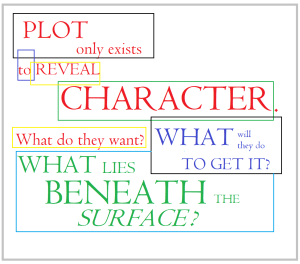

To create characters with emotional depth, you must swim with the sharks of show-and-tell. Most authors who have been in writing groups for any length of time become adept at writing emotions on a surface level.

We work to show our characters’ facial expressions, whether happiness, anger, or spite, etc. We show their eyebrows raise or draw together. Their foreheads crease and eyes twinkle; shoulders slump and hands tremble; lips turn up and dimples pop; lips curve down and eyes spark … and so on and so on.

We work to show our characters’ facial expressions, whether happiness, anger, or spite, etc. We show their eyebrows raise or draw together. Their foreheads crease and eyes twinkle; shoulders slump and hands tremble; lips turn up and dimples pop; lips curve down and eyes spark … and so on and so on.

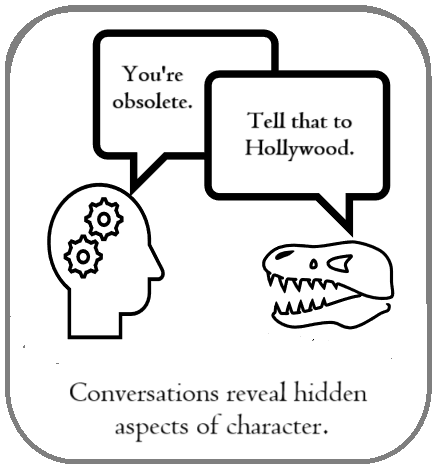

When done sparingly and combined with conversation, this can work. But no more than one facial change per interaction, please. Nothing is more off-putting than reading a story where each character’s facial expressions take center stage.

Writing emotions with depth is a balancing act. Expressions and body language can only hint at the internal thoughts and feelings of a character, as showing the outward physical indicators of a particular emotion is only half the story.

This is where we write from real life. When someone is happy, what do you see? Bright eyes, laughter, and smiles. When you are happy, how do you feel? Energized, confident.

How do we show it? Through the observations, both spoken and unspoken, of the main characters and those close to them.

How do we show it? Through the observations, both spoken and unspoken, of the main characters and those close to them.

In revisions, I look at each scene and try to combine the physical evidence of personal mood with the deeper aspect of the emotion. I combine spoken dialogue and internal dialogue with physical cues to offer hints as to why a character is feeling a certain way.

The hard part is to write it so I don’t tell the reader what to experience. I love it when an author makes the emotion feel as if it is the reader’s idea.

Here is a short list of simple, commonly used, easy to describe, surface emotions. These are easy to show through conversations and physical cues.

- Anger

- Anticipation

- Awe

- Confidence

- Contempt

- Defensiveness

- Denial

- Desire

- Desperation

- Determination

- Disappointment

- Disbelief

- Disgust

- Elation

- Embarrassment

- Fear

- Friendship

- Grief

- Happiness

- Hate

- Interest

- Love

- Pride

- Revulsion

- Sadness

- Shock

- Surprise

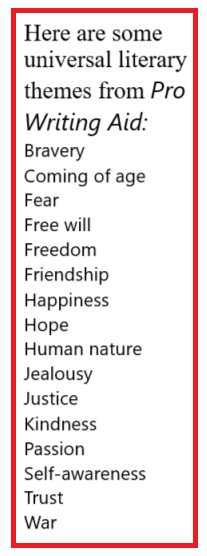

Other emotions are tricky because they are more difficult to show physically unless some background information is included. They are complicated and deeply personal, but these are the gut-wrenching emotions that make our work speak to the reader.

So, here is an even shorter list of complex emotions:

- Anguish

- Anxiety

- Defeat

- Depression

- Indecision

- Jealousy

- Ethical Quandary

- Inadequacy

- Lust

- Powerlessness

- Regret

- Resistance

- Temptation

- Trust

- Unease

- Weakness

When I began writing seriously in the 1990s, I had no idea how to convey the basic emotions of my characters other than through dialogue, a form of telling. Other writers have the opposite problem, and their characters smile, and smile, and grin, and smile. It is showing … but not showing very much other than a lack of inspiration on the writer’s part.

