This last week has been extremely busy. I was able to bring my husband home from the rehab facility, and that was a wonderful thing. However, the transition has not been painless. He is mostly wheelchair-bound and can’t reliably communicate his needs. Fortunately, I have caregivers coming in every morning and evening to help with the rougher parts of his day.

Prose, and finding the right words to convey more than merely a recounting of fictional events is on my mind. Unfortunately, I was so busy that time got away from me, and I didn’t have time to write a proper post on that subject.

So, I am revisiting a post from 2020. The evolution of language is, I believe, a natural thing. And now, without further discussion, here is my post:

I think of poetry and language as coming into existence as conjoined twins. I can remember anything I can set to a rhyme or make into a song.

I think of poetry and language as coming into existence as conjoined twins. I can remember anything I can set to a rhyme or make into a song.

Yet, much of the time, modern songs and poetry don’t rhyme. Even so, they have tempo and rhythm.

If it doesn’t rhyme, what makes poetry “poetic?” And where does it fit into modern narrative prose?

Poetry is a primal form of communication in the human species, the literary invention that emerged as soon as we had words. It presents thoughts and feelings as abstractions and allusions rather than the concrete.

Poets select words for the impact they deliver. An entire story must be conveyed using the least number of words possible. For that reason, choices are made for symbolism, power, and syllabic cadence, even if there is no rhyme involved.

Narrative prose is broader, looser, more all-encompassing, with no limit on how long it takes for the story to unfold.

Modern humans deliver highly detailed concepts and ideas with packets of noise formed into individual words. We learn the meanings of these sound-packets as infants. By stringing these meaningful sound-packets together, we can share information with others of our species.

I suspect using rhyme as a mnemonic is fundamental to human nature. Research with modern primates in the wild proves that, while we were still in Africa before the great diaspora, humans developed complex languages within our tribal communities.

By observing primates in the wild, we see that our earliest ancestors had the ability to describe the wider world to their children. With that, we could teach them skills and the best ways to acquire food.

We understood and were able to see the motives of another person.

We developed compassion and burial rites.

Early humans relied on the cadence of repetition and rhyme. They could explain the how and why of a great flood or any other natural disaster, passing it forward across many generations.

The availability of food is central to the prosperity of all life, not just humans. Our ancestors saw the divine in every aspect of life, especially around the abundance or scarcity of food. They developed mythologies combining all of these concepts to explain the world around us and our place in it.

With the ability to pass on knowledge of toolmaking, we had leisure to contemplate the world. We discussed these things while eating and sharing food with each other.

We now know that other primates also deliver information by using sound-packets. Gorillas have been observed singing during their meals. Humans have always sung.

We now know that other primates also deliver information by using sound-packets. Gorillas have been observed singing during their meals. Humans have always sung.

Chimpanzees and Bonobos have been observed chatting during leisurely meals.

We humans love to sit around the table and chat.

The larynx and vocal cords of each primate species are formed differently, which affects how they communicate. They understand each other perfectly, but because they are so different from us, our human ears can’t differentiate the meanings of the individual sound-packets that make up their calls.

To us, their communications are just mindless screeching, and so we have always assumed they must not be self-aware.

I suspect that in years to come we will find that we have been wrong. We may be the only species we reliably converse with, but we are not the only self-aware species who communicate through vocalizations.

For many humans, dogs and cats are their beloved family members, self-aware people who love and accept them like no one else does.

This brings me to another point – if we can’t figure out and understand the languages of the other intelligent creatures in this world, i.e., Elephants, Cetaceans, and other Primates, then how can we ever expect to communicate with an alien extraterrestrial being?

And if we can’t recognize, value, and protect the individual self-awareness and personhood of beings like Elephants, Cetaceans, and other Primates, how will we recognize an extraterrestrial life-form? How will we behave toward them? After all, to us, these fellow creatures of earth have been nothing but resources for us to exploit.

