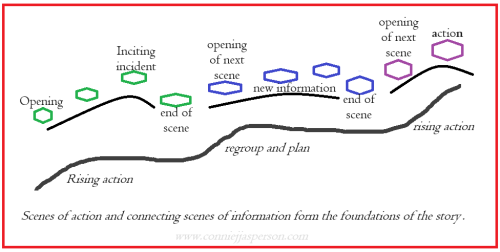

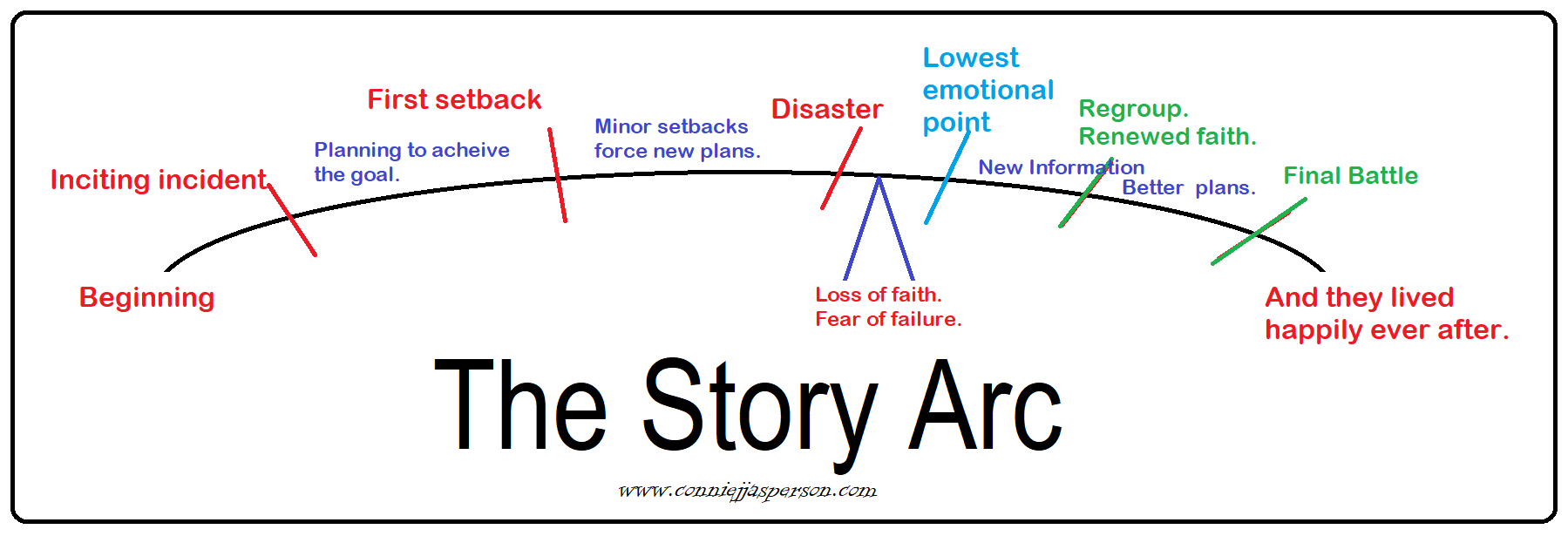

All writers begin as readers. As we read, we see an arc to the overall novel. It starts with exposition, where we introduce our characters and their situation. Then, we get to the rising action, where complications for the protagonist are introduced. The middle section is the action’s high point, the narrative’s turning point.

After we survive the middle crisis, we have falling action. We receive the crucial information, the characters regroup, and we experience the unfolding of events leading to the conclusion. The protagonist’s problems are resolved, and we (the readers) are offered a good ending and closure.

After we survive the middle crisis, we have falling action. We receive the crucial information, the characters regroup, and we experience the unfolding of events leading to the conclusion. The protagonist’s problems are resolved, and we (the readers) are offered a good ending and closure.

I think of scenes as micro-stories. Each one forms an arch of rising action followed by a conclusion, creating a stable structure that will support the overall arc of the plot. In my mind, novels are like Gothic Cathedrals–small arches built of stone supporting other arches until you have a structure that can withstand the centuries. Each scene is a tiny arc that supports and strengthens the construct that is our plot.

Each scene has a job and must lead to the next. If we do it right, the novel will succeed.

The key difference in the arc of the scene vs. the overall arc of the novel is this: the end of the scene is the platform from which your next scene launches. Each scene begins at a slightly higher point on the novel’s plot arc than the previous scene, pushing the narrative toward its ultimate conclusion.

These small arcs of action, reaction, and calm push the plot and ensure it doesn’t stall. Each scene is an opportunity to ratchet up the tension and increase the overall conflict that drives the story.

These small arcs of action, reaction, and calm push the plot and ensure it doesn’t stall. Each scene is an opportunity to ratchet up the tension and increase the overall conflict that drives the story.

My writing style in the first stages is more like creating an extensive and detailed outline. I lay down the skeleton of the tale, fleshing out what I can as I go. But there are significant gaps in this early draft of the narrative.

