made. It’s affordable, so I use Word to write and edit in and Excel to create stylesheets.

For short stories, the stylesheet will probably be a Word document. I have written them out by hand on occasion. You can create them in Google Sheets or Docs, which is free.

For short stories, the stylesheet will probably be a Word document. I have written them out by hand on occasion. You can create them in Google Sheets or Docs, which is free.

And free is good! Everyone thinks differently, so there is no single perfect way that fits everyone.

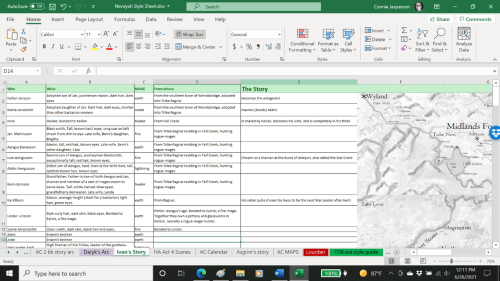

In Excel, the storyboard for my ideas works this way:

At the Top of page one: I give the piece a working title.

When I have an idea for a short story, I include the intended publication and closing date for submissions (not needed if it’s for a novel). I make a note of the intended word count. Having a word count limit keeps me alert for unnecessary backstory. For most publications, you must keep strictly within their word count requirements.

Page one of the workbook contains the personnel files.

Column A: Character Names. I list the essential characters by name and the critical places where the story will be set.

Column B: About: What their role is, a note about that person or place, a brief description of who and what they are.

Column C: The Problem: What is the core conflict?

Column D: What do they want? What does each character desire?

Column E: What will they do to get it? How far will they go to achieve their desire?

Page Two: The projected story arc will be on page two of the workbook. I list each chapter by the events that need to be resolved at various points in the manuscript.

Page Two: The projected story arc will be on page two of the workbook. I list each chapter by the events that need to be resolved at various points in the manuscript.

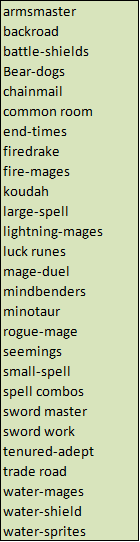

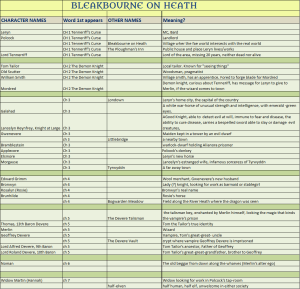

Page three of the workbook is the most important—the Glossary. This list of made-up words, names, and places is crucial for the finished product. The way words appear on this list is how they should occur throughout the entire story or novel. This page ensures consistency and keeps the spellings from drifting as I lay down prose in the first draft.

I update the glossary page whenever a word or name is added or changed. I do this even in my non-fantasy work, as it helps to have a quick, easy-to-access reminder of how real-world names and places are spelled.

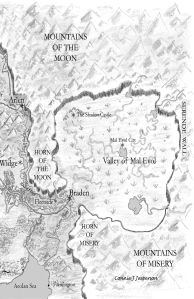

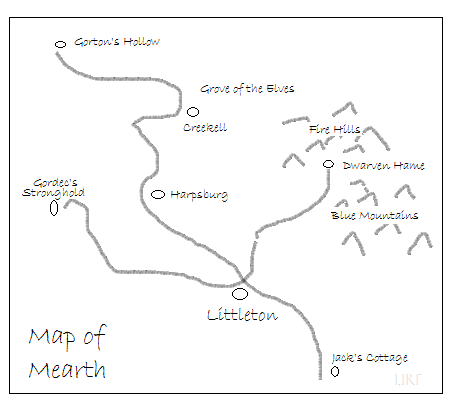

Page four will have maps and a calendar for that world. The calendar is a central tool that keeps the events happening logically.

The workbook shown below is the stylesheet for the Tower of Bones series and has been evolving since 2009. It has grown since this screenshot was taken.

We never really know how a story will go, even if we begin with a plan. We will probably deviate some from the original outline. Usually, for me, the major events will remain as they were plotted in advance, even though side themes will evolve. The outline keeps me on track with length and ensures the action doesn’t stall.

We never really know how a story will go, even if we begin with a plan. We will probably deviate some from the original outline. Usually, for me, the major events will remain as they were plotted in advance, even though side themes will evolve. The outline keeps me on track with length and ensures the action doesn’t stall.

When I know the length of a book or story I intend to write, I know how many words each act should be and how many scenes/chapters I need to devote to that section. I like to keep my chapters at around 1600 – 2000 words. Sometimes they go longer, and other times shorter.

