If you read last week’s post, you know that I am working on both the hero and villain of my work-in-progress.

And now that it is December, I can expand on each character’s theme, a sub-thread that is solely theirs. A personal theme can shape how each character reacts and interacts throughout the narrative. The themes were established in the first book, but they (and the characters) will evolve as the story does.

And now that it is December, I can expand on each character’s theme, a sub-thread that is solely theirs. A personal theme can shape how each character reacts and interacts throughout the narrative. The themes were established in the first book, but they (and the characters) will evolve as the story does.

Themes emphasize the motivations of our characters and underscore both strengths and weaknesses.

For example, a villain’s personal theme might be hubris (excessive self-confidence). It can also be a hero’s theme. It is a high degree of arrogance, and terrible decisions can arise from it.

A hero’s personal theme might be honor and loyalty. This might also be their weakness, as it can undermine their ability to act decisively. In trying to save someone she desperately loves, others might suffer. In Star Trek terms, the good of the one can exceed the good of the many, and people will die that could have been saved. Who is the villain in that case?

Sometimes, there is little distinction between heroes and villains in real life. Some heroes are jackasses who need to be taken down a notch. Some villains will extort protection money from a store owner and then turn around and open a soup kitchen to feed the unemployed.

Al Capone famously did just that. Mobster Al Capone Ran a Soup Kitchen During the Great Depression – HISTORY.

In reality, heroes are flawed because no one is perfect. So, don’t be too shocked and heartbroken when a public figure you admire is discovered to have personal failings. Most of the time, those failings are only a small part of their character, as we hope our own weaknesses are.

In reality, heroes are flawed because no one is perfect. So, don’t be too shocked and heartbroken when a public figure you admire is discovered to have personal failings. Most of the time, those failings are only a small part of their character, as we hope our own weaknesses are.

When I first designed my characters, I assigned them verbs, nouns, and adjectives, traits they embody. They must also have a void, an emotional emptiness, a wound of some sort.

The void is necessary because characters must overcome personal cowardice to face it. As a reader, I’ve noticed that my favorite characters each have a hint of self-deception. All the characters deceive themselves about their own motives.

The heroes we admire eventually recognize their flaws and become stronger, able to do what is necessary. The villains may also acknowledge their fatal flaw but use it to justify and empower their actions.

I like heroes and villains with possibilities. I like believing that the villain might be redeemed, or the hero might become the villain.

That is why in my current work, the tragic hero who becomes the villain is central to my story. In other stories, I have explored the broken hero, the one who rises from the ruins of their life to save the day. So, it just seemed right to consider a hero who fights with all his heart but for the wrong side.