So, once the first draft is finished, I flesh out the story with visuals and action. Those are things I can’t focus on in the first draft, but I do insert notes to myself, such as:

- Fend off the attack here.

- Contrast tranquil scenery with turbulent emotions here.

My first drafts are always rough, more like a series of events and conversations than a novel. I will stitch it all together in the second draft and fill in the plot holes.

So, how do I link these disparate scenes together? Conversations and internal dialogs make good transitions, propelling the story forward to the next scene. A conversation can give the reader perspective if there is no silent witness (an omniscient presence). This view is needed to understand the reason for events.

Transition scenes must also have an arc supporting the cathedral that is our novel. They will begin, rise to a peak as the necessary information is discussed, and ebb when the characters move on.

Transition scenes must also have an arc supporting the cathedral that is our novel. They will begin, rise to a peak as the necessary information is discussed, and ebb when the characters move on.

Transition scenes inform the reader and the characters, offering knowledge we all must know to understand the forthcoming action.

A certain amount of context can arrive through internal monologue. However, I have two problems with long mental conversations:

- If you choose to use italics to show characters’ thoughts, be aware that long sections of leaning letters are challenging to read, so keep them brief.

- Internal dialogue is frequently a thinly veiled cover for an info dump.

An example of this is a novel I recently waited nearly a year for, written by a pair of writers whose work I have enjoyed over the years. I was seriously disappointed by it.

The protagonist’s mental ramblings comprise the first two-thirds of the novel. Fortunately, the authors didn’t use italics for the main character’s mental blather.

This exhausting mental rant contained very little critical knowledge. Ninety percent of what the man ruminated on was fluff—it was all background covered in the broader series and didn’t push the story forward. At the midpoint, I considered not finishing the book.

Plots are driven by an imbalance of power. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information.

Plots are driven by an imbalance of power. The dark corners of the story are illuminated by the characters who have critical knowledge. This is called asymmetric information.

The characters must work with a limited understanding of the situation because asymmetric information creates tension. A lack of knowledge creates a crisis.

It’s tempting to waffle on but a conversation scene should be driven by the fact that one person has knowledge the others need. Idle conversations can be had anywhere, and readers don’t want to read about them. Characters should discuss things that advance the plot in such a way that they illuminate their personality.

The reader must get answers at the same time as the other characters, gradually over the length of a novel.

I struggle with this, too. Dispersing small but necessary bits of info at the right moment is tricky because I know it all and must fight the urge to share it too early. Hopefully, all these bumps will have been smoothed out by the end of my second draft.

When we write a story, no matter the length, we hope the narrative will keep our readers interested until the end of the book. We lure readers into the scene and reward them with a tiny dose of new information.

When we write a story, no matter the length, we hope the narrative will keep our readers interested until the end of the book. We lure readers into the scene and reward them with a tiny dose of new information.

I have no idea whether the novel I’m working on today will be an engaging story for a reader or not. But I’m enjoying writing it.

And that is what writing should be about: writing the story you want to read.

In my work, the first draft is really more of an expanded outline, a series of scenes that have characters doing things. But those scenes need to be connected so each flows naturally into the next without jarring the reader out of the narrative.

In my work, the first draft is really more of an expanded outline, a series of scenes that have characters doing things. But those scenes need to be connected so each flows naturally into the next without jarring the reader out of the narrative. We are always told, “Don’t waste words on empty scenes.” I find this part of the revision process the most difficult. Frankly, I have a million words at my disposal, and wasting them is my best skill.

We are always told, “Don’t waste words on empty scenes.” I find this part of the revision process the most difficult. Frankly, I have a million words at my disposal, and wasting them is my best skill. If you ask a reader what makes a memorable story, they will tell you that the emotions it evoked are why they loved that novel. They were allowed to process the events, given a moment of rest and reflection between the action. Our characters can take a moment to think, but while doing so, they must be transitioning to the next scene.

