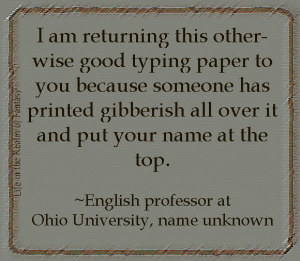

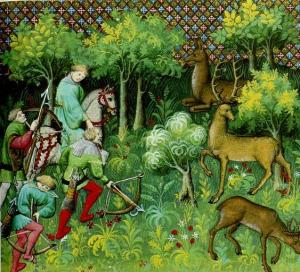

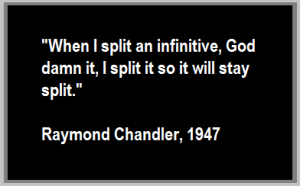

Russian Forest in medieval France (1405-1410) Gaston Phoebus

I have a great deal of interest in Medieval history because I have ancestors who lived then. I’m not bragging–everyone who is alive today is here because one or two ancestors survived the Dark Ages long enough to leave behind a child who did the same.

Life was perilous, even if you grew up in a fairly sheltered environment. No one was exempt from disease–even kings regularly died young from plagues and injuries. Regardless of their personal safety, medieval kings were forced to go to war in person. They did this for several reasons.

- The only way for the monarch to know what was actually happening on the battlefront was to be there

- It was expected that a monarch should understand the art of warfare and be proficient as a warrior. He was responsible for winning or losing the battle.

During the Dark Ages, official news was delivered by a royal messenger and read aloud in church or in the market.

During the Dark Ages, official news was delivered by a royal messenger and read aloud in church or in the market.

Messengers were a permanent fixture on the royal payroll. They were dedicated and well-paid to travel the kingdom continuously, carrying the king’s word. In medieval England, kings did not stay in London. Instead, they traveled all over their lands and the noble families were required to feed and house them at great expense. Their gypsy-like existence kept the messengers busy.

Wars were expensive. Henry VIII’s habit of medieval couch-surfing at the country homes of his noble courtiers was a great way for an impoverished king and his entourage to live well and cheaply, conserving the cash to pay for the troops. But it also meant that an organized and efficient messenger service was required to ensure that correspondence to and from the king: royal letters, grants, patents, and such, arrived at their intended destinations.

Tancred, Count of Lecce, King of Sicily via Wikimedia

In the year 1190, when my direct maternal ancestor, Tancred, King of Sicily, faced Richard I of England, he was limited to what information a messenger could convey. Thus, their battles were fought in person and so were their negotiations.

These were not native Italians–the original Tancred of Hauteville (980 – 1041) was an 11th-century Norman and a minor baron of Normandy about whom little is known, other than eight of his twelve sons joined the crusades and became kings of southern Italy in the process.

So his illegitimate great-grandson, King Tancred, and King Richard the Lionhearted were Norman kings, squabbling over what was left of the Holy Land and the Mediterranean at the end of the crusades. However, Tancred was born and raised there so he was a third generation Sicilian, being the out-of-wedlock son of Roger III, the Norman duke of Apulia and Emma of Lecce, who was married to Ruggero III de Hauteville.

Quote from Wikipedia: “In 1190 Richard I of England arrived in Sicily at the head of a large crusading army on its way to the Holy Land. Richard immediately demanded the release of his sister, William II’s wife Joan, imprisoned by Tancred in 1189, along with every penny of her dowry and dower. He also insisted that Tancred fulfill the financial commitments made by William II to the crusade. When Tancred balked at these demands, Richard seized a monastery and the castle of La Bagnara.” (end quoted text)

Richard I Google Art Project via Wikimedia

Richard was joined in Sicily by the French crusading army, led by his soon-to-be-former friend, King Philip II of France. The presence of two foreign armies highly aggravated the local citizens who, rightfully, demanded the foreigners leave their island.

Ever the good guest, King Richard responded by attacking Messina, which he captured on 4 October 1190. Once the city had been looted and burned, Richard established his base there and decided to stay the winter—after all, winters in Sicily are a bit more pleasant than those in Normandy.

But what’s a little looting and pillaging among friends? According to Wikipedia:

“Richard remained at Messina until March 1191, when Tancred finally agreed to a treaty. According to the treaty’s main terms:

- Joan was to be released, receiving her dower along with the dowry.

- Richard and Philip recognized Tancred as King of Sicily and vowed to keep the peace between all three of their kingdoms.

- Richard officially proclaimed his nephew Arthur of Brittany as his heir presumptive, and Tancred promised to marry one of his daughters to Arthur when he came of age (Arthur was four years old at the time).

