In all my favorite science fiction and fantasy novels, the enemy has access to equal or better science or magic. The story is about how the characters overcome the limitations of their science, magic, or superpower and succeed in their quest.

Magic should exist as an underlying, invisible layer of your written universe, the way gravity exists in reality. We know gravity works and accept it as a part of daily life.

Magic should exist as an underlying, invisible layer of your written universe, the way gravity exists in reality. We know gravity works and accept it as a part of daily life.

Magic should operate with the same limitations that, say, light photons have. Photons can do some things, and they cannot do others.

Your story won’t contradict itself if you establish the known physics of magic before you begin using and abusing it.

As a confirmed lover of all things fantasy, I read a great deal of both indie and traditionally published work. Both sides of the publishing industry are guilty of publishing novels that aren’t well thought out.

Inconsistencies in the magic system are usually only one aspect of a poorly planned world. It’s easy to tell when an author doesn’t consider the possible contradictions that might emerge as the story progresses.

When the magic is mushy, the rest of the setting reads as if they just wrote whatever came into their head and didn’t check for logic or do much revising.

If all the typos are edited out of the manuscript, and the characters are brilliant and engaging, the author might be able to carry it off. Unfortunately, mushy magic or science usually results in a book I can’t recommend.

We have several things to consider in designing a story where magic and superpowers are fundamental plot elements.

First, the ability to use magic is either learned through spells, an inherent gift, or both. Your world should establish which kind of path you are taking at the outset.

First, the ability to use magic is either learned through spells, an inherent gift, or both. Your world should establish which kind of path you are taking at the outset.

- Magic is not science as we know it but should be logical and rooted in solid theories.

As a reader, I can suspend my disbelief if magic is only possible when certain conditions have been met. The most believable magic occurs when the author creates a system that regulates what the characters can do.

Magic is believable if the number of people who can use it is restricted, how it can be used is limited, and most mages are constrained to one or two kinds of magic. It becomes more believable if only certain mages can use every type of magic.

Why restrict your beloved main character’s abilities? No one has all the skills in real life, no matter how good they are at their job.

Consider musicians. A person who wins international piano competitions most likely won’t be a virtuoso at brass instruments.

Consider musicians. A person who wins international piano competitions most likely won’t be a virtuoso at brass instruments.

This is because virtuosity requires hours of practice on one thing, working on the most minor details of technique and tone. That kind of intense focus doesn’t leave room for branching into other areas of music.

Magicians and wizards should develop skills and abilities the way musicians do. Virtuosity requires complete dedication and focus. Some are naturally talented but without practice they never rise to the top.

Magic becomes believable if the physics of magic define what each kind of magic can do.

Those rules should define the conditions under which magic works. The same physics should explain why it won’t work if those conditions are not met.

Are you writing a book that features magic? I have a few questions that you may want to consider:

Are there some conditions under which the magic will not work? Is the damage magic can do as a weapon, or is the healing it can perform somehow limited?

Does the mage or healer pay a physical/emotional price for using or abusing magic? Is the learning curve steep and sometimes lethal?

When you answer the above questions, you create the Science of Magic.

So, what about superpowers? Aren’t they magic?

Superpowers are both science and something that may seem like magic, but they are not. Think Spiderman. His abilities are conferred on him by a scientific experiment that goes wrong.

Like science and magic, superpowers are believable when they are limited in what they can do.

Like science and magic, superpowers are believable when they are limited in what they can do.

If you haven’t considered the challenges your characters must overcome when learning to wield their magic/superpower, now is a good time to do it.

- Are they unable to fully use their abilities?

- If so, why?

- How does their inability affect their companions?

- How is their self-confidence affected by this inability?

- Do the companions face learning curves too?

- What has to happen before your hero can fully realize their abilities?

These limits are the roadblocks to success, and overcoming those roadblocks is what the story is all about. The struggle forces the characters out of their comfortable environment.

The roadblocks you put up force them to be creative, and through that creativity, your characters become more than they believe they are. The reader becomes invested in the outcome of the story.

The next post in this series will delve into powers that are familiar tropes of fantasy: healing and telepathy.

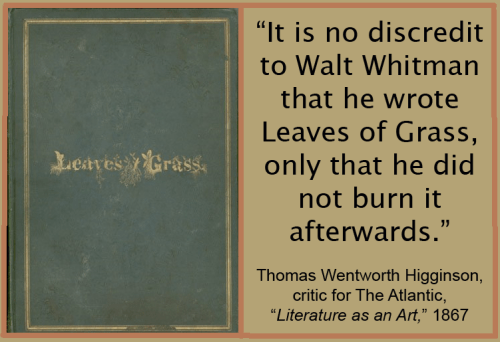

However, we can learn a great deal from books embodying poorly executed plots and badly scripted dialogue.

