We’re well into NaNoWriMo, and writing is going well so far. I’m on track, and the words are flowing well. At our Saturday write-in, one of my fellow writers asked me how I introduce food into a narrative. As you might imagine, I have an opinion about that: I see food as set dressing, a part of world-building.

Food scenes serve as transitions between events. The act of dining occurs, but the conversations are the point of that scene. This is an opportunity to rest and regroup.

Food scenes serve as transitions between events. The act of dining occurs, but the conversations are the point of that scene. This is an opportunity to rest and regroup.

I write books set in fantasy environments, but you create a world no matter what genre you write in. As that world grows on paper, so does the culture. An aspect of worldbuilding involves including the casual mention of appropriate food for your ecology and level of technology.

I feel it’s best to concentrate on the conversations when writing about meals. The food should be part of the scenery. The conversations around food are where new information can be exchanged, things we need to know to move the story forward.

I’ve read many unforgettable fantasy books. One that shall go unnamed stands out, but not for a good reason. The author gave each kind of fruit, bird, or herd beast a different, usually unpronounceable, name in the language of her fantasy culture. She must have spent hours devising that hot mess of fantasy foods.

I’ve read many unforgettable fantasy books. One that shall go unnamed stands out, but not for a good reason. The author gave each kind of fruit, bird, or herd beast a different, usually unpronounceable, name in the language of her fantasy culture. She must have spent hours devising that hot mess of fantasy foods.

The characters were great and engaging, and the plot was engrossing. But the information about each and every kind of plant or vegetable was inserted into the narrative in long info dumps that ruined what could have been a great book for me.

As a reader, I think Tolkien got the food right when he created the Hobbit and the world of Middle Earth. He served common everyday food that his target audience was familiar with.

Food is an essential component of a culture but should be only briefly mentioned. Whether commonplace or exotic, it should be similar enough to known earthly foods to create an atmosphere a reader can easily visualize.

As many of you know, I have been vegan since 2012. However, during the 1980s, my second ex-husband and I raised sheep as part of a family cooperative.

I could write a book about those five years, but no one would believe it—fantasy is easier to make sense of.

I grew up fishing with my father and have a first-person understanding of putting meat, fish, or fowl on the table when a supermarket is not an option.

That experience taught me many things. Meat, fish, and fowl won’t be served daily in the average person’s home if they must catch, kill, and prepare it for themselves.

Village Scene with Well, Josse de Momper and Jan Brueghel II PD|100 via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s a lot of work to raise an animal. Hunting is also labor intensive. Then you have a lot of messy, smelly work to prepare it for cooking.

Travelers often streamline this process by skinning game birds rather than plucking them. The feathers come off with the skin – the whole point of hunting for dinner is to get it roasting as quickly as possible.

Why not raise animals and eat them? In the Middle Ages, pigs were raised solely for meat. The wool a sheep could produce in its lifetime was of far more value than the meat you might get by slaughtering it. For that reason, lamb was rarely served. The only sheep that made it to the table were usually rams culled from the herd.

Chickens were no different because you lose the many meals her eggs would have provided once a chicken is dead. Young roosters were culled before they got to the contentious stage and were usually the featured meat in the Sunday stew. Only one rooster was kept for breeding purposes. If he was too ill-tempered, he went into the stew pot, and a young rooster with better manners took his place.

Cattle and goats were also more valuable alive. Cows were integral to a family’s wealth as they were milk producers and sometimes worked as draft animals. Only one bull would be kept intact in a small herd for breeding purposes. The others would be neutered, made into oxen and draft animals that pulled plows, pulled wagons, fertilized the fields with their manure, and did all the work that heavy farm machinery does today.

In medieval times, it was a felony for commoners in Britain to hunt for game on many estates. Poachers were considered thieves and faced harsh penalties, horrific by our standards, if they were caught.

Cucumbers waiting to be pickles © 2013 cjjasp

However, most people were allowed to fish as long as they didn’t take salmon, so hutch-raised rabbits, fish, or salted pork were on the menu more often than fowl, sheep, or cattle. Eels and frogs were abundant and were a menu staple in the average peasant’s home. Anything one could raise in a garden was carefully harvested and pickled or dried. Berries were dried or made into jams and wines, as were tree fruits. Fish were dried and smoked or salted, and even pickled. These preserves were critical to surviving winters.

