Writers often find the words and rules we use to describe existence convoluted and hard to understand.

The subjunctive (in the English language) is used to form sentences that do not describe known objective facts.

In other words, subjunctives describe unknown intangible possibilities.

In other words, subjunctives describe unknown intangible possibilities.

William Shakespeare said it best in his tragedy, Hamlet: “To be or not to be… that is the question.”

Should he exist, or should he not exist—for the deeply depressed Dane, suicide or not suicide is the question. In his soliloquy, Hamlet contemplates death and suicide. He regrets the pain and unfairness of life but ultimately acknowledges that the alternative might be worse.

Be–a simple word, a verb that is a subjunctive. But sometimes the many forms of this word are overused in the narrative. The whole subjunctive thing looks quite complicated on the surface, but it doesn’t have to be. As writers of genre fiction, we have to identify the habitual overuse of subjunctives in our writing.

We must make our prose stronger by not using them except where nothing else will do. Most of the time, dialogue is the place for subjunctives, as in Hamlet’s monologue.

In writing fiction, subjunctives work well when used in conversations but create a passive voice when used in the narrative. They separate us from the story, remove the sense of immediacy that we as readers hope to experience.

But first, what does “subjunctive” mean?

http://www.Dictionary.com defines “Subjunctive” as:

adjective

-

(in English and certain other languages) noting or pertaining to a mood or mode of the verb that may be used for subjective, doubtful, hypothetical, or grammatically subordinate statements or questions, as the mood of ‘be’ in ‘if this be treason.’

-

the subjunctive mood or mode.

-

a verb in the subjunctive mood or form.

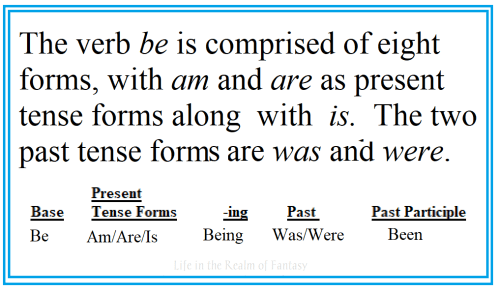

First, let’s consider existence and what Past Subjunctive Tense covers: how to use the words ‘was’ and ‘were,’ which are forms of the verb ‘be.’

English Club says: The English subjunctive is a special, relatively rare verb form that expresses something desired or imagined.

We use the subjunctive mainly when talking about events that are not certain to happen. For example, we use the subjunctive when talking about events that somebody:

-

wants to happen

-

anticipates will happen

-

imagines happening [1]

- I wish I were a penguin. I would fly through the water.

- I wish I was a penguin. I would fly through the water.

If I am only wishing that I were a penguin, were is correct.

However, if I could actually be a penguin, was would be correct, and I would have to rewrite my sentence by changing ‘would’ to ‘could.’

The Grammar Girl gives us a great example: Think of the song “If I Were a Rich Man,” from Fiddler on the Roof. When Tevye sings “If I were a rich man,” he is fantasizing about all the things he would do if he were rich. He’s not rich, he’s just imagining, so “If I were” is the correct statement. This time you’ve got a different clue at the beginning of the line: the word “if.” [2]

There are times when we use a form of the verb ‘was’ even though the subject of the sentence has not yet happened or may not happen at all: the past subjunctive verb form. It is unreal and may remain that way. “If I were.”

When you suppose about something that might be true, you use a form of the verb “was” and don’t sweat it.

If it’s likely real: Was (possibly is): I heard he was training his dog to fetch.

If it’s likely unreal: Were (possibly isn’t): If I were a penguin, I wouldn’t need to rent a tuxedo.

The past subjunctive verb forms express a hypothetical condition that may exist in a present, past, or future time:

- What if I was…

- I wish I were…

- If this be treason…

- To be or not to be…

Perhaps you are writing a technical manual, a dissertation, or an email to a client or coworker.

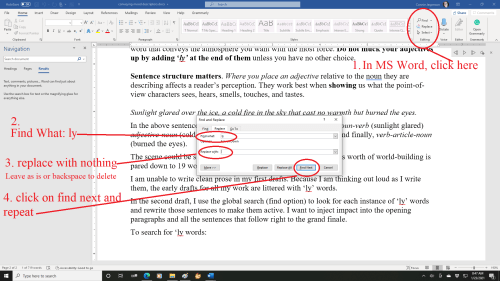

Despite the misguided efforts of many critique groups and Microsoft Word to erase all forms of ‘to be’ from the English language and replace it with ‘is,’ there are times when only a subjunctive will do the job.

When your intent is formal, subjunctives may abound, often in the form of commonly used phrases:

- Be that as it may.

- So be it.

- Suffice it to say.

- Come what may.

Steven Pinker is a Harvard professor whose discussions on the connections between language and what we see as humanity are eye-opening. He writes at a college level, but in his book, The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century, he raises a point that is important to this blogpost:

Subjunctives are hard to spot. Forms of “to be” can be found in subordinate clauses where something is mandated or required:

- I demand the prisoner be fed the same as anyone else.

A verb like “see” also has a subjunctive form when something is mandated or required:

- It’s essential that I see your report before you send it.

In ordinary writing, we rarely need to use subjunctives in clauses with mandates except perhaps in conversation.

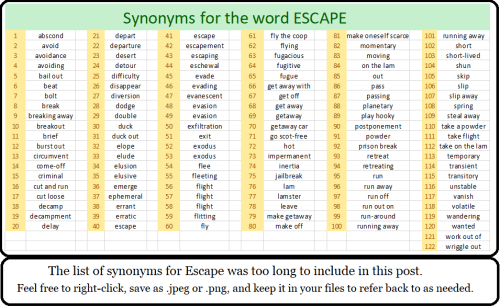

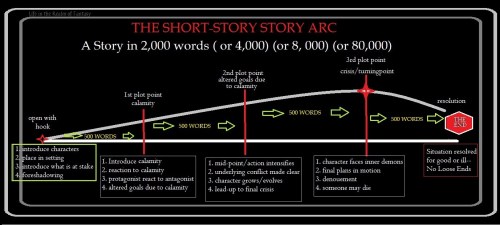

Feel free to copy and save the above graphic for your personal use: right click>copy>save as: .jpeg or.png.

We often “think aloud” in writing the first draft. We insert many passive phrasings into the raw narrative, words that I think of as traffic signals. These words are a shorthand that helped us get the story down, a guide that now shows us how we intend the story to go.

Subjunctives are small verbs of existence, but just like adverbs, they are telling words. In the rewrite, we look for these telling words, places where they have crept out of conversations and into the narrative.

We look at each instance and rewrite the paragraph to show the event, rather than tell about it.

- They were hot and thirsty could be shown as: They trudged on with dry, cracked lips, yearning for a drop of water.

That’s not a perfect example, but hopefully, you can see what I am trying to say.

Credits and Attributions:

EnglishClub contributors, Subjunctives © 1997-2021 EnglishClub.com All Rights Reserved https://www.englishclub.com/grammar/subjunctive.htm [1]

Subjunctive Verbs, by Mignon Fogarty, http://www.quickanddirtytips.com/education/grammar/subjunctive-verbs, Copyright © 2021 Macmillan Holdings, LLC. Quick & Dirty Tips™ [2]

“File:Penguin Front.png.” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 12 Sep 2020, 08:35 UTC. 6 Feb 2021, 17:14 <https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Penguin_Front.png&oldid=456325700>.