However, we can learn a great deal from books embodying poorly executed plots and badly scripted dialogue. Structurally, the books in this subseries feel like he knew how to end it but struggled to fill in the arc. Past events and conversations get repeated verbatim to every new character. Long passages of remembering and agonizing over what is done and dusted fluffs up the narrative.

Structurally, the books in this subseries feel like he knew how to end it but struggled to fill in the arc. Past events and conversations get repeated verbatim to every new character. Long passages of remembering and agonizing over what is done and dusted fluffs up the narrative. To me, book 21 reads as if (while books 19 and 20 were in the publishing gauntlet) he still had to fluff up the ending to make book 21 long enough to be considered a novel. The evidence of a lack of genuine inspiration is the absurd “scar” the protagonist is left with after winning an unbelievable victory and nearly dying.

To me, book 21 reads as if (while books 19 and 20 were in the publishing gauntlet) he still had to fluff up the ending to make book 21 long enough to be considered a novel. The evidence of a lack of genuine inspiration is the absurd “scar” the protagonist is left with after winning an unbelievable victory and nearly dying. Everyone, even your favorite author, writes a stinker now and then.

Everyone, even your favorite author, writes a stinker now and then.  It deals with things like the mass of objects, the speed at which they travel, how speed and mass are converted to energy, and how mass warps the fabric of space and time.

It deals with things like the mass of objects, the speed at which they travel, how speed and mass are converted to energy, and how mass warps the fabric of space and time. But what about “It?” Here, we are dealing with possession by the inanimate. We don’t need an exorcist, although a good maid service would resolve a great deal here at Casa del Jasperson. But in this case, we are referencing something owned by the inanimate:

But what about “It?” Here, we are dealing with possession by the inanimate. We don’t need an exorcist, although a good maid service would resolve a great deal here at Casa del Jasperson. But in this case, we are referencing something owned by the inanimate: In the case of number 4, the sentence would be stronger without it. Most of the time, the prose is made stronger when the word “that” is cut and not replaced with anything. I say most, but not all the time.

In the case of number 4, the sentence would be stronger without it. Most of the time, the prose is made stronger when the word “that” is cut and not replaced with anything. I say most, but not all the time.

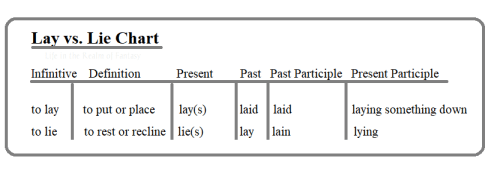

In the written narrative, the many forms of this verb are what

In the written narrative, the many forms of this verb are what  “Lay” is a transitive verb that refers to putting something in a horizontal position. At the same time, “lie” is an intransitive verb that refers to being in a flat position.

“Lay” is a transitive verb that refers to putting something in a horizontal position. At the same time, “lie” is an intransitive verb that refers to being in a flat position. To lie is an intransitive verb: it shows action, and the subject of the sentence engages in that action, but nothing is being acted upon (the verb has no direct object).

To lie is an intransitive verb: it shows action, and the subject of the sentence engages in that action, but nothing is being acted upon (the verb has no direct object).

The verb that means “to recline” is “to lie,” not “to lay.” If we are talking about the act of reclining, we use “lie,” not “lay.” “When I have a headache, I lie down.”

The verb that means “to recline” is “to lie,” not “to lay.” If we are talking about the act of reclining, we use “lie,” not “lay.” “When I have a headache, I lie down.” All around us, gravity works in hidden ways. Gravity on a small scale keeps everything securely stuck to the surface of Planet Earth.

All around us, gravity works in hidden ways. Gravity on a small scale keeps everything securely stuck to the surface of Planet Earth. Creating memorable characters is the goal of all authors. After all, who would read a book with bland and uninteresting dialogue? Dialogue is where most information is given to the characters and the reader. However, when we are just beginning to write, many of us are confused about how to punctuate conversations. It’s not that complicated. Here are four rules to remember:

Creating memorable characters is the goal of all authors. After all, who would read a book with bland and uninteresting dialogue? Dialogue is where most information is given to the characters and the reader. However, when we are just beginning to write, many of us are confused about how to punctuate conversations. It’s not that complicated. Here are four rules to remember: When you envision your characters in conversation, you must think about what the word natural means. People don’t only use their words to communicate. Bodies and faces tell us a great deal about a person’s mood and what they feel.

When you envision your characters in conversation, you must think about what the word natural means. People don’t only use their words to communicate. Bodies and faces tell us a great deal about a person’s mood and what they feel. For this reason, we don’t want to inject an excess of flushing, smirking, eye-rolling, or shrugging into the story. Those actions have a specific use in conveying the mood, but anything used too frequently becomes a crutch.