Common vegetables in medieval European gardens were leeks, garlic, onions, turnips, rutabagas, cabbages, carrots, peas, beans, cauliflower, squashes, gourds, melons, parsnips, aubergines (eggplants)—the list goes on and on. But what about fruits?

Wikipedia says:

Fruit was popular and could be served fresh, dried, or preserved, and was a common ingredient in many cooked dishes. Since sugar and honey were both expensive, it was common to include many types of fruit in recipes that called for sweeteners of some sort. The fruits of choice in the south were lemons, citrons, bitter oranges (the sweet type was not introduced until several hundred years later), pomegranates, quinces, and grapes. Farther north, apples, pears, plums, and wild strawberries were more common. Figs and dates were eaten all over Europe but remained expensive imports in the north. [1]

Pies of all kinds were the fast food of the era, often sold by vendors on the street or in bakeries.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder – Peasant Wedding (1526/1530–1569) via Wikimedia Commons

Wheat was rare and expensive. For that reason, the grains most often found in a European peasant’s home were barley, oats, and most importantly, rye. In the Americas, maize (corn)was the staple grain that provided flour for bread and was an essential ingredient in cooking.

Mostly, my characters eat fish, vegetables, grains, fruits, and nuts. The primary sources of protein are eggs, cheese, and fish. Herbal teas, ale, ciders, and mead are staples of the commoner’s diet. This is because drinking fresh, unboiled water can be unhealthy if your tale is set in a low-tech world. Medieval beers and ales were lower in alcohol but higher in nutrition than today’s brews. Ale or lager might be served at every meal, even to children.

In my current work in progress, my people have a melding of familiar European and New World ingredients for their diet and do a lot of foraging. Fish, maize, and potatoes are essential staples, as are beans and wild greens. For a good list of what this diet might entail, visit this link: Indigenous cuisine of the Americas. You will be amazed at the variety of everyday foods that originated in the Americas.

In my current work in progress, my people have a melding of familiar European and New World ingredients for their diet and do a lot of foraging. Fish, maize, and potatoes are essential staples, as are beans and wild greens. For a good list of what this diet might entail, visit this link: Indigenous cuisine of the Americas. You will be amazed at the variety of everyday foods that originated in the Americas.

Knowing what to feed your people keeps you from introducing jarring components into your narrative. But don’t make it the center of the scene unless your plot demands it. One of my favorite series does just that: Recipes for Love and Murder: A Tannie Maria Mystery (Tannie Maria Mystery, 1)

CREDITS AND ATTRIBUTIONS:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Medieval cuisine,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Medieval_cuisine&oldid=896980025 (accessed Nov 4, 2023).

Apples and pickles courtesy of the author’s own kitchen garden.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder – Peasant Wedding (1526/1530–1569) PD|100 via Wikimedia Commons.

Village Scene with Well, Josse de Momper and Jan Brueghel II PD|100 via Wikimedia Commons.

Also, my first drafts are not written linearly. I write what I am inspired to, skipping the spots I have no clue about. I fill in those places later. Even after completing the first draft, things will change structurally with each rewrite.

Also, my first drafts are not written linearly. I write what I am inspired to, skipping the spots I have no clue about. I fill in those places later. Even after completing the first draft, things will change structurally with each rewrite.

It wasn’t exactly literary brilliance, but it gave my idea a jumping-off point. I just began telling the story as it fell out of my mind. Surprisingly, I discovered my word count averaged 2,500 to 3,000 words daily. By day fifteen, I knew I would have no trouble getting to 50,000, and by November 21st, I had passed the 50,000-word mark.

It wasn’t exactly literary brilliance, but it gave my idea a jumping-off point. I just began telling the story as it fell out of my mind. Surprisingly, I discovered my word count averaged 2,500 to 3,000 words daily. By day fifteen, I knew I would have no trouble getting to 50,000, and by November 21st, I had passed the 50,000-word mark. But I took that incoherent mess apart, and over the next ten years, it became three books:

But I took that incoherent mess apart, and over the next ten years, it became three books:  It helps to check in on the national threads each day. Look at your regional threads on the national website to keep in contact with other local writers. You will find out when and where write-ins are scheduled.