Excalibur London Film Museum via Wikipedia

After signing the treaty, Richard and Philip finally left Sicily for the Holy Land. It is rumored that before he left, Richard gave Tancred a sword he claimed was Excalibur in order to secure their friendship.”

Yes, you read this correctly. King Richard the Lionhearted gave my many-times great grandfather Excalibur, the legendary sword of mythical King Arthur.

I doubt Richard the Lionhearted would really give away a sword that was supposed to prove his lineage back to the Pendragon if he actually believed it was truly Arthur’s. However, it is a documented fact that he did indeed give this sword of historical significance to Tancred.

I suspect that Tancred believed it was the true sword of King Arthur as much as I do, but in the interest of peace, he most likely smiled and thanked his departing guest. Whatever he did with it, it was never seen again. When he came to reclaim his island after Tancred’s death, Henry IV, king of the Holy Roman Empire, pillaged Tancred’s treasury and the sword was not there.

But what, you ask, does my illegitimate many-times-great grandfather’s possession of the possibly faux Excalibur have to do with communication?

Tancred and Richard both had to be there in Sicily in person and had to communicate through messengers to arrange all this swapping of women and dowries and swords of dubious origin.

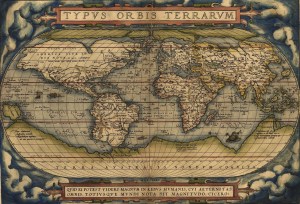

Good long-distance communication has always been seen as critical to good governing. Wars were won and lost based on the information those kings and generals received. During the Middle Ages, postal systems were invented, became corrupt, and fell into disuse all over Europe. This recurred at different times up through the eighteenth century.

In 1505, Emperor Maximilian I established one of the more stable postal systems, but it was not a thing the peasant class could avail themselves of. An illiterate peasant could hire a scribe, but then they would also have to scrape up more coins to get the note sent to its destination. It was better to pay a neighbor to carry the news to wherever it had to go.

There was a faster method of getting a letter home. Long before the Middle Ages and during them, homing pigeons were used to carry messages. Rock pigeons have the ability that taken far from their nest, they’re able to find their way home. This due to a particularly developed sense of orientation. Messages were then tied around the legs of the pigeon, which was freed and could reach its original nest.

There was a faster method of getting a letter home. Long before the Middle Ages and during them, homing pigeons were used to carry messages. Rock pigeons have the ability that taken far from their nest, they’re able to find their way home. This due to a particularly developed sense of orientation. Messages were then tied around the legs of the pigeon, which was freed and could reach its original nest.

This is of limited usefulness because pigeons will only go back to the one place that they have identified as their home. Pigeon mail can only work when the sender has a specific recipient in mind and has possession of that receiver’s pigeons.

So how did they do this? The sender had to hand-carry the pigeons with them. Once released, the pigeons would fly back home with the note. Correspondents could not send a pigeon anywhere but the one place the birds considered their home.

If you are an author writing in an era other than the modern times, be diligent and do the research before you write about things that are outside your personal experience. Readers may have knowledge that you don’t and they will definitely not be shy about letting you know where you’ve gone wrong.

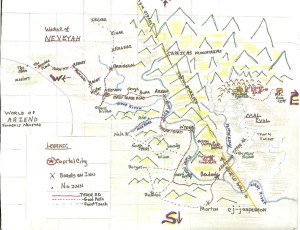

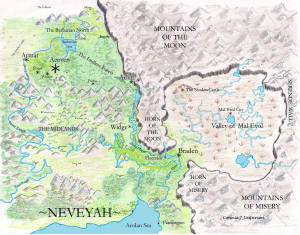

Much of my work is set in medieval environments, and so I can’t have my characters getting instantaneous information from afar without divine intervention. If my characters need to communicate over long distances, I have to consider the length of time it would take even a fast messenger to travel over roads we would consider impassable, but which were the medieval equivalent of I-5.

This kind of information is available via the internet. Researching my subject online is how I discovered that regular mail delivery is a relatively modern invention. Perusing Ancestry.com is how I discovered the medieval Norman/Sicilian roots of my mother’s family, the (Fitz)Rogers family.

Every now and then I find myself reading/listening to a mainstream bestseller, and enjoying it. Alexander Chee has written just such a novel, in The Queen of the Night.

Every now and then I find myself reading/listening to a mainstream bestseller, and enjoying it. Alexander Chee has written just such a novel, in The Queen of the Night.