For this reason, we don’t want to inject an excess of flushing, smirking, eye-rolling, or shrugging into the story. Those actions have a specific use in conveying the mood, but anything used too frequently becomes a crutch. We are emotional creatures. When we are just starting on this path, getting an unbiased critique for something you think is the best thing you ever wrote can feel unfair.

We are emotional creatures. When we are just starting on this path, getting an unbiased critique for something you think is the best thing you ever wrote can feel unfair.

I could have embarrassed myself and responded childishly, but that would have been foolish and self-defeating. When I really thought about it, I realized that particular plot twist had been done many times before. I thanked him for his time because I had learned something valuable from that experience.

I could have embarrassed myself and responded childishly, but that would have been foolish and self-defeating. When I really thought about it, I realized that particular plot twist had been done many times before. I thanked him for his time because I had learned something valuable from that experience. Treat all your professional contacts with courtesy, no matter how angry you are. Allow yourself some time to cool off. Don’t have a tantrum and immediately respond with an angst-riddled rant.

Treat all your professional contacts with courtesy, no matter how angry you are. Allow yourself some time to cool off. Don’t have a tantrum and immediately respond with an angst-riddled rant. When you are pantsing it (writing-by-the-seat-of-your-pants), themes are like your drunk uncle. They hang out at the local pub until closing time and then weave their way home through dark alleys. Sometimes, as you are leaving for work in the morning, you find them under the neighbor’s shrubs. Other times they make it home.

When you are pantsing it (writing-by-the-seat-of-your-pants), themes are like your drunk uncle. They hang out at the local pub until closing time and then weave their way home through dark alleys. Sometimes, as you are leaving for work in the morning, you find them under the neighbor’s shrubs. Other times they make it home. I often sit on my back porch and just let my thoughts roam, thinking about nothing in particular. Usually, I will end up considering the character’s quest or dilemma. I ask myself what the root cause of the issue is—if it is a crime, why is crime rampant? Is it a societal problem, such as poverty or war? If the core dilemma is unrequited love, what are the roadblocks to a resolution?

I often sit on my back porch and just let my thoughts roam, thinking about nothing in particular. Usually, I will end up considering the character’s quest or dilemma. I ask myself what the root cause of the issue is—if it is a crime, why is crime rampant? Is it a societal problem, such as poverty or war? If the core dilemma is unrequited love, what are the roadblocks to a resolution? These layers offer us an incredible amount of subliminal information about that surreal world and what is going on in reality, what the Matrix truly is.

These layers offer us an incredible amount of subliminal information about that surreal world and what is going on in reality, what the Matrix truly is. Poets understand how central a theme is to the story. A poet takes the theme and builds the words around it. Emily Dickinson’s poems featured the themes of spirituality, love of nature, and death, which is why she appealed so strongly to me during my angsty young-adult life.

Poets understand how central a theme is to the story. A poet takes the theme and builds the words around it. Emily Dickinson’s poems featured the themes of spirituality, love of nature, and death, which is why she appealed so strongly to me during my angsty young-adult life. But that would be wrong. Poets write words that range far more widely than their physical surroundings. Some poets are constrained by unrewarding jobs, others may be “on the spectrum,” as they now say, and still others are constrained by physical limitations.

But that would be wrong. Poets write words that range far more widely than their physical surroundings. Some poets are constrained by unrewarding jobs, others may be “on the spectrum,” as they now say, and still others are constrained by physical limitations. Fantasy author

Fantasy author  Even today, her humor shines with sharp-edged wit delivered without condescension. Her most memorable protagonists rise above the trivialities of life that absorb the sillier characters.

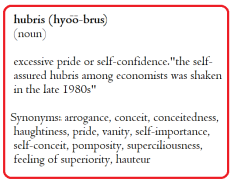

Even today, her humor shines with sharp-edged wit delivered without condescension. Her most memorable protagonists rise above the trivialities of life that absorb the sillier characters. Pride is a powerful theme because it is the downfall of many characters in all literature, not just Jane Austen’s work.

Pride is a powerful theme because it is the downfall of many characters in all literature, not just Jane Austen’s work.

Clearly, Mrs. Dashwood feels that ensuring her sisters-in-law are not impoverished would make her only son less rich. Less appealing to other affluent families.

Clearly, Mrs. Dashwood feels that ensuring her sisters-in-law are not impoverished would make her only son less rich. Less appealing to other affluent families. Many of James’s books feature one common theme—lust.

Many of James’s books feature one common theme—lust. Henry James is famous for his novels and short stories laying bare the deepest motives and manipulations of the society he knew. However, he wrote one of the most famous novellas ever published,

Henry James is famous for his novels and short stories laying bare the deepest motives and manipulations of the society he knew. However, he wrote one of the most famous novellas ever published, Projection

Projection