The plot usually evolves as I write each event and connect the dots. In one instance, it was completely changed. The original plot didn’t work at all, so drastic measures had to be taken.

The plot usually evolves as I write each event and connect the dots. In one instance, it was completely changed. The original plot didn’t work at all, so drastic measures had to be taken.

Making that course correction was less work because I had the stylesheet with the outline. Events were easy to cut and replace or move along the timeline.

As we near the end of NaNoWriMo, we are beginning to dig deeper into all aspects of the story. We’re still writing the basic first draft, but emotions, both expressed and unexpressed, are growing more apparent.

Secrets characters have withheld from us emerge now as we write. Perhaps some ugly truths have been discovered. These details arise as I write, reshaping how the characters react to each other. In turn, these interactions can alter the plot.

Even though each manuscript starts out linearly, I work “back and forth” when writing rather than in a linear fashion. I work from an outline, but each section of my novel is written when I am inspired to work on that part of the tale.

The central plot points get written first. Then, I write connecting scenes to ‘stitch’ the sections together when the draft is complete, like assembling a quilt.

A detailed outline ensures I won’t get lost in the weeds of wacky side quests.

Once the first draft is finished, revisions will mean updating the stylesheet, but that’s part of the job. This ensures my editor will have less work when we get to the final draft.

Once the first draft is finished, revisions will mean updating the stylesheet, but that’s part of the job. This ensures my editor will have less work when we get to the final draft.

In the process of editing for me, Irene will find things that didn’t get listed but should have been and will update the stylesheet.

Writing a novel is a process of growth and development. It doesn’t stop until you sign off on the proof copies and the book is on sale.

And even then, you will think of things you could have done differently.

The plan or design is submitted to the client, who likes it. A mockup of the first iteration is submitted to the client, who still likes it, but … their needs have changed a little, and a new adjustment must be incorporated.

The plan or design is submitted to the client, who likes it. A mockup of the first iteration is submitted to the client, who still likes it, but … their needs have changed a little, and a new adjustment must be incorporated. Books are one area where project creep is not only appreciated but encouraged. Stories are particularly prone to this continual expansion of the original ideas. Short stories grow into novellas and then into novels, becoming a series of books.

Books are one area where project creep is not only appreciated but encouraged. Stories are particularly prone to this continual expansion of the original ideas. Short stories grow into novellas and then into novels, becoming a series of books. The first aspect of this is to Identify your Project Goals – create a rudimentary outline with names, who they are in relation to the protagonist, and decide who is telling the story. Remember, your story is your invention. Some inventions are in development for years before they get to market. Others are complete and ready to market in a relatively short time. Regardless of your production timeline, this is where project management skills really come into play.