It helps to check in on the national threads each day. Look at your regional threads on the national website to keep in contact with other local writers. You will find out when and where write-ins are scheduled. Included in this mess were ten dreadful poems, along with chapters 7 through 11 of

Included in this mess were ten dreadful poems, along with chapters 7 through 11 of  Conferences are excellent places to make good connections with other writers. You meet people you can talk to about every aspect of the experience of writing as well as craft. No one’s eyes glaze over when you try to explain your main character’s inner demons and you find people with struggles similar to your own.

Conferences are excellent places to make good connections with other writers. You meet people you can talk to about every aspect of the experience of writing as well as craft. No one’s eyes glaze over when you try to explain your main character’s inner demons and you find people with struggles similar to your own.

Some new writers are completely fired up for their novels, obsessed. They go at it full tilt for a week or even two, and then, at the 20,000-word mark, they take a day off. Somehow, they never get back to it. These writers will continue to write off and on and may participate in NaNoWriMo again.

Some new writers are completely fired up for their novels, obsessed. They go at it full tilt for a week or even two, and then, at the 20,000-word mark, they take a day off. Somehow, they never get back to it. These writers will continue to write off and on and may participate in NaNoWriMo again. Cooking is my love language. I have many tips and ideas for getting word count and having a proper family feast. As a dedicated writer, I know how to plan for all aspects of life.

Cooking is my love language. I have many tips and ideas for getting word count and having a proper family feast. As a dedicated writer, I know how to plan for all aspects of life.

How to get inspiration? That translates to getting a story idea. I used to think up nifty situations and wondered how an average person would deal with it. That’s the good ol’ what-if set-up you find mostly used in sci-fi stories. The problem with focusing on the cool idea is that usually the characters who have to deal with it become rather cardboard. That’s fine when you’re a young writer or producing a first draft. Slap it down and keep going. You can come back later to beef up the character, add description details, and so on. Whatever the idea is, get it out of your head at any cost.

How to get inspiration? That translates to getting a story idea. I used to think up nifty situations and wondered how an average person would deal with it. That’s the good ol’ what-if set-up you find mostly used in sci-fi stories. The problem with focusing on the cool idea is that usually the characters who have to deal with it become rather cardboard. That’s fine when you’re a young writer or producing a first draft. Slap it down and keep going. You can come back later to beef up the character, add description details, and so on. Whatever the idea is, get it out of your head at any cost. What is serious writing? Even if it’s comedy, it’s the writing you take seriously. What you want readers to admire, no matter the genre. That is all well and good, but you will find that what you think is good isn’t always what readers think is good. Got nothing to do with what you’re writing or how well you write it, it’s just the way it is. So don’t take yourself too seriously; you can take your writing seriously, of course. The idea is that the writing will get better for readers each time you go through a manuscript and revise and edit it. How many times you go through it is your decision. It helps to get someone else’s eyes on it at some point, especially if you are new at writing. You can look at a map but until you get to your destination you can’t be sure that map is accurate and you’re going the right way. Sounds like another thing I learned.

What is serious writing? Even if it’s comedy, it’s the writing you take seriously. What you want readers to admire, no matter the genre. That is all well and good, but you will find that what you think is good isn’t always what readers think is good. Got nothing to do with what you’re writing or how well you write it, it’s just the way it is. So don’t take yourself too seriously; you can take your writing seriously, of course. The idea is that the writing will get better for readers each time you go through a manuscript and revise and edit it. How many times you go through it is your decision. It helps to get someone else’s eyes on it at some point, especially if you are new at writing. You can look at a map but until you get to your destination you can’t be sure that map is accurate and you’re going the right way. Sounds like another thing I learned. I started reading a long time ago. Started writing soon after, making up my own stories which I thought were better than the ones I read. I borrowed here and there – and in later writing had to tone it down so as not to sound like the sources I borrowed from (sci-fi authors, mostly). You develop your own style eventually if you write enough. So write a lot; you don’t have to show it to anyone. I like to try writing in different styles, too. I like trying to have characters speak in different ways, some slang, vernacular, accents, different levels of education, just for my own amusement – which is cruel, I’ll admit. But trying different things is good for a writer. Read different styles, too, and try to imitate them. Read the juicy parts aloud, let them get stuck in your head. Consider what is special about the style the author uses. Compare and contrast with other authors you read, and with your own writing. Most of all, read a lot in different genre and different writing styles. How much you absorb from that differs for everyone, but try it.

