Over the next few months, authors embarking on their first NaNoWriMo will hear many rules about the craft of writing. Some will be good, and some will lead to later problems. I suggest you write the story as it falls out of your head during NaNoWriMo. Don’t worry too much about the rules until you get to the revision stage.

Getting those ideas out of your head now is what is important. The bloopers and grammar hiccups can all be ironed out in the second draft.

Getting those ideas out of your head now is what is important. The bloopers and grammar hiccups can all be ironed out in the second draft.

The common axioms of writing exist because writing a story that others can enjoy involves learning grammar rules, developing a broader vocabulary, developing characters, building worlds, etc.

However—some commonly repeated mantras of writing advice have the potential to backfire. An author with too rigid a view of these sayings will write lifeless prose, narratives an algorithm could produce.

The worst rules, in my opinion, are these three:

- Remove all adverbs and adjectives. This advice is complete crap. Use common sense, and don’t use unnecessary modifiers.

- Don’t use speech tags. What? Who said that, and why are there no speech tags in this nonsense?

- Show, Don’t Tell. Don’t Ever Don’t do it! Oh, dear. What an amazing gymnastic routine your face is experiencing.

Nothing is more disgusting than a scene where a person’s facial expressions are described in minute detail.

Yes, we do need to show moods, and some physical description is necessary. Lips stretch into smiles, and eyebrows draw together. Still, they are not autonomous and don’t operate independently of the character’s emotional state. The musculature of the face is only part of the signals that reveal the character’s interior emotions.

Yes, we do need to show moods, and some physical description is necessary. Lips stretch into smiles, and eyebrows draw together. Still, they are not autonomous and don’t operate independently of the character’s emotional state. The musculature of the face is only part of the signals that reveal the character’s interior emotions.

Another extreme is when the author leans too heavily on the internal, describing the stomach-churning, gut-wrenching shock and wide-eyed trembling of hands in such detail the reader feels queasy and puts the book in the trash.

Which reminds me—don’t forget the weak-kneed nausea.

For me, the most challenging part of revising a manuscript is balancing the visual indicators of emotion with the more profound internal clues. This is something that really only takes shape to my satisfaction through multiple drafts.

- Write what you know, and don’t dare to write something you don’t. In other words, what they’re saying is don’t use your imagination.

True, you should be careful when writing a real-world ethnicity you don’t have a personal experience of. If your heart is set on that story and only that story, you might want to consult someone from that culture. 5 Tips for Avoiding Cultural Appropriation in Fiction | Proofed’s Writing Tips

But in fantasy, while our life experiences shape our writing, our imagination is the story’s fuel and source. J.R.R. Tolkien understood senseless conflicts and total warfare—because he had experienced it. His books detail his view of the utter devastation of war but are set in a fantasy environment and feature elves and orcs. (Those are two races that don’t abound in England, at least not that I’ve heard.)

Another unreservedly silly mantra is this one:

- If you’re bored with your story, your reader will be too.

That’s NOT true. You have spent months immersed in that story, years even. You know it inside and out, but your reader doesn’t. Set it aside and come back to it a month or more later. You’ll fall in love with it again.

Commonly discussed writing proverbs go on and on.

- Kill your darlings.

Indeed, we shouldn’t be married to our favorite prose or characters. Sometimes, we must cut a sentence, a paragraph, a chapter, or even a character we love because it no longer fits the story. But have a care – people read for pleasure and because they love good prose. If it works, keep it.

- Cut all exposition.

The timing of when we insert the exposition into the narrative is crucial. A story must be about the characters, the conflict, and the resolution. The reader wants to know what the characters know. But they only need that knowledge when it becomes necessary for the plot to move forward. They don’t want information dumped on them.

Bad advice is good advice taken to an extreme. But all writing advice has roots in truth. So, when it comes to making revisions, consider these suggestions:

Bad advice is good advice taken to an extreme. But all writing advice has roots in truth. So, when it comes to making revisions, consider these suggestions:

- Overuse of adverbs fluffs up the prose and ruins the taste of an author’s work. Don’t get too artful.

- Too many speech tags, especially odd and bizarre ones, can stop the eye. When the characters snort, hiss, and exclaim their dialogue, I will put the book down and never pick it up again. My favorite authors seem to stick to common tags like said and replied. Those tags blend into the background.