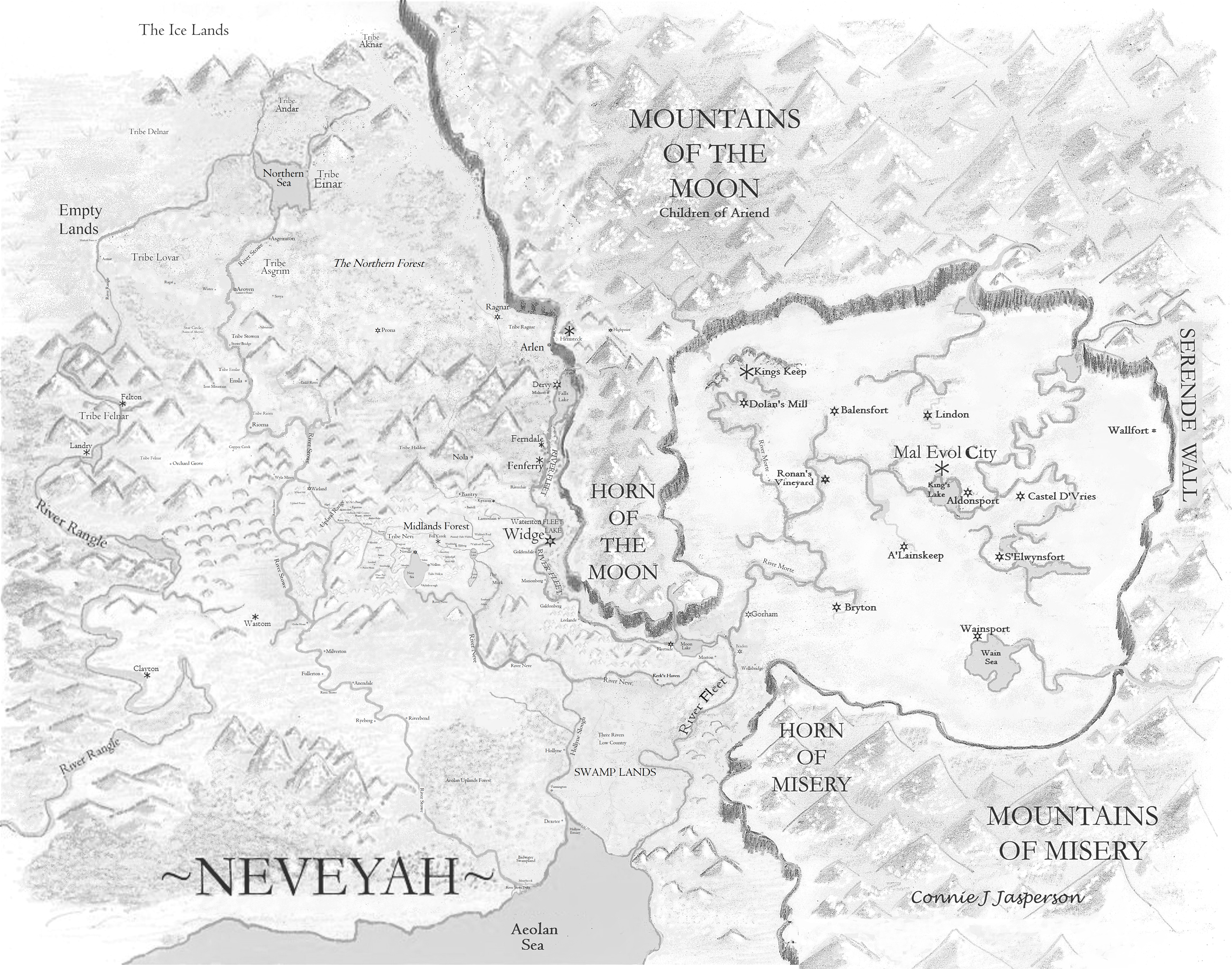

The first aspect of this is to Identify your Project Goals – create a rudimentary outline with names, who they are in relation to the protagonist, and decide who is telling the story. Remember, your story is your invention. Some inventions are in development for years before they get to market. Others are complete and ready to market in a relatively short time. Regardless of your production timeline, this is where project management skills really come into play. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy – all you need are some lines and scribbles telling you all the essential things, like which direction is north and what certain towns are named. Use a pencil, to easily update your map if something changes during revisions.

Your map doesn’t have to be fancy – all you need are some lines and scribbles telling you all the essential things, like which direction is north and what certain towns are named. Use a pencil, to easily update your map if something changes during revisions. Time can get a little mushy when we are winging it through a manuscript. A calendar gives us a realistic view of how long it takes to travel from point A to point B, or how much time it will take to complete a task.

Time can get a little mushy when we are winging it through a manuscript. A calendar gives us a realistic view of how long it takes to travel from point A to point B, or how much time it will take to complete a task. This month of concentrated writing time is meant to help authors get the entire story down while the inspiration and ideas are flowing. At the end of the thirty days, you should have a novel-length story, hopefully with a complete story arc (beginning, middle, and end).

This month of concentrated writing time is meant to help authors get the entire story down while the inspiration and ideas are flowing. At the end of the thirty days, you should have a novel-length story, hopefully with a complete story arc (beginning, middle, and end). First, we want to get to know who we’re writing about.

First, we want to get to know who we’re writing about. Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as stronger than one whose name begins with a soft sound. It’s a little thing but is something to consider when trying to convey personalities.

Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as stronger than one whose name begins with a soft sound. It’s a little thing but is something to consider when trying to convey personalities. If you need ideas for showing a variety of emotions, I highly recommend the

If you need ideas for showing a variety of emotions, I highly recommend the  Some people use a program called Scrivener, which is not too expensive, but which I found quite frustrating. Nevertheless, I understand that it works well for many people, so it may be an investment to consider.

Some people use a program called Scrivener, which is not too expensive, but which I found quite frustrating. Nevertheless, I understand that it works well for many people, so it may be an investment to consider. Maps are essential tools when you are building the world. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. You need to know north, south, east, west, where rivers and forests are relative to towns, and locations of mountains.

Maps are essential tools when you are building the world. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. You need to know north, south, east, west, where rivers and forests are relative to towns, and locations of mountains.

And we’ll just toss this out there – while you can drop a tall tree across a narrow creek, building bridges over rivers requires a certain amount of engineering. Cultures from the Stone Age on to modern times have had the skills needed to make bridges.

And we’ll just toss this out there – while you can drop a tall tree across a narrow creek, building bridges over rivers requires a certain amount of engineering. Cultures from the Stone Age on to modern times have had the skills needed to make bridges.