I had good mentors and editors in those days, and through their kind suggestions, I have learned ways to combine the showing and telling. The key is to think of them as salt and garlic powder: a little of each makes the soup delicious but too much ruins it.

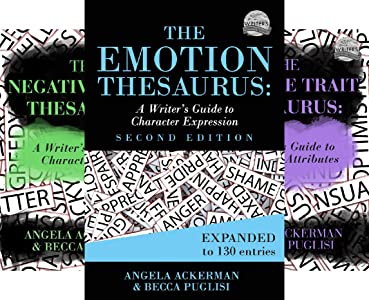

If you are just starting out, and don’t know how to include physical cues in a scene, a good handbook that offers a jumping off point is The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi. This book is affordable and full of hints that you can use to give depth to your characters, which makes the story deeper as a whole.

If you are just starting out, and don’t know how to include physical cues in a scene, a good handbook that offers a jumping off point is The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi. This book is affordable and full of hints that you can use to give depth to your characters, which makes the story deeper as a whole.

Just don’t go overboard. They will offer nine or ten hints that are physical indications for each of a wide range of surface emotions. Do your readers a favor and only choose one physical indicator per emotion, per scene.

I say this because it is easy to make a mockery of your characters, turning them into melodramatic cartoons.

I say this because it is easy to make a mockery of your characters, turning them into melodramatic cartoons.

- Subtle physical hints, along with some internal dialogue laced into the narrative show a rounded character, one who is not mentally unhinged.

Each of us experiences emotional highs and lows in our daily lives. We have deep-rooted, personal reasons for our emotions. Our characters must have credible reasons too, inspired by a flash of memory or a sensory prompt that a reader can empathize with.

Why does a blind alley or a vacant lot make a character nervous?

- Perhaps they were attacked and robbed in such a place.

Why does a grandmother hoard food?

- Perhaps her baby sister died of starvation.

Why does the sight of daisies make an old man smile?

- He might be remembering the best day of his life, sixty years before.

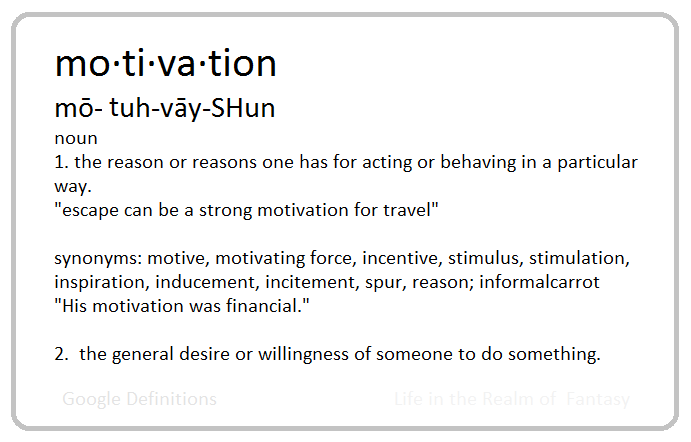

Writing genuine emotions requires practice and thought. I’ve mentioned this before, but motivation is key. WHY does the character react with that emotion? Emotions that are undermotivated have no base for existence, no foundation.

Writing genuine emotions requires practice and thought. I’ve mentioned this before, but motivation is key. WHY does the character react with that emotion? Emotions that are undermotivated have no base for existence, no foundation.

The story feels shallow, a lot of noise about nothing. Hints of backstory offered through dialogue, either internal or spoken, can resolve this.

Another thing to consider is timing. The moment to mention the character’s memory is when the physical response to the emotion hits and the character is processing it. That way, there is a reason for their sudden nausea. With small hints, you avoid the dreaded info dump, and the reader begins to see the needed backstory. They want to keep reading to discover the whole truth.

