I can’t deny my sincere love of all things sci-fi or fantasy. While I read in every genre, speculative fiction is my “comfort food.” I purchase both indie and traditionally published work and read them all.

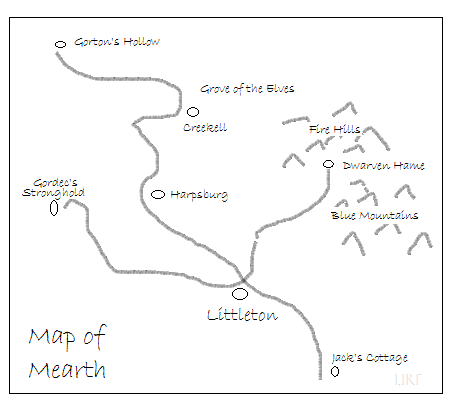

Two months ago, we began our series, Idea to Story. The previous nine installments are listed below, but throughout the series, we have built our two main characters. Val, (Valentine), is a lady knight and captain of the Royal Guard. The initial enemy, Kai Voss, is the court sorcerer. Both are regents for the sickly, underage king. Most of the other characters are in place.

Two months ago, we began our series, Idea to Story. The previous nine installments are listed below, but throughout the series, we have built our two main characters. Val, (Valentine), is a lady knight and captain of the Royal Guard. The initial enemy, Kai Voss, is the court sorcerer. Both are regents for the sickly, underage king. Most of the other characters are in place.

I must be honest—both sides of the publishing industry, indie and traditional, are guilty of publishing novels that aren’t well thought out. Thus, we are planning our novel so that we can avoid contradictions.

Inconsistencies in the science or magic system are usually only one aspect of haphazard plotting and world-building. When an author or publisher skimps on the revisions or ignores the beta reader’s concerns, they can be unaware of the contradictions built into the narrative. If they rush it to publication, the book fails the reader.

Magic must be treated the same way science is. It must be presented as a naturally occurring aspect of the world our characters inhabit.

Magic must be treated the same way science is. It must be presented as a naturally occurring aspect of the world our characters inhabit.

- Magic and the ability to wield it gives a character power.

- Science and superior technology also give our characters power.

Power and how we confer it is the layer of world-building where writers of science and writers of magic must follow the same rules.

Science is not magic, and it should not feel to a reader as if it were. It is logical, rooted in the realm of both factual and researchable theoretical physics. Science is limited by the boundaries of human knowledge and our ability to build technology.

However, an author’s imaginative exploration of theoretical physics makes the possibilities boundless.

In my opinion, magic should be like science. It should follow certain natural laws and have limits. Magic is believable when the ways it can be used are restricted and most sorcerers are constrained by the laws of nature to mastering only one or two kinds.

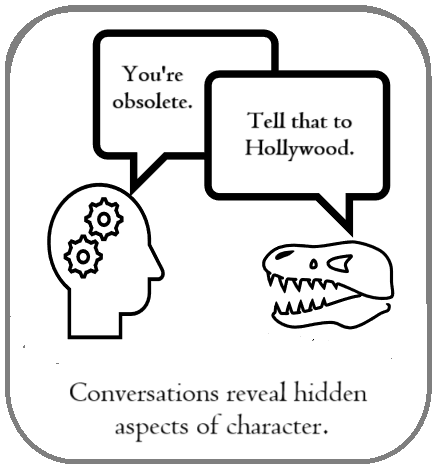

But why restrict your beloved main character’s abilities? The obvious answer is to allow your character to grow, to give them a true character arc. No one has all the skills in real life, no matter how good they are at their job. Limits create tension, and tension keeps the reader reading. When too many people are given superior powers, you make things too easy.

But why restrict your beloved main character’s abilities? The obvious answer is to allow your character to grow, to give them a true character arc. No one has all the skills in real life, no matter how good they are at their job. Limits create tension, and tension keeps the reader reading. When too many people are given superior powers, you make things too easy.

I have read many sci-fi and fantasy novels featuring characters with empathic gifts.

- In fantasy, it is portrayed as a form of magic.

- In science fiction, it’s portrayed as a mysterious property of the quantum universe that some people can access.

If an empathic gift has entered your narrative, ask yourself these questions: what sort of empathic gift does your character have? Are they good at emotion reading, mind reading, healing, or foresight?

If an empathic gift has entered your narrative, ask yourself these questions: what sort of empathic gift does your character have? Are they good at emotion reading, mind reading, healing, or foresight?