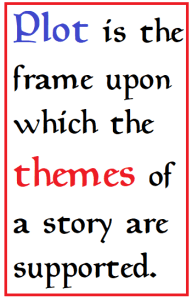

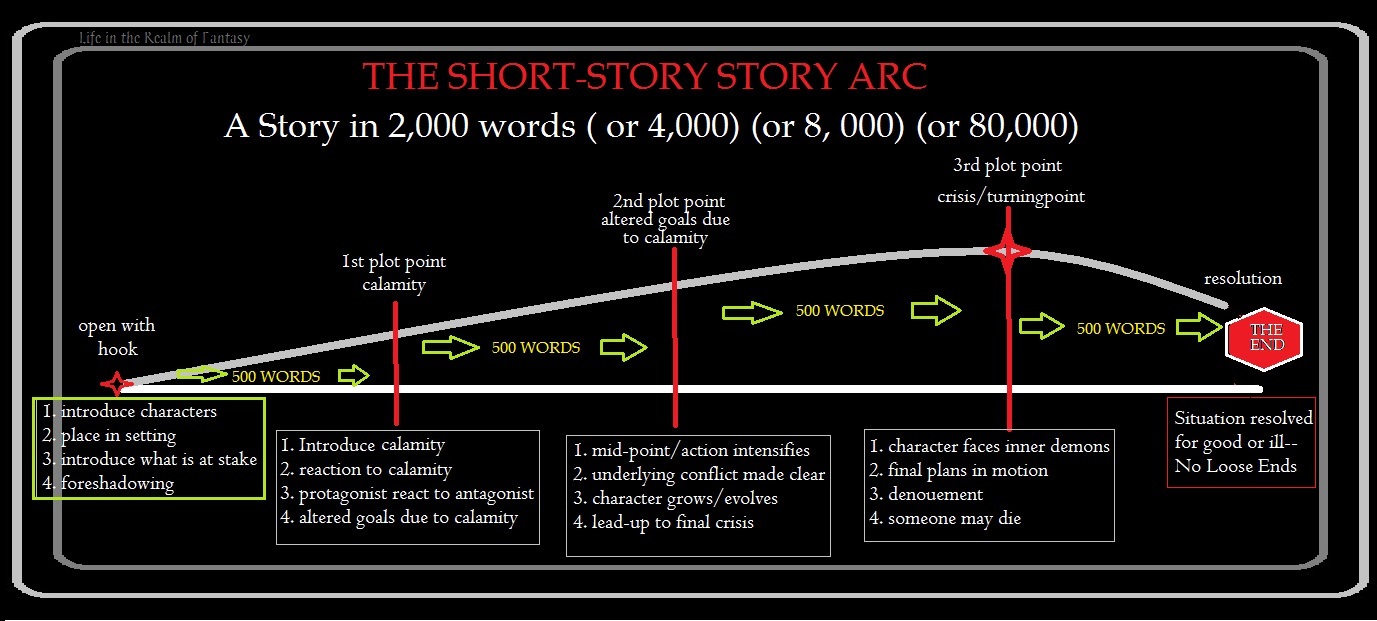

My creative mind works by having plots and characters evolve together. When I sit down to create a story arc, my characters offer hints about how they will develop. Themes emerge, and their evolution can alter the course of different character arcs.

Who in your work will be best suited to play the villain? Character B?

Conversely, why is character A the hero?

In the early stages of a first draft, I know who the hero and the antagonist are. But until I know who they are when they are off duty and enjoying their downtime, I don’t really know them.

In the early stages of a first draft, I know who the hero and the antagonist are. But until I know who they are when they are off duty and enjoying their downtime, I don’t really know them.

No matter what genre we write in, when we design the story, we build it around a need that must be fulfilled, a quest of some sort. The story needs a theme, each character needs a theme, and once I know what those themes are, I will have the heart of it.

Of course, for my protagonist, the quest to unite his world is the primary goal. But he has secrets, underlying motives not explicitly stated at the outset. There is a theme to those secrets. The same goes for my villain.

Now that I am building the second half of the story, my supporting characters also have agendas that conflict with the hero’s. Their role in that story is affected by their personal ambitions and desires. My hero’s first quest is to get them to shed their xenophobia.

The antagonists also have motives, both stated and unstated. They need to thwart the protagonist and must have a logical reason for doing so. They have a history that goes beyond the obvious “they needed a bad guy, and I’m it” of the cartoon villain.

No one goes through life acting on impulses for no reason whatsoever. On the surface, an action may seem random and mindless. The person involved might claim there was no reason or even be accused of it, but that is a fallacy, a lame excuse they might offer to conceal the secret that really drives them.

Half of this story is written and will not be published as a novel until its sequel is ready for publication. I can see the whole story, but the details are blurry. So, I have an idea of what the entire story will be. And now as I write, the second half of this story unfolds.

As a reader, I dislike discovering the author doesn’t really know how to get what their protagonist wants. I always have the urge to tell them that a working relationship with a trusted editor could have helped a great deal. A strong personal theme would help identify what each character needs and wants. Random events inserted to keep things interesting don’t advance the story. But motivation does, and using themes can lead the writer to it.

As a reader, I dislike discovering the author doesn’t really know how to get what their protagonist wants. I always have the urge to tell them that a working relationship with a trusted editor could have helped a great deal. A strong personal theme would help identify what each character needs and wants. Random events inserted to keep things interesting don’t advance the story. But motivation does, and using themes can lead the writer to it.

Character creation crosses all genres. I write fantasy, but even if you are writing a memoir detailing your childhood, the basics of story telling come into play. You are telling a story about the person you were in those days. What were the themes that bound your experiences together? You want the reader to see the events that shaped you, not through the lens of memory, but as if they were observing them unfold.

No matter the genre you write in, some things are universal. Who are your characters? Who do they love, and who do they despise? How can a strong personal theme emphasize a character’s personality?

I hope your work is progressing well. In the darkness of December, the Christmas lights decorating the apartment building across the way cheer me up. They make the eternal Northwest rain seem less oppressive.

My favorite comfort foods and a cup of tea make for cozy evenings spent thinking about how I want this plot to go. Writing is hard work, but it’s good work.

Writing groups can be quite different in their areas of focus. Some are critique groups, and some are more support groups. No matter what the group focuses on in its meetings, the anthology is meant to showcase that group’s professionalism.