- Too much telling takes the adventure out of the reading experience. Too much showing is tedious and can be disgusting. It takes effort to find that happy medium, but writing is work.

- Know what you are writing about. Research your subject and, if necessary, interview people in that profession. Readers often know more than you do about certain things.

Education doesn’t happen overnight. I’ve been studying the craft for over twenty years and always learn something new. Unless an author is fortunate enough to have a formal education in the subject, we must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides to learn the many nuances of the writing craft.

I buy books about the craft of writing modern, 21st-century genre fiction and rely on the advice offered by the literary giants of the past. I seek a rounded view of crafting prose and look for other tools that I can use to improve my writing. I think this makes me a better, more informed reader. (My ego speaking.)

I recommend investing in a grammar book, depending on whether you use American or UK English. These books will answer your questions, and you won’t be in doubt about how to use the standard punctuation readers expect to see.

I recommend investing in a grammar book, depending on whether you use American or UK English. These books will answer your questions, and you won’t be in doubt about how to use the standard punctuation readers expect to see.

The Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation (if you use American English)

OR

The Oxford A – Z of Grammar and Punctuation (if you use UK English)

Both American and UK writers should invest in:

The Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms (UK and American English). This will increase your vocabulary and help you avoid repetition and leaning on crutch words.

There are many other books on the craft of writing, but a grammar guide and a dictionary of synonyms will take you a long way.

I recommend checking out the NaNoWriMo Store, which offers several books to help you get started. The books available there have good advice for beginners, whether you participate in November’s writing rumble or want to write at your own pace.

I recommend checking out the NaNoWriMo Store, which offers several books to help you get started. The books available there have good advice for beginners, whether you participate in November’s writing rumble or want to write at your own pace.

Other books on craft that I own and recommend:

- Damn Fine Story, by Chuck Wendig

- Dialogue, by Robert McKee

- Steering the Craft: A Twenty-First-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story, by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Story, by Robert McKee

- The Emotion Thesaurusby Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi, and I also have all the companion books in that series.

- The Writer’s Journey, by Christopher Vogler

- VERBALIZE by Damon Suede and its companion book, Activate.

I study the craft of writing because I love it, and I apply the proverbs and rules of advice gently. Whether my work is good or bad—I don’t know. But I write the stories I want to read, so I am writing for a niche audience of one: me.

I study the craft of writing because I love it, and I apply the proverbs and rules of advice gently. Whether my work is good or bad—I don’t know. But I write the stories I want to read, so I am writing for a niche audience of one: me.

Be brave. Write your novel during NaNoWriMo and worry about fine-tuning it later. That’s what revisions are all about.

Magic or the supernatural are core plot elements in most of my work. I see them as part of the world, the way the Alps were a core plot element in the story of the

Magic or the supernatural are core plot elements in most of my work. I see them as part of the world, the way the Alps were a core plot element in the story of the  Hannibal paid a heavy price for bringing his superweapons (elephants) to the battle. The ability to use magic should come at some cost, either physical or emotional. Or it should require coins or theft to acquire magic artifacts.

Hannibal paid a heavy price for bringing his superweapons (elephants) to the battle. The ability to use magic should come at some cost, either physical or emotional. Or it should require coins or theft to acquire magic artifacts.  It’s fair to write stories where magic is learned through spells if one has an inherent gift, and it’s also fair to require a wand. That is how magic was always done in traditional fairy tales and J.K. Rowling took those worn-out tropes and made them new and wonderful.

It’s fair to write stories where magic is learned through spells if one has an inherent gift, and it’s also fair to require a wand. That is how magic was always done in traditional fairy tales and J.K. Rowling took those worn-out tropes and made them new and wonderful. I can suspend my disbelief when magic and supernatural abilities are only possible if certain conditions have been met. The best tales featuring characters with paranormal skills occur when the author creates a system that regulates what the characters can NOT do.

I can suspend my disbelief when magic and supernatural abilities are only possible if certain conditions have been met. The best tales featuring characters with paranormal skills occur when the author creates a system that regulates what the characters can NOT do. A crucial reason for establishing the science of magic and the paranormal before randomly casting spells or flinging fire is this: the use of these gifts impacts the wielder’s companions and influences the direction of the plot, creating tension.

