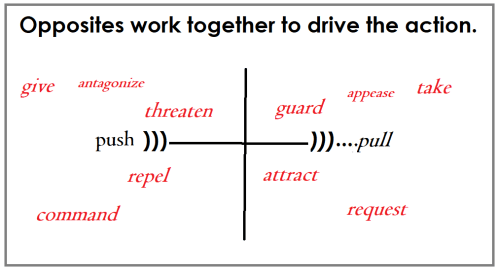

Verbs are the engine words of our prose. They show the action, but like all words, they have shades of mood, nuances that color the tone of my paragraphs. Verbs can either push the action outward from their partner nouns or pull it in.

When I write poetry, I look for words that contrast vividly against each other. I choose action words that begin with hard consonants, emotion words that begin with softer sounds.

When I write poetry, I look for words that contrast vividly against each other. I choose action words that begin with hard consonants, emotion words that begin with softer sounds.

If I can do this for poetry, I should be able to do this for narrative prose – but alas. For some reason, my poetic brain goes on vacation when I am trying to write a first draft. My work is filled with a bald telling of events.

But that’s okay. All I need at that point is to get the story written down.

But during revisions, when writing really becomes work, and I’m trying to turn that boring mess into something worth reading – that is when I need to use my words. Finding strong verbs and employing contrasts in my word choices becomes essential when embarking on the second draft.

I know that power verbs push action outward from a character. Other word choices pull the action inward, and contrasting the two creates a feeling of opposition and friction. This contrast of opposites injects dynamism into a passage, a sense of vitality, vigor, and energy.

Readers are attracted to dynamic prose.

Note to self: write dynamic prose.

Verbs that push the action outward from a character make them appear authoritative, competent, energetic, and decisive.

Verbs that pull the action in toward the character make them appear receptive, attentive, private, and flexible.

I want to make my characters well-rounded but not quite perfect. I hope they are relatable and human. The way I show their world and their place in it must convey who they are.

Concise writing is difficult for me because I love descriptors. So, I have to make my action words set the mood. To do that, I must use contrasts.

Concise writing is difficult for me because I love descriptors. So, I have to make my action words set the mood. To do that, I must use contrasts.

- Brood

- Deny

- Embrace

- Escape

- Consent

- Refuse

- Agony

- Ecstasy

A part of my life was burned away. I was destroyed, but now I was reborn in ways I’d never foreseen.

My action words are burn, destroy, and birth. This character’s entire arc is encapsulated in those three words. The contrasting words I choose throughout their story will make or break that novel.

Can I do it? I don’t know, but I’ll have fun trying. In the beginning, this character’s verbs will be darker, their actions more inward and brooding.

At the end of the story, events and interactions will alter them despite their desire to remain safely static. They will experience a renaissance, a flowering of the spirit.

But verbs and nouns by themselves don’t make engaging prose. They need modifiers and connectors.

I will have to select modifiers and connecting verbs to enhance contrasts. Since I can’t go wild with them, the few I choose must be power words.

Many power words begin with hard consonants. The images they convey project a feeling of power:

- Backlash

- Beating

- Beware

- Blinded

- Blood

- Bloodbath

- Bloodcurdling

- Bloody

- Blunder

When things get tricky and the characters are working their way through a problem, verbs like stumble and blunder offer a sense of chaos and don’t require a lot of modifiers to show the atmosphere. When you incorporate any of the above “B” words into your prose, you are posting a road sign for the reader, a notice that ahead lies danger.

Here are some words to create an atmosphere of anxiety – words that push the action outward:

- Agony (noun)

- Apocalypse (noun)

- Armageddon (noun)

- Assault (verb)

- Backlash (noun)

- Pale (modifier)

- Panic (verb or noun)

- Target (verb)

- Teeter (verb)

- Terrorize (verb)

Here are some words that draw us in:

- Delirious (intransitive verb)

- Depraved (modifier)

- Desire (verb)

- Dirty (modifier)

- Divine (modifier)

- Ecstatic (intransitive verb)

- Embrace (verb)

- Enchant (verb)

- Engage (verb)

- Entice (verb)

- Enthrall (verb)

Writing is an adventure, and I learn something new every day. Some days I like what I write; other days, not so much.

The drive to understand why some books enthrall me and others leave me cold keeps me reading and looking for new stories.

The drive to understand why some books enthrall me and others leave me cold keeps me reading and looking for new stories.

Life can be a bumpy road.

The key is to focus on the good things and laugh at the inconveniences. Make a little time to do something creative, and always make time for the people you love.

Unfortunately, although we asked for a ground-floor condo, we were assigned a second-floor unit. My husband is managing the stairs – slowly. On the good side, we have the god’s-eye view of a wide stretch of beach, the perfect deck overlooking it all.

Unfortunately, although we asked for a ground-floor condo, we were assigned a second-floor unit. My husband is managing the stairs – slowly. On the good side, we have the god’s-eye view of a wide stretch of beach, the perfect deck overlooking it all. Writing is going as well as ever, a little up and down. I’m building the framework for a new story, which I will begin writing on November 1st. The world is already built; it’s an established world with many things that are canon and can’t be changed. So, I’m working my way through the bag of tricks that help me jar things loose.