Writing groups can be quite different in their areas of focus. Some are critique groups, and some are more support groups. No matter what the group focuses on in its meetings, the anthology is meant to showcase that group’s professionalism. “Your best work” gets off to a great start when the story is written with the central theme of the anthology in mind, a central facet of the story.

“Your best work” gets off to a great start when the story is written with the central theme of the anthology in mind, a central facet of the story. The editors have said that one can face the reality of the past, present, or future—it’s up to each author to write their story. We must find ways to layer that theme into the character arcs, plot, and world building.

The editors have said that one can face the reality of the past, present, or future—it’s up to each author to write their story. We must find ways to layer that theme into the character arcs, plot, and world building. Basically, his guidelines say you must use Times New Roman (or sometimes Courier) .12 font. You must also ensure your manuscript is formatted as follows:

Basically, his guidelines say you must use Times New Roman (or sometimes Courier) .12 font. You must also ensure your manuscript is formatted as follows: The editor of the anthology has posted a public call for the best work that authors can provide, and they will receive a landslide of submissions. They will receive far more stories than they will have room for, and the majority of them will be memorable, wonderful stories.

The editor of the anthology has posted a public call for the best work that authors can provide, and they will receive a landslide of submissions. They will receive far more stories than they will have room for, and the majority of them will be memorable, wonderful stories. So, let’s take a look at theme, the thread that binds emotions and points of no return together. It’s time to take another look at how

So, let’s take a look at theme, the thread that binds emotions and points of no return together. It’s time to take another look at how  Saunders gives us the character of Ray Abnesti, a scientist developing pharmaceuticals and using convicted felons as guinea pigs as part of the justice system. The wider world has forgotten about those whose crimes deserve punishment, whose fate goes unknown and unlamented.

Saunders gives us the character of Ray Abnesti, a scientist developing pharmaceuticals and using convicted felons as guinea pigs as part of the justice system. The wider world has forgotten about those whose crimes deserve punishment, whose fate goes unknown and unlamented. Then there is the theme of compassion. Abnesti explores love vs. lust for his own amusement. The different drugs Jeff is given prove that both are illusionary and fleeting. Yet Saunders implies that the truth of love is compassion. Jeff’s final action shows us that he is a man of compassion.

Then there is the theme of compassion. Abnesti explores love vs. lust for his own amusement. The different drugs Jeff is given prove that both are illusionary and fleeting. Yet Saunders implies that the truth of love is compassion. Jeff’s final action shows us that he is a man of compassion. A common theme in science fiction is the use of drugs to alter people’s behavior and control them emotionally. That theme is explored in detail here, ostensibly as a means to do away with prisons and reform prisoners. But really, these experiments are for Abnesti, a psychopath, to exercise his passion for the perverse and inhumane and for him to have power over the helpless.

A common theme in science fiction is the use of drugs to alter people’s behavior and control them emotionally. That theme is explored in detail here, ostensibly as a means to do away with prisons and reform prisoners. But really, these experiments are for Abnesti, a psychopath, to exercise his passion for the perverse and inhumane and for him to have power over the helpless. This short story was as powerful as any novel I’ve ever read, proving that a good story stays with the reader long after the final words have been read, no matter the length. His questions resonate, asking us to think about our true motives.

This short story was as powerful as any novel I’ve ever read, proving that a good story stays with the reader long after the final words have been read, no matter the length. His questions resonate, asking us to think about our true motives. Fortunately, Irene is editing the final draft of a book I finished during lockdown. She sends me one or two chapters with notes for final revisions each evening. That makes me happy—it’s been a while since I published a book.

Fortunately, Irene is editing the final draft of a book I finished during lockdown. She sends me one or two chapters with notes for final revisions each evening. That makes me happy—it’s been a while since I published a book. Sometimes we can visualize a complex theme but can’t explain it. If we can’t explain it, how do we show it? For me, that is the real struggle. Grief is a common theme that can play out against any backdrop, sci-fi or reality-based, where humans interact emotionally. But it is a complex theme, and people all react differently to it.