Like modern Great Apes, proto humans used rhyme and cadence to memorize and pass on ideas as abstract as legends or sagas to their children and to others they might meet in friendly circumstances. By handing down those stories through the generations, we learned lessons from the mistakes and heroism of our ancestors.

Rhyme and cadence were fundamental to our ability to make tools out of stone and bone. The capacity to learn, remember, and reliably pass on knowledge was why the three human genomes we call Homo Sapiens, Neanderthal, and Denisovan could master fire. This is why they could develop the tools that made them the apex predators we became. We could reliably feed our young, rear them to adulthood, and still have time to create art on the walls of caves.

Every tribe, every culture that ever arose in our world, had a tradition of passing down stories and legends using rhyme and meter. Rhyme, combined with repetition and rhythmic simplicity, enabled us to remember and pass on our histories and knowledge to our children.

In times gone by, writers used words for their beauty, employing them the way they decorated their homes. Authors labored over their sentences, ensuring each word was placed in such a way as to be artistic as well as impactful.

In times gone by, writers used words for their beauty, employing them the way they decorated their homes. Authors labored over their sentences, ensuring each word was placed in such a way as to be artistic as well as impactful.

In writing poetry, we are forced to think on an abstract level. We must choose words based on their power. The emotions these words evoke, and the way they show the environment around us is why I gravitate to narratives written by authors who are also poets—the creative use of words elevates what could be mundane to a higher level of expression. When it’s done subtly, the reader doesn’t consciously notice poetic derivations in prose, but they are moved by them.

We have no need to memorize our cultural knowledge anymore, just as we no longer need the ability to accurately tally long strings of numbers in our heads. Readers seek out books with straightforward prose and few descriptors. Words for the sake of words is no longer desirable to the modern reader.

Modern poetry has evolved too. The love of poetry continues, and new generations seek out the poems of the past while creating powerful poetry of their own.

Modern authors, such as Patrick Rothfuss in his novel, The Name of the Wind craft narratives packed with powerful, evocative prose. We eagerly read their work because it is both straightforward and poetic. Most readers are unaware that they are drawn to the subtle poetry of his work as much as to the story that unfolds within the narrative.

I write poetry, some that follow traditional rhyming, and much that does not. Regardless of the structure, the cadence of syllables and the words I choose are recognizably mine. The emotions they evoke and the way they portray the environment I imagine is what lends my voice to my work.

Authors like me who read and sometimes write speculative fiction can enjoy our modern stripped-down narratives, guilt free.

That said, we who love the rhythm and cadence of words can still appreciate beauty combined with impact when it comes to our prose. And, if you love dark, heroic speculative fiction and haven’t yet read The Name of the Wind, by Patrick Rothfuss, I highly recommend it.

Credits and Attributions:

Admiring the Galaxy |CCA 4.0 ESO/A. Fitzsimmons

Artist: Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

Artist: Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

Most of my novels and short stories begin life as exchanges of dialogue between two characters. Their conversations shed light on what each character’s role in the story might be.

Most of my novels and short stories begin life as exchanges of dialogue between two characters. Their conversations shed light on what each character’s role in the story might be. Action: She comes down for coffee. He holds a notebook, gathers pens, and stands.

Action: She comes down for coffee. He holds a notebook, gathers pens, and stands.

Artist: Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/1629–1682)

Artist: Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/1629–1682) So why am I always pressing you to use proper punctuation? Authors must know the rules to break them with style. Readers expect words to flow in a certain way. If you break a grammatical rule, be consistent about it.

So why am I always pressing you to use proper punctuation? Authors must know the rules to break them with style. Readers expect words to flow in a certain way. If you break a grammatical rule, be consistent about it. Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Alexander Chee, and George Saunders all have unique voices in their writing. Each of these writers has written highly acclaimed work. Their prose is magnificent. When you have fallen in love with an author’s work, you will recognize their voice.

Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Alexander Chee, and George Saunders all have unique voices in their writing. Each of these writers has written highly acclaimed work. Their prose is magnificent. When you have fallen in love with an author’s work, you will recognize their voice. Tad Williams

Tad