Writing is going as well as ever, a little up and down. I’m building the framework for a new story, which I will begin writing on November 1st. The world is already built; it’s an established world with many things that are canon and can’t be changed. So, I’m working my way through the bag of tricks that help me jar things loose. Protagonist HER: Anna Lundquist, an unemployed game developer. She inherited an old farm and has moved there. She embarks on creating her own business designing anime-based computer games. Anna is shy, not good with men unless discussing books or computer games. VOID: Loss of family. VERBS: Create, Build, Seek, Defend, Fight, Nurture. Modifiers: Adaptable, ambitious, focused, independent, industrious, mature, nurturing, private, resourceful, responsible, simple, thrifty.

Protagonist HER: Anna Lundquist, an unemployed game developer. She inherited an old farm and has moved there. She embarks on creating her own business designing anime-based computer games. Anna is shy, not good with men unless discussing books or computer games. VOID: Loss of family. VERBS: Create, Build, Seek, Defend, Fight, Nurture. Modifiers: Adaptable, ambitious, focused, independent, industrious, mature, nurturing, private, resourceful, responsible, simple, thrifty. Antagonist HIM: Matt Gentry, owner of MGPopularGames and Anna’s former boss, is angry at Anna for leaving his firm. On a skiing trip with an old fraternity brother who owns an art supply store in Starfall Ridge, he sees her entering Nic’s coffeeshop. Matt discovers that Anna is now living in that town. He learns she has started her own company and is building an anime-based RPG. He goes back to Seattle and files an injunction to stop her, claiming that he owns the rights to her intellectual property. VOID: Narcissist. VERBS: Possess, Control, Desire, Covet, Steal, Lie, Torment.

Antagonist HIM: Matt Gentry, owner of MGPopularGames and Anna’s former boss, is angry at Anna for leaving his firm. On a skiing trip with an old fraternity brother who owns an art supply store in Starfall Ridge, he sees her entering Nic’s coffeeshop. Matt discovers that Anna is now living in that town. He learns she has started her own company and is building an anime-based RPG. He goes back to Seattle and files an injunction to stop her, claiming that he owns the rights to her intellectual property. VOID: Narcissist. VERBS: Possess, Control, Desire, Covet, Steal, Lie, Torment.

We who write because we love words spend a great deal of time framing what our words say. We choose some words above others because they say what we mean more precisely, or they color our prose with the right emotion.

We who write because we love words spend a great deal of time framing what our words say. We choose some words above others because they say what we mean more precisely, or they color our prose with the right emotion. Two: Placement of verbs in the sentence can strengthen or weaken it.

Two: Placement of verbs in the sentence can strengthen or weaken it. Four: Contrast—In literature, we use contrast to describe the difference(s) between two or more things in one sentence. The blue sun burned like fire, but the ever-present wind chilled me.

Four: Contrast—In literature, we use contrast to describe the difference(s) between two or more things in one sentence. The blue sun burned like fire, but the ever-present wind chilled me. Seven: Alliteration is the occurrence of the same letter (or sound) at the beginning of successive words, such as the familiar tongue-twister: Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. Alliteration lends a poetic feeling to passages and enhances the atmosphere of a given scene without creating wordiness.

Seven: Alliteration is the occurrence of the same letter (or sound) at the beginning of successive words, such as the familiar tongue-twister: Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. Alliteration lends a poetic feeling to passages and enhances the atmosphere of a given scene without creating wordiness. Active phrasing generates emotion. Sometimes, using similes, repetition, and alliteration in subtle applications enhances the worldbuilding without beating your reader over the head.

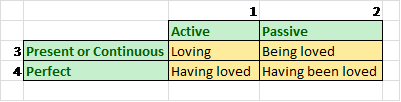

Active phrasing generates emotion. Sometimes, using similes, repetition, and alliteration in subtle applications enhances the worldbuilding without beating your reader over the head. In the written narrative, the many forms of this verb are what

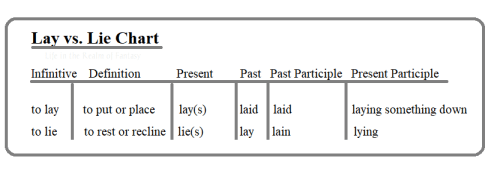

In the written narrative, the many forms of this verb are what  “Lay” is a transitive verb that refers to putting something in a horizontal position. At the same time, “lie” is an intransitive verb that refers to being in a flat position.

“Lay” is a transitive verb that refers to putting something in a horizontal position. At the same time, “lie” is an intransitive verb that refers to being in a flat position. To lie is an intransitive verb: it shows action, and the subject of the sentence engages in that action, but nothing is being acted upon (the verb has no direct object).

To lie is an intransitive verb: it shows action, and the subject of the sentence engages in that action, but nothing is being acted upon (the verb has no direct object).

The verb that means “to recline” is “to lie,” not “to lay.” If we are talking about the act of reclining, we use “lie,” not “lay.” “When I have a headache, I lie down.”

The verb that means “to recline” is “to lie,” not “to lay.” If we are talking about the act of reclining, we use “lie,” not “lay.” “When I have a headache, I lie down.”