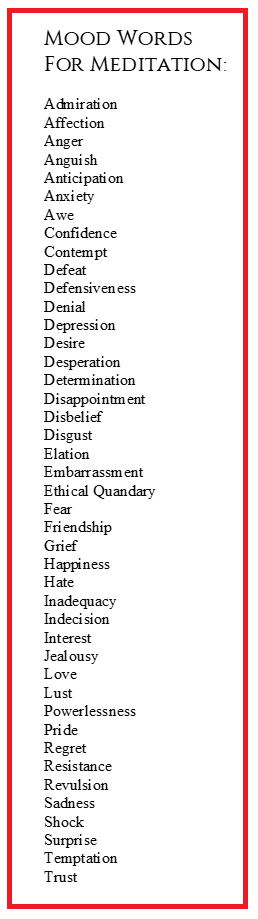

Sometimes we can visualize a complex theme but can’t explain it. If we can’t explain it, how do we show it? For me, that is the real struggle. Grief is a common theme that can play out against any backdrop, sci-fi or reality-based, where humans interact emotionally. But it is a complex theme, and people all react differently to it. Highlighting a strong theme is challenging, even when I begin with a plan. But once I have identified these personal themes, I’ll be able to write their stories. I’ll use actions, symbolic settings/places,

Highlighting a strong theme is challenging, even when I begin with a plan. But once I have identified these personal themes, I’ll be able to write their stories. I’ll use actions, symbolic settings/places,  Poets understand how central a theme is to the story. A poet takes the theme and builds the words around it. Emily Dickinson’s poems featured the themes of spirituality, love of nature, and death, which is why she appealed so strongly to me during my angsty young-adult life.

Poets understand how central a theme is to the story. A poet takes the theme and builds the words around it. Emily Dickinson’s poems featured the themes of spirituality, love of nature, and death, which is why she appealed so strongly to me during my angsty young-adult life. But that would be wrong. Poets write words that range far more widely than their physical surroundings. Some poets are constrained by unrewarding jobs, others may be “on the spectrum,” as they now say, and still others are constrained by physical limitations.

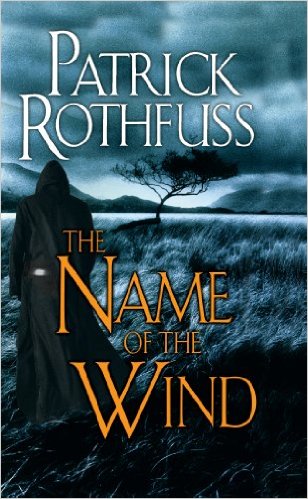

But that would be wrong. Poets write words that range far more widely than their physical surroundings. Some poets are constrained by unrewarding jobs, others may be “on the spectrum,” as they now say, and still others are constrained by physical limitations. Fantasy author

Fantasy author  Pride is a powerful theme because it is the downfall of many characters in all literature, not just Jane Austen’s work.

Pride is a powerful theme because it is the downfall of many characters in all literature, not just Jane Austen’s work.

Clearly, Mrs. Dashwood feels that ensuring her sisters-in-law are not impoverished would make her only son less rich. Less appealing to other affluent families.

Clearly, Mrs. Dashwood feels that ensuring her sisters-in-law are not impoverished would make her only son less rich. Less appealing to other affluent families. Henry James is famous for his novels and short stories laying bare the deepest motives and manipulations of the society he knew. However, he wrote one of the most famous novellas ever published,

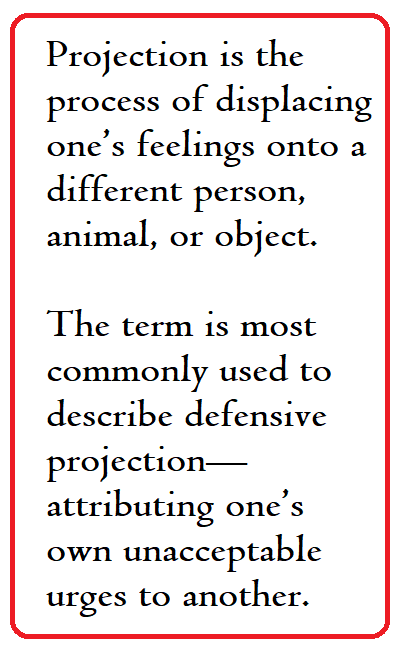

Henry James is famous for his novels and short stories laying bare the deepest motives and manipulations of the society he knew. However, he wrote one of the most famous novellas ever published, Projection

Projection Daily writing becomes easier once you make it a

Daily writing becomes easier once you make it a

A prompt is a word or visual image that kick starts the story in your head. If you need an idea, go to

A prompt is a word or visual image that kick starts the story in your head. If you need an idea, go to  When you write to a strict word count limit, every word is precious and must be used to the greatest effect. By shaving away the unneeded info in the short story, the author has more room to expand on the story’s theme and how it supports the plot.

When you write to a strict word count limit, every word is precious and must be used to the greatest effect. By shaving away the unneeded info in the short story, the author has more room to expand on the story’s theme and how it supports the plot.