- How common or rare is this gift?

- How did they discover they had it?

- What can they do with it?

- What can they NOT do with it?

- Is there formal training for gifts like theirs?

- What happens to people who use their empathy to abuse others?

- Has society made laws regulating how empaths are trained and controlled?

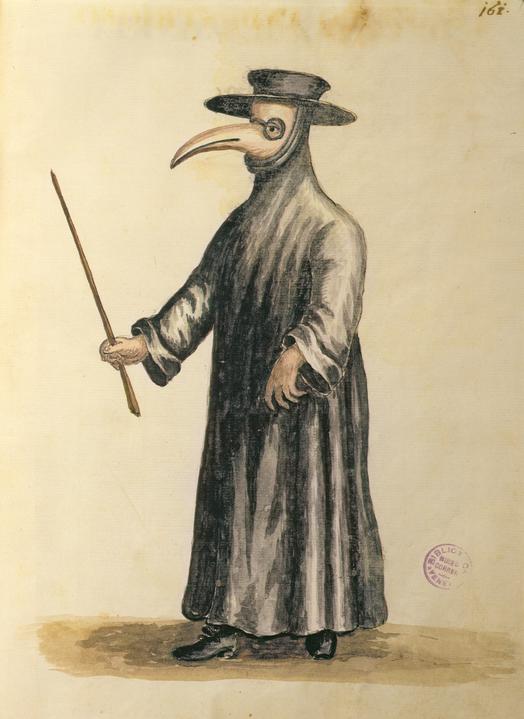

Are you writing a book that features magic? I have a few questions that you may want to consider:

- How do they learn to fully use their gifts? Apprenticeship? Trial and error? A formal school, ala Harry Potter?

- Are there some conditions under which the magic will not work? Is the damage magic can do as a weapon, or is the healing it can perform somehow limited?

- Does the mage or healer pay a physical/emotional price for using or abusing magic? Is the learning curve steep and sometimes lethal?

When you answer the above questions, you create the Science of Magic.

So, what about superpowers?

Superpowers are both science and something that may seem like magic, but they are not. Think Spiderman. His abilities are conferred on him by a scientific experiment that goes wrong.

Like science and magic, superpowers are believable when they are limited in what they can do.

If you haven’t considered the challenges your characters must overcome when wielding magic or weapons technology, now is a good time to do it.

- How is their self-confidence affected by this inability?

- Do the companions face learning curves, too?

- How can they remedy this situation?

These limits are the roadblocks to success. Overcoming them offers opportunities for action and growth.

These limits are the roadblocks to success. Overcoming them offers opportunities for action and growth.

In the story we have been plotting for the last nine weeks, Kai is the court sorcerer. At their father’s behest, he was trained in the art of sorcery by his half-brother. Donovan is slick, always playing the long game. He made sure that Kai does not have full knowledge of the craft, although, at the outset, Kai is unaware of this treachery. When Donovan makes his move, Kai is utterly defeated and ends up in the dungeon.

Val springs him from the dungeon when she escapes, but then what? How can we resolve Kai’s knowledge gap and give him an edge his brother can’t detect? We need to find him another teacher or two.

Valentine’s grandmother is an herb woman blessed with some empathic abilities. She has knowledge Kai could benefit from. She also has friends who are practitioners of a way of magic that is considered beneath the formal school Donovan and Kai were trained in. If Kai can stop being a spoiled rich boy, he can learn what he needs to know.

Val has no magic but has knowledge of available military technology and ideas for how it can be used in unexpected ways. All she has to do is stop looking down her nose at Kai and work with him.

Her grandmother will resolve that situation with a sharp dose of reality for both our protagonists.

The limits of their magic and technology force Kai and Val to be creative. If they are going to rescue the boy king from Donovan’s clutches, they need to use that creativity. Our characters must become more than they believe they are.

Whether your story is set in a medieval castle or a space station, limiting the personal power of the protagonist creates tension, raises the stakes, and makes the story more believable.

Next up – Genre, Themes, and the Expected Tropes of our story

Previous in this series:

Idea to story part 2: thinking out loud #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 3: plotting out loud #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 4 – the roles of side characters #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 5 – plotting treason #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 6 – Plotting the End #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 7 – Building the world #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 8 – world-building and society #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 9 – technology and world-building #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

![Nicolaes Maes, The Account Keeper, ca. 1656, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/nicolaes_maes_-_the_account_keeper.jpg?w=500)

Artist: Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

Artist: Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)