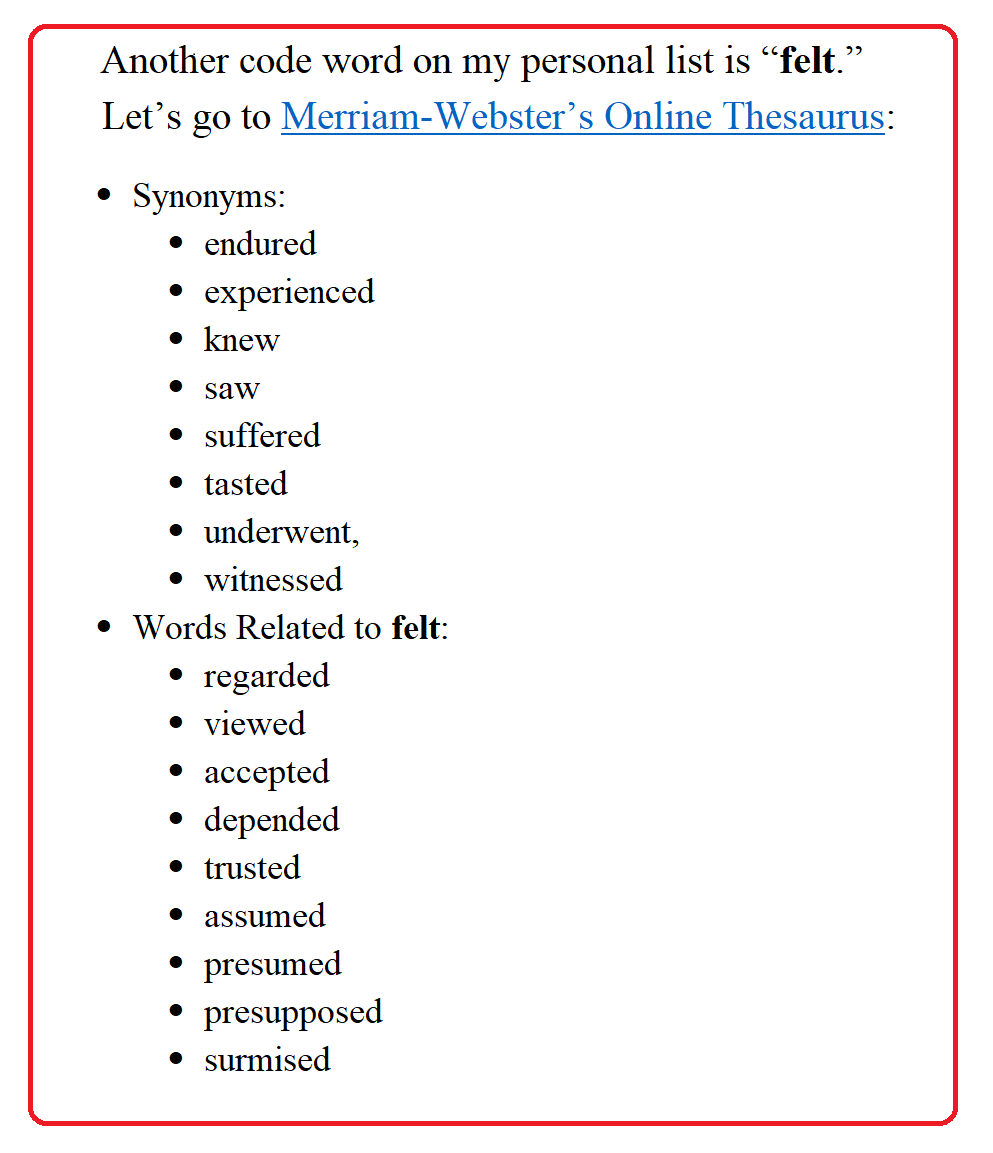

If you ask a reader what makes a memorable story, they will tell you that the emotions it evoked are why they loved that novel. They were allowed to process the events, given a moment of rest and reflection between the action. Our characters can take a moment to think, but while doing so, they must be transitioning to the next scene. Visual Cues: In my own work, when I come across the word “smile” or other words conveying a facial expression or character’s mood, it sometimes requires a complete re-visualization of the scene. I’m forced to look for a different way to express my intention, which is a necessary but frustrating aspect of the craft.

Visual Cues: In my own work, when I come across the word “smile” or other words conveying a facial expression or character’s mood, it sometimes requires a complete re-visualization of the scene. I’m forced to look for a different way to express my intention, which is a necessary but frustrating aspect of the craft. We add the details when we begin the revision process. One of the elements we look for in our narrative is pacing, or how the story flows from the opening scene to the final pages.

We add the details when we begin the revision process. One of the elements we look for in our narrative is pacing, or how the story flows from the opening scene to the final pages. This string of scenes is like the ocean. It has a kind of rhythm, a wave action we call pacing. Pacing is created by the way an author links actions and events, stitching them together with quieter scenes: transitions.

This string of scenes is like the ocean. It has a kind of rhythm, a wave action we call pacing. Pacing is created by the way an author links actions and events, stitching them together with quieter scenes: transitions.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals. With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals. With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.

Code words are the author’s first draft

Code words are the author’s first draft  Thought (Introspection):

Thought (Introspection): That is true of every aspect of a scene—it must reveal something we didn’t know and push the story forward toward something we can’t quite see.

That is true of every aspect of a scene—it must reveal something we didn’t know and push the story forward toward something we can’t quite see.![Tavern of the Crescent Moon by Jan Miense Molenaer [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/tavern_of_the_crescent_moon_jan_miense_molenaer.jpg?w=300)

![Peasant Wedding by David Teniers the Younger [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/david_teniers_de_jonge_-_peasant_wedding_1650.jpg?w=300)

![Autumn on Greenwood Lake, ca. 1861, by Jasper Francis Cropsey [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/jasper_francis_cropsey_-_autumn_on_greenwood_lake_-_google_art_project.jpg?w=300)

![I, Sailko [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/benozzo_gozzoli_corteo_dei_magi_1_inizio_1459_51.jpg?w=198)

![Sir Galahad, George Frederic Watts [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/220px-sir_galahad_watts.jpg?w=147)