I started reading a long time ago. Started writing soon after, making up my own stories which I thought were better than the ones I read. I borrowed here and there – and in later writing had to tone it down so as not to sound like the sources I borrowed from (sci-fi authors, mostly). You develop your own style eventually if you write enough. So write a lot; you don’t have to show it to anyone. I like to try writing in different styles, too. I like trying to have characters speak in different ways, some slang, vernacular, accents, different levels of education, just for my own amusement – which is cruel, I’ll admit. But trying different things is good for a writer. Read different styles, too, and try to imitate them. Read the juicy parts aloud, let them get stuck in your head. Consider what is special about the style the author uses. Compare and contrast with other authors you read, and with your own writing. Most of all, read a lot in different genre and different writing styles. How much you absorb from that differs for everyone, but try it. Finally you have a complete story (or novel) from beginning to end and the plot is satisfying, characters compelling, dialog crisp, and so on. What next? Read and revise at least three times, but put it away at least a few days between each reading (a month is optimal; go get some coffee). Yes, I know you’re eager to get into it again but make yourself wait. Go to your slush file and work on that erotica. Now back to your masterpiece. Try to read it as a reader who’s never seen it before: what would the average reader think and feel in this scene or on that page? You’re no longer thinking of how to write the story so now you focus on how someone you don’t know might understand it. (Sure, go ahead and correct those pesky mistypes as you find them. No rule saying you have to do that in a separate pass.) I like to look at scenes in isolation: every scene should do something, even if it is “only” showing a character’s personality. I read dialog aloud (or, recently, have my computer read it to me); I catch a lot of mistakes and sloppy or weak sentences that way. Run spellchecker until it’s about to fall off the rails but understand it is not actually reading and still will miss errors. You must read your manuscript with your own eyes and ears more than twice. Look for pet-peeve errors (e.g., I type ‘form’ a lot when I mean ‘from’; obviously the spellchecker will not catch it because ‘form’ is correctly spelled, just the wrong word). I run a search for them. Most importantly, never ever hit “replace all”!

Finally you have a complete story (or novel) from beginning to end and the plot is satisfying, characters compelling, dialog crisp, and so on. What next? Read and revise at least three times, but put it away at least a few days between each reading (a month is optimal; go get some coffee). Yes, I know you’re eager to get into it again but make yourself wait. Go to your slush file and work on that erotica. Now back to your masterpiece. Try to read it as a reader who’s never seen it before: what would the average reader think and feel in this scene or on that page? You’re no longer thinking of how to write the story so now you focus on how someone you don’t know might understand it. (Sure, go ahead and correct those pesky mistypes as you find them. No rule saying you have to do that in a separate pass.) I like to look at scenes in isolation: every scene should do something, even if it is “only” showing a character’s personality. I read dialog aloud (or, recently, have my computer read it to me); I catch a lot of mistakes and sloppy or weak sentences that way. Run spellchecker until it’s about to fall off the rails but understand it is not actually reading and still will miss errors. You must read your manuscript with your own eyes and ears more than twice. Look for pet-peeve errors (e.g., I type ‘form’ a lot when I mean ‘from’; obviously the spellchecker will not catch it because ‘form’ is correctly spelled, just the wrong word). I run a search for them. Most importantly, never ever hit “replace all”! Stephen Swartz is the author of literary fiction, science fiction, fantasy, romance, and contemporary horror novels. While growing up in Kansas City, he dreamed of traveling the world. His novels feature exotic locations, foreign characters, and smatterings of other languages–strangers in strange lands. You get the idea: life imitating art.

Stephen Swartz is the author of literary fiction, science fiction, fantasy, romance, and contemporary horror novels. While growing up in Kansas City, he dreamed of traveling the world. His novels feature exotic locations, foreign characters, and smatterings of other languages–strangers in strange lands. You get the idea: life imitating art. By just doing that, I will have 50,000 (or more) words by midnight on November 30th.