A crucial reason for establishing the science of magic and the paranormal before randomly casting spells or flinging fire is this: the use of these gifts impacts the wielder’s companions and influences the direction of the plot, creating tension. or the paranormal in your NaNo novel, how can you take these common tropes in a new direction?

or the paranormal in your NaNo novel, how can you take these common tropes in a new direction? First, what sort of world is your real life set in? When you look out the window, what do you see? Close your eyes and picture the place where you are at this moment. With your eyes still closed, tell me what it’s like. If you can describe the world around you, you can create a world for your characters.

First, what sort of world is your real life set in? When you look out the window, what do you see? Close your eyes and picture the place where you are at this moment. With your eyes still closed, tell me what it’s like. If you can describe the world around you, you can create a world for your characters. What does the outdoor world look and smell like? Is it damp and earthy, or dry and dusty? Is there the odor of fallen leaves moldering in the gutters? Or have we wandered too near the chicken coop? (Eeew … get it off my shoe!) If an author can inject enough sight, sound, and scent into a fantasy or sci-fi setting, the world will feel solid when I read it.

What does the outdoor world look and smell like? Is it damp and earthy, or dry and dusty? Is there the odor of fallen leaves moldering in the gutters? Or have we wandered too near the chicken coop? (Eeew … get it off my shoe!) If an author can inject enough sight, sound, and scent into a fantasy or sci-fi setting, the world will feel solid when I read it.

What about transport? How do people and goods go from one place to another?

What about transport? How do people and goods go from one place to another? Names and directions might drift and change as you write your first draft. Also, if they’re invented words, consider writing them close to how they are pronounced.

Names and directions might drift and change as you write your first draft. Also, if they’re invented words, consider writing them close to how they are pronounced. When someone asks me what a book I wrote is about, my mind grinds to a halt as I try to decide what to say. I could give them the rundown of the plot, which is the arc of events the characters experience.

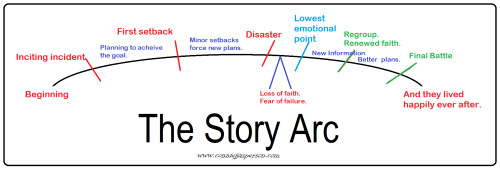

When someone asks me what a book I wrote is about, my mind grinds to a halt as I try to decide what to say. I could give them the rundown of the plot, which is the arc of events the characters experience. The story writes itself when I begin with a strong theme and solid characters. A 19th-century writer many have heard of but never read,

The story writes itself when I begin with a strong theme and solid characters. A 19th-century writer many have heard of but never read,  When

When Love is only one theme, yet it has so many facets. Other themes abound, large central concepts that build tension within the narrative.

Love is only one theme, yet it has so many facets. Other themes abound, large central concepts that build tension within the narrative. Sometimes, we can visualize a complex theme but can’t explain it. If we can’t explain it, how do we show it? Consider the theme of “grief.” It is a common theme that can play out against any backdrop, whether sci-fi or reality based, where humans interact on an emotional level.

Sometimes, we can visualize a complex theme but can’t explain it. If we can’t explain it, how do we show it? Consider the theme of “grief.” It is a common theme that can play out against any backdrop, whether sci-fi or reality based, where humans interact on an emotional level. Even if you don’t have an idea of what you want to write, it’s time to go out to

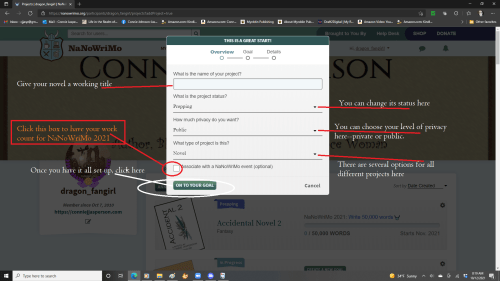

Even if you don’t have an idea of what you want to write, it’s time to go out to  Once there, create a profile. You don’t have to get fancy unless you are bored and feeling hypercreative.

