Two months ago, we began our series, Idea to Story. The previous eleven installments are listed below. We have created a sample story, a romantasy. We have met our protagonists and the ultimate antagonist. We know what their world is like and have given them a worthy quest, and we discovered what genre we are writing by paying attention to the tropes that arose as we were laying down the plot.

Now, we’re going to examine the themes that have emerged. We will strengthen the story arc and make the characters more vivid by ensuring a strong central theme is woven through the story.

Now, we’re going to examine the themes that have emerged. We will strengthen the story arc and make the characters more vivid by ensuring a strong central theme is woven through the story.

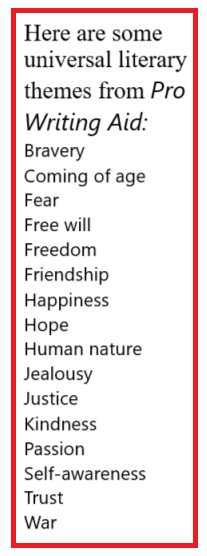

But first, what is a theme? It is an idea, an unspoken message that winds through the arc of the story and generates action. Themes are subtle but move the characters to action and define why the action happens. For an incredible list of themes, go to A Huge List of Common Themes – Literary Devices.

Before we talk about the themes we want to incorporate in our story, let’s look at how the master of themes, Henry James, wove them into his work.

Henry James is a 19th-century writer you might have heard of but never read. However, he can teach us so much about using a story’s themes to create memorable characters. You may be familiar with the titles of some of his works, such as The Turn of the Screw and The Golden Bowl. Filmmakers and playwrights are still turning his work into movies and plays.

Henry James is a 19th-century writer you might have heard of but never read. However, he can teach us so much about using a story’s themes to create memorable characters. You may be familiar with the titles of some of his works, such as The Turn of the Screw and The Golden Bowl. Filmmakers and playwrights are still turning his work into movies and plays.

Henry James was a master at writing one common theme into a story—lust. Lust for sex. Lust for money. Lust for control.

Lust for power.

Henry James wrote one of the most famous novellas ever published, the Turn of the Screw.

On the surface, the Turn of the Screw is a gothic horror story. The four main themes are the corruption of the innocent, the destructiveness of heroism, the struggle between good and evil, and the difference between reality and fantasy. A fifth theme is the perception of ghosts. Are the ghosts real or the projection of the governess’s madness?

However, there are several subthemes interwoven into the fabric of the narrative:

- Secrecy.

- Deception.

- The lust for control.

- Obsession.

What I take home from the longevity of Henry James’s work is this: find a strong theme and use it to underscore and support our characters’ motives.

So, now we know that literary themes are a pattern, a “melody” that recurs in varying forms throughout a story. They emphasize mood and shape the plot.

The main theme of our story is the struggle between good and evil. In Donovan’s well-planned manipulation of Kai under the guise of brotherly mentoring, we have the subthemes of deception and the corruption of the innocent. In Val and Kai, we have the dangers of ignorance and the subthemes of arrogance and class prejudice.

The main theme of our story is the struggle between good and evil. In Donovan’s well-planned manipulation of Kai under the guise of brotherly mentoring, we have the subthemes of deception and the corruption of the innocent. In Val and Kai, we have the dangers of ignorance and the subthemes of arrogance and class prejudice.

Our three main characters are people. In real life, people are a mix of good and bad at the same time. Some lean more toward good, others toward bad. Either way, their intentions are logical, and they desperately want what they think they deserve.

Most importantly, our characters lie to themselves about their own motives and obscure the truth behind other, more palatable truths. These unspoken truths are the themes we must weave into the fabric of our story by subtly showing a pattern.

Two themes we want to emphasize in Donovan are the desire for power and the use of fear as a means of control. However, at first, we want the tug-of-war for control of the child king, Edward, to be focused on the regents, Kai Voss and Valentine.

The story opens from Val’s point of view, so we lean a bit toward her. But not entirely, as Kai’s chapter shows he has good intentions.

By hinting at the pattern of Donvan’s actions in the first quarter of the book, his lust for power becomes clear. We hope to create in the reader a sense of helplessness to stop what we see coming. This is emphasized as clues appear, indicating that Val and Kai are acting on misinformation that is deliberately fed to them.

Once Val and Kai find themselves in the dungeon, new themes will join the story. Both are in their mid-thirties and are established and respected in their respective peer groups. However, both must have a coming-of-age arc. Despite their apparent adulthood, they each have a lot to learn about real life.

But what about young King Edward? For Val and Kai, the theme of parental love is shown in their actions of caring for him from the beginning. While he is not their child, he is in their care and both love him as if he were their son and are secretly jealous of each other. They have differing goals for him, which causes friction, but the reader doesn’t doubt their sincere love for the boy.