By just doing that, I will have 50,000 (or more) words by midnight on November 30th. Be willing to be flexible. Do you work best in short bursts? Or, maybe you’re at your best when you have a long session of privacy and quiet time. Something in the middle, a melding of the two, works best for me.

Be willing to be flexible. Do you work best in short bursts? Or, maybe you’re at your best when you have a long session of privacy and quiet time. Something in the middle, a melding of the two, works best for me. A good way to ensure you have that time is to encourage your family members to indulge in their own interests and artistic endeavors. That way, everyone can be creative in their own way during that hour, and they will understand why you value your writing time so much.

A good way to ensure you have that time is to encourage your family members to indulge in their own interests and artistic endeavors. That way, everyone can be creative in their own way during that hour, and they will understand why you value your writing time so much. Writers and other artists do have to make some sacrifices for their craft. It’s just how things are. But don’t sacrifice your family for it.

Writers and other artists do have to make some sacrifices for their craft. It’s just how things are. But don’t sacrifice your family for it. But we all know infodumps are an insidious poison, so how do we apply this backstory without losing the reader?

But we all know infodumps are an insidious poison, so how do we apply this backstory without losing the reader? Character A is a shaman, a fire-mage smith and warrior, and is slated to be the next War Leader of the tribes. His shamanic purpose is to unite the people, both the tribes and those citadels who have turned tribeless. He is the chosen champion of the Goddess his sect of mages serves, and his success or failure will determine her fate.

Character A is a shaman, a fire-mage smith and warrior, and is slated to be the next War Leader of the tribes. His shamanic purpose is to unite the people, both the tribes and those citadels who have turned tribeless. He is the chosen champion of the Goddess his sect of mages serves, and his success or failure will determine her fate. This void is vital because characters must overcome fear to face it. As a reader, one characteristic I’ve noticed in my favorite characters is they each have a hint of self-deception. All the characters – the antagonists and the protagonists – deceive themselves in some way about their own motives.

This void is vital because characters must overcome fear to face it. As a reader, one characteristic I’ve noticed in my favorite characters is they each have a hint of self-deception. All the characters – the antagonists and the protagonists – deceive themselves in some way about their own motives.

In his book,

In his book,  The story follows a group of

The story follows a group of  However, when the antagonist is a person, I ask myself, why this person opposes the protagonist? What drives them to create the roadblocks they do? Why do they feel justified in doing so?

However, when the antagonist is a person, I ask myself, why this person opposes the protagonist? What drives them to create the roadblocks they do? Why do they feel justified in doing so? We must remember that the characters in our stories don’t go through their events and trials alone. We drag the reader along for the ride the moment we begin writing the story. They need to know why they’re in that handbasket and where the enemy thinks they’re going, or the narrative will make no sense.

We must remember that the characters in our stories don’t go through their events and trials alone. We drag the reader along for the ride the moment we begin writing the story. They need to know why they’re in that handbasket and where the enemy thinks they’re going, or the narrative will make no sense. I quickly regretted that decision.

I quickly regretted that decision. Arthur and his court originated as ordinary 5th or 6th-century warlords. But the tales featuring them were written centuries later. Their 11th-century chroniclers presented them in contemporary armor as worn by

Arthur and his court originated as ordinary 5th or 6th-century warlords. But the tales featuring them were written centuries later. Their 11th-century chroniclers presented them in contemporary armor as worn by

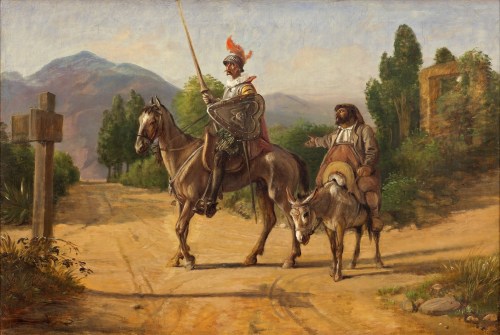

I am an abject fangirl for Don Quixote, so different versions of both Galahad and Quixote appear regularly in my work.

I am an abject fangirl for Don Quixote, so different versions of both Galahad and Quixote appear regularly in my work.