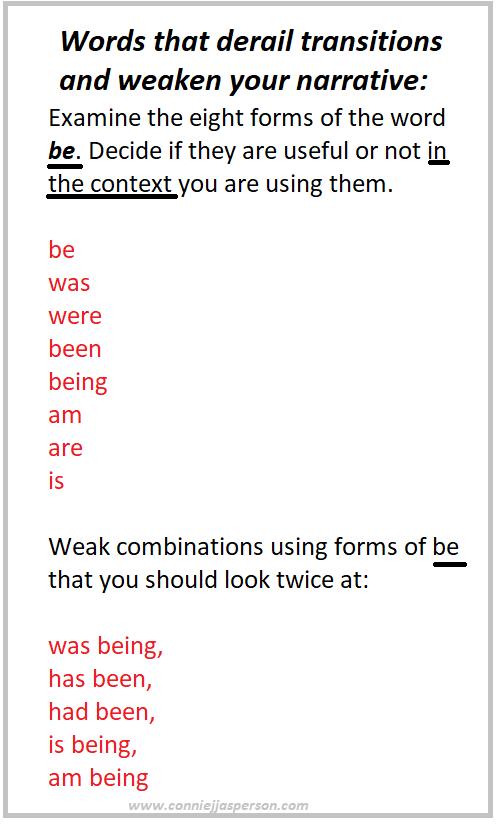

Phrasing and word choices can convey emotional impact in your narrative. If you use powerful words, you won’t have to resort to a great deal of description.

- I don’t worry about this in the first draft. The second draft is where I check for weak word choices.

Passive phrasings are first draft clues, places where I was just trying to get the story on paper. If they are left in the final draft, they separate the reader from the experience, negating the emotional impact of what could be a powerful scene.

Passive phrasings are first draft clues, places where I was just trying to get the story on paper. If they are left in the final draft, they separate the reader from the experience, negating the emotional impact of what could be a powerful scene.

The trick is to avoid writing maudlin caricatures of emotions, and over-the-top melodrama.

The books I love are written with bold, strong words and phrasing. The emotional lives of their characters are real and immediate to me. Those are the kind of characters that have depth and are memorable.

The books I love are written with bold, strong words and phrasing. The emotional lives of their characters are real and immediate to me. Those are the kind of characters that have depth and are memorable.

A good exercise for writing deep emotions is to create character sketches for characters you currently have no use for. I say this because just as in all the many other skills necessary to the craft of writing a balanced narrative, practice is required.

Practice really does make the imperfections in our writing less noticeable, and you may find a later use for these practice characters. They may be the seeds of a marketable short story.