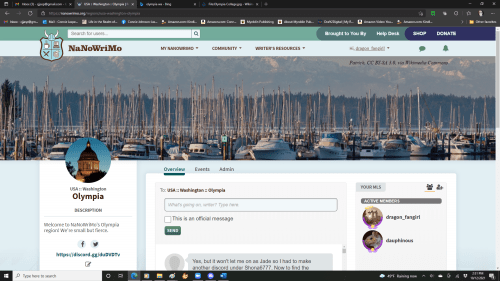

Once there, create a profile. You don’t have to get fancy unless you are bored and feeling hypercreative. You can play around with your personal page a little to get used to it. I use my NaNoWriMo avatar and name as my

You can play around with your personal page a little to get used to it. I use my NaNoWriMo avatar and name as my  Next, check out the community tabs. If you are in full screen, the tabs will be across the top. If you have the screen minimized, the button for the dropdown menu will be in the upper right corner and will look like the blue/green and black square to the right of this paragraph.

Next, check out the community tabs. If you are in full screen, the tabs will be across the top. If you have the screen minimized, the button for the dropdown menu will be in the upper right corner and will look like the blue/green and black square to the right of this paragraph. You may find the information you need in one of the many forums listed here.

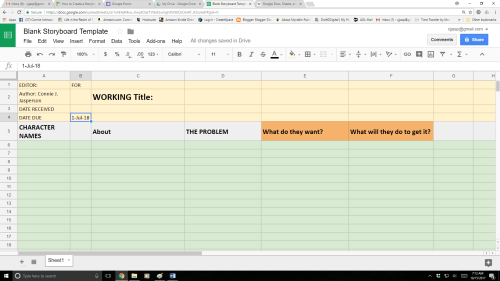

You may find the information you need in one of the many forums listed here. Make a master file folder that is just for your writing. I write professionally, so my files are in a master file labeled Writing.

Make a master file folder that is just for your writing. I write professionally, so my files are in a master file labeled Writing. Give your document a label that is simple and descriptive. My NaNoWriMo manuscript will be labeled: Stowe_Bridge_NaNoWriMo_2023.

Give your document a label that is simple and descriptive. My NaNoWriMo manuscript will be labeled: Stowe_Bridge_NaNoWriMo_2023. This year we will have write-ins at the local library. The authors in our region will come together and write for two hours and support each other’s journey. We will also meet via the miracle of the internet, using Discord and Zoom. My co-ML and I are finalizing a schedule for November.

This year we will have write-ins at the local library. The authors in our region will come together and write for two hours and support each other’s journey. We will also meet via the miracle of the internet, using Discord and Zoom. My co-ML and I are finalizing a schedule for November. I am the queen of front-loading too much history in my first drafts. Fortunately, my writer’s group has an unerring eye for where the story really begins.

I am the queen of front-loading too much history in my first drafts. Fortunately, my writer’s group has an unerring eye for where the story really begins. You have done some prep work for character creation, so Tam is your friend. You know his backstory, who he is attracted to (men, women, none, or both), how handsome he is, and his personal history. But none of this matters to the reader in the opening pages. The reader only wants to know what will happen next.

You have done some prep work for character creation, so Tam is your friend. You know his backstory, who he is attracted to (men, women, none, or both), how handsome he is, and his personal history. But none of this matters to the reader in the opening pages. The reader only wants to know what will happen next. Tam and Dagger will tell you what events and roadblocks must happen to them between their arrests and the final victory. This knowledge will emerge from your imagination as you write your way through this first draft.

Tam and Dagger will tell you what events and roadblocks must happen to them between their arrests and the final victory. This knowledge will emerge from your imagination as you write your way through this first draft. Tam will find this information out as the story progresses and we will learn it as he does. With that knowledge, he will realize his fate is sealed—he’s doomed no matter what. But it fires him with the determination that if he goes down, he will take the Warlock Prince and his corrupt Cardinal, with him.

Tam will find this information out as the story progresses and we will learn it as he does. With that knowledge, he will realize his fate is sealed—he’s doomed no matter what. But it fires him with the determination that if he goes down, he will take the Warlock Prince and his corrupt Cardinal, with him.

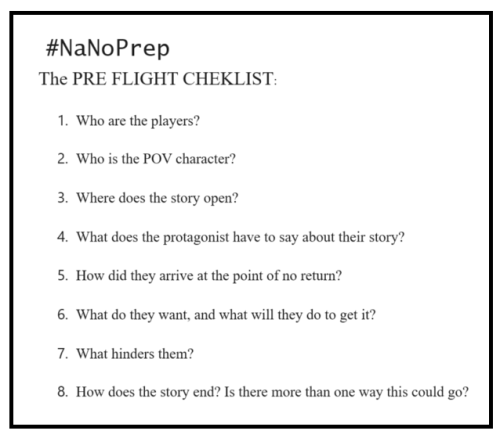

Now, we’re going to hear what our characters have to say about what their story might be.