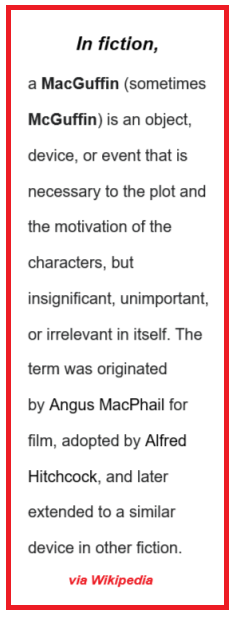

Edward is sickly, cursed with a wasting disease. All through this tale, he has been a McGuffin, the object of the quest and a pawn in Donovan’s game of power. His character arc is limited because he is bedridden and unaware of the war for control centered on him.

Edward is sickly, cursed with a wasting disease. All through this tale, he has been a McGuffin, the object of the quest and a pawn in Donovan’s game of power. His character arc is limited because he is bedridden and unaware of the war for control centered on him.

When she wakes up in the dungeon, Val realizes who truly set the curse on Edward and who murdered the boy’s parents in the first place. She realizes that if she can’t rescue Edward, Donovan’s curse will kill him, and Donovan will become king. She is miserably aware that she will need a wizard to counter Donovan’s sorcery. Unfortunately, the only sorcerer she has access to is Kai, which means she must rescue him first, something she despises having to do.

Conversely, Kai is glad to be free but not pleased that it is Valentine who has rescued him. He doubts her motives and refuses to believe his brother betrayed him, until they overhear the guards talking.

Val and Kai must learn to work together. As they do, the theme of romantic love will emerge.

What other themes might emerge as we write our story? How will we recognize and underscore the patterns, the melodies that appear in the narrative?

This is where writing becomes a craft, and to excel at any craft, we must work at it.

Thank you for sticking with me as we worked our way through this long and involved process of taking an idea for a story and building the characters, the world, and the plot.

While the story of Val and Kai is just a sample plot for demonstration, I have used these weeks to reexamine the different aspects of my current work in progress. Talking my way through a plot with my friends really helps, so thank you!

Previous in this series:

Idea to story part 2: thinking out loud #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 3: plotting out loud #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 4 – the roles of side characters #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 5 – plotting treason #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 6 – Plotting the End #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 7 – Building the world #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 8 – world-building and society #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 9 – technology and world-building #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to Story part 10 – science and magic as world-building #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 11: Genre and expected tropes #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

For the last few weeks, many writers have been pouring the words onto paper, trying to get 50,000 words in 30 days. Some have written themselves into a corner and have discovered there is no graceful way out.

For the last few weeks, many writers have been pouring the words onto paper, trying to get 50,000 words in 30 days. Some have written themselves into a corner and have discovered there is no graceful way out. I hate it when I find myself at the point where I am fighting the story, forcing it onto paper. It feels like admitting defeat to confess that my story has taken a wrong turn so early on, and I hate that feeling. Fortunately, I knew by the 40,000-word point that last year’s story arc had gone so far off the rails that there was no rescuing it.

I hate it when I find myself at the point where I am fighting the story, forcing it onto paper. It feels like admitting defeat to confess that my story has taken a wrong turn so early on, and I hate that feeling. Fortunately, I knew by the 40,000-word point that last year’s story arc had gone so far off the rails that there was no rescuing it. The sections I cut weren’t a waste, they were a detour. In so many ways, that sort of thing is why it takes me so long to write a book—each story contains the seeds of more stories.

The sections I cut weren’t a waste, they were a detour. In so many ways, that sort of thing is why it takes me so long to write a book—each story contains the seeds of more stories. Sometimes, something different happens. In 2019, I realized the novel I was writing is actually two books worth of story. The first half is the protagonist’s personal quest and is finished. The second half resolves the unfinished thread of what happened to the antagonist and is what I am currently working on. Both halves of the story have finite endings, so for the paperback version, I will break it into two novels. That will keep my costs down.

Sometimes, something different happens. In 2019, I realized the novel I was writing is actually two books worth of story. The first half is the protagonist’s personal quest and is finished. The second half resolves the unfinished thread of what happened to the antagonist and is what I am currently working on. Both halves of the story have finite endings, so for the paperback version, I will break it into two novels. That will keep my costs down. For those of you who are curious—I have the attention span of a sack full of squirrels. Proof of that can be found in the 4 novels currently in progress that are set in that world, each at different eras of the 3000-year timeline, each in various stages of completion.

For those of you who are curious—I have the attention span of a sack full of squirrels. Proof of that can be found in the 4 novels currently in progress that are set in that world, each at different eras of the 3000-year timeline, each in various stages of completion. think of

think of  I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them. If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in  Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice. Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

Pantser vs. Plotter

Pantser vs. Plotter  Planster

Planster