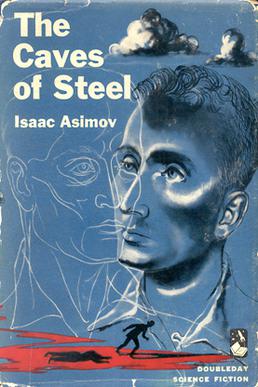

In 1953’s

In 1953’s  Neil Gaiman’s

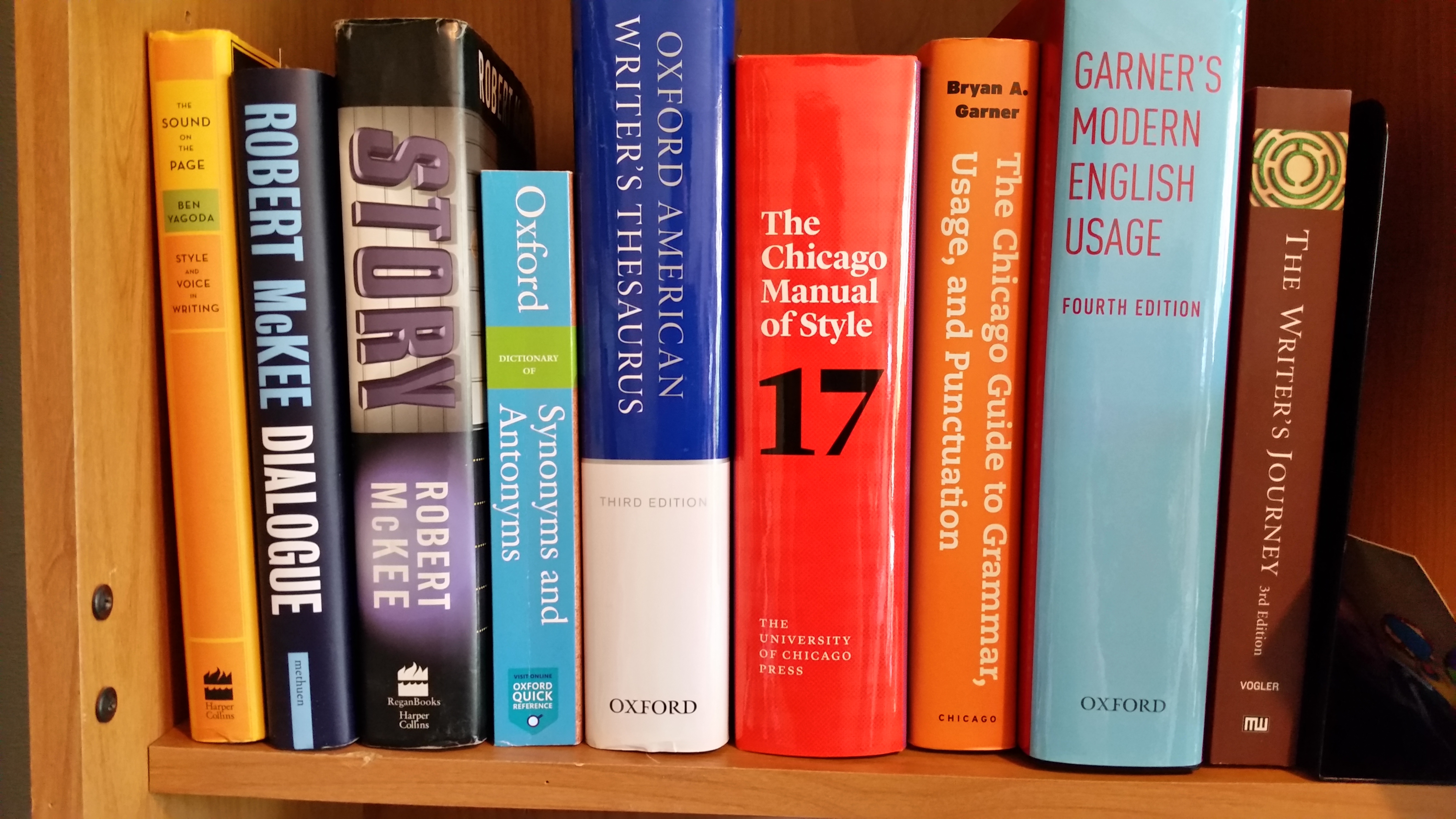

Neil Gaiman’s  Dedicated authors are driven to learn the craft of writing, and it is a quest that can take a lifetime. It is a journey that involves more than just reading “How to Write This or That Aspect of a Novel” manuals. Those are important and my library is full of them. But how-to manuals only offer up a part of the picture. The rest of the education is within each of us, an amalgamation of our life experiences and what we have learned along the way.

Dedicated authors are driven to learn the craft of writing, and it is a quest that can take a lifetime. It is a journey that involves more than just reading “How to Write This or That Aspect of a Novel” manuals. Those are important and my library is full of them. But how-to manuals only offer up a part of the picture. The rest of the education is within each of us, an amalgamation of our life experiences and what we have learned along the way. Authors write because we have a story to tell, one that might also embrace morality and the meaning of life. To that end, every word we put to the final product must count if our ideas are to be conveyed.

Authors write because we have a story to tell, one that might also embrace morality and the meaning of life. To that end, every word we put to the final product must count if our ideas are to be conveyed. It follows that certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. Code words are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One word, one packet of letters will serve many purposes and convey a myriad of mental images.

It follows that certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. Code words are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One word, one packet of letters will serve many purposes and convey a myriad of mental images. I want to avoid that sin in my work, but what are my code words? What words are being inadvertently overused as descriptors? A good way to discover this is to make a word cloud. The words that see the most screen time will be the largest.

I want to avoid that sin in my work, but what are my code words? What words are being inadvertently overused as descriptors? A good way to discover this is to make a word cloud. The words that see the most screen time will be the largest.  endured

endured Sometimes, the only thing that works is the brief image of a smile. Nothing is more boring than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I want to know what is happening inside our characters and can be put off by an exaggerated outward display.

Sometimes, the only thing that works is the brief image of a smile. Nothing is more boring than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I want to know what is happening inside our characters and can be put off by an exaggerated outward display. In creative writing, the apostrophe is a small morsel of punctuation that, on the surface, seems simple. However, certain common applications can be confusing, so as we get to those I will try to be as concise and clear as possible.

In creative writing, the apostrophe is a small morsel of punctuation that, on the surface, seems simple. However, certain common applications can be confusing, so as we get to those I will try to be as concise and clear as possible.