Now, we’re going to hear what our characters have to say about what their story might be. An important point to remember is that no matter how decent they are, people lie to themselves about their motives. It’s human nature to obscure truths we don’t want to face behind other, more palatable truths. Those secrets will emerge as you write.

An important point to remember is that no matter how decent they are, people lie to themselves about their motives. It’s human nature to obscure truths we don’t want to face behind other, more palatable truths. Those secrets will emerge as you write. In my most recent book,

In my most recent book,  I’m going off-topic here for a moment. While the death of a character stirs the emotions, it must be a crucial turning point in that story. It must be planned and be the impetus that changes everything. The death of a character must drive the remaining characters to achieve greatness.

I’m going off-topic here for a moment. While the death of a character stirs the emotions, it must be a crucial turning point in that story. It must be planned and be the impetus that changes everything. The death of a character must drive the remaining characters to achieve greatness. Unless, of course, you are writing paranormal fantasy. Death and resurrection may be the whole point if that’s the case.

Unless, of course, you are writing paranormal fantasy. Death and resurrection may be the whole point if that’s the case. If your employment isn’t a work-from-home job, using the note-taking app on your cellphone to take notes during business hours will be frowned upon. I suggest keeping a pocket-sized notebook and pencil or pen to write those ideas down as they come to you.

If your employment isn’t a work-from-home job, using the note-taking app on your cellphone to take notes during business hours will be frowned upon. I suggest keeping a pocket-sized notebook and pencil or pen to write those ideas down as they come to you. We talked about getting a start on our characters in Monday’s post. Today, we’re going to visualize the place where our proposed novel is set, the place where the story opens.

We talked about getting a start on our characters in Monday’s post. Today, we’re going to visualize the place where our proposed novel is set, the place where the story opens. All worldbuilding must show a world that feels as natural to the reader as their native environment. I used the forests and lowlands of Western Washington State as my template. The entire series evolved out of three paragraphs that answered the following question:

All worldbuilding must show a world that feels as natural to the reader as their native environment. I used the forests and lowlands of Western Washington State as my template. The entire series evolved out of three paragraphs that answered the following question:

Seagulls are a good example of what could happen. They fly and do their business while on the wing, and sometime find enjoyment in “bombing” windshields.

Seagulls are a good example of what could happen. They fly and do their business while on the wing, and sometime find enjoyment in “bombing” windshields. Some of us (Me! Me!) will make pencil-sketched maps of our fantasy world or the sci-fi setting. I find that maps are excellent brainstorming tools for when I can’t quite jostle a plot loose. It’s a form of doodling, a kind of mind wandering, and helps me find creative solutions to minor obstacles.

Some of us (Me! Me!) will make pencil-sketched maps of our fantasy world or the sci-fi setting. I find that maps are excellent brainstorming tools for when I can’t quite jostle a plot loose. It’s a form of doodling, a kind of mind wandering, and helps me find creative solutions to minor obstacles.

No matter how many characters you think are involved, one will stand out. That person will be the protagonist.

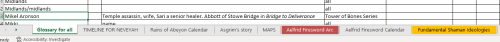

No matter how many characters you think are involved, one will stand out. That person will be the protagonist. Once I know the basic plot, I make a page in my workbook with a bio of each character, a short personnel file. Sometimes, I include images of RPG characters or actors who most physically resemble them and who could play them well—but this is only to cement them in my mind.

Once I know the basic plot, I make a page in my workbook with a bio of each character, a short personnel file. Sometimes, I include images of RPG characters or actors who most physically resemble them and who could play them well—but this is only to cement them in my mind. Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as more intense than one whose name starts with a soft sound. It’s a little thing, but it is something to consider when conveying personalities.

Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as more intense than one whose name starts with a soft sound. It’s a little thing, but it is something to consider when conveying personalities. Every year I participate in

Every year I participate in  Who are the players?

Who are the players? Characters usually arrive in my imagination as new acquaintances inhabiting a specific environment. That world determines the genre.

Characters usually arrive in my imagination as new acquaintances inhabiting a specific environment. That world determines the genre.