And sometimes a theme refuses to let go of me. I took Arthurian myth and the chivalric code and turned them inside out with the characters of Lancelyn and Galahad in

And sometimes a theme refuses to let go of me. I took Arthurian myth and the chivalric code and turned them inside out with the characters of Lancelyn and Galahad in  During the 1980s and 90s, I listened to music on the stereo, writing my thoughts and ideas in a notebook while my kids did their homework. I drew dragons and fantasy landscapes and worked three part-time jobs to pay the bills.

During the 1980s and 90s, I listened to music on the stereo, writing my thoughts and ideas in a notebook while my kids did their homework. I drew dragons and fantasy landscapes and worked three part-time jobs to pay the bills. For most of my writing life, I was like a toddler given a package of

For most of my writing life, I was like a toddler given a package of  Build a glossary of words and spellings unique to your story, and be sure to list names. I use an Excel spreadsheet, but you can use anything you like to help you stay consistent in your spelling.

Build a glossary of words and spellings unique to your story, and be sure to list names. I use an Excel spreadsheet, but you can use anything you like to help you stay consistent in your spelling. The master file might be titled: Lenns_Story

The master file might be titled: Lenns_Story I gained a fantastic local group through attending write-ins for NaNoWriMo, the Tuesday Morning Rebel Writers. Since the pandemic, and with several of our members now on the opposite side of Washington State, we meet weekly via Zoom. We are a group of authors writing in a wide variety of genres.

I gained a fantastic local group through attending write-ins for NaNoWriMo, the Tuesday Morning Rebel Writers. Since the pandemic, and with several of our members now on the opposite side of Washington State, we meet weekly via Zoom. We are a group of authors writing in a wide variety of genres. Learn about structure and pacing from successful authors. Spend the money to go to conventions and attend seminars. You will learn so much about the craft of writing, the genre you write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things you can only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining

Learn about structure and pacing from successful authors. Spend the money to go to conventions and attend seminars. You will learn so much about the craft of writing, the genre you write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things you can only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining  The year that followed was filled with mistakes and struggles. Legitimate publishers NEVER contact you. You must submit your work to them, and they prefer to work with agented authors.

The year that followed was filled with mistakes and struggles. Legitimate publishers NEVER contact you. You must submit your work to them, and they prefer to work with agented authors. Short stories and micro fiction are a training ground, a way to hone your skills. They’re also the best way to get your name out there. I suggest you build a backlog of work from 100 to 5,000 words in length. Keep them ready to submit to magazines, anthologies, and contests.

Short stories and micro fiction are a training ground, a way to hone your skills. They’re also the best way to get your name out there. I suggest you build a backlog of work from 100 to 5,000 words in length. Keep them ready to submit to magazines, anthologies, and contests. One of my favorite authors writes great storylines and creates wonderful characters. Unfortunately, the quality of his work has deteriorated over the last decade. It’s clear that he has succumbed to the pressure from his publisher, as he is putting out four or more books a year.

One of my favorite authors writes great storylines and creates wonderful characters. Unfortunately, the quality of his work has deteriorated over the last decade. It’s clear that he has succumbed to the pressure from his publisher, as he is putting out four or more books a year. This frequently happens to me in a first draft, but whoever is editing for him is letting it slide, as it pads the word count, making his books novel-length. I suspect they don’t have time to do any significant revisions.

This frequently happens to me in a first draft, but whoever is editing for him is letting it slide, as it pads the word count, making his books novel-length. I suspect they don’t have time to do any significant revisions. When we lay down the first draft, the story emerges from our imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard). Even with an outline, the story forms in our heads as we write it. While we think it is perfect as is, it probably isn’t.

When we lay down the first draft, the story emerges from our imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard). Even with an outline, the story forms in our heads as we write it. While we think it is perfect as is, it probably isn’t. Inadvertent repetition causes the story arc to dip. It takes us backward rather than forward. In my work, I have discovered that the second version of that idea is usually better than the first.

Inadvertent repetition causes the story arc to dip. It takes us backward rather than forward. In my work, I have discovered that the second version of that idea is usually better than the first. Here are a few things that stand out when I do this:

Here are a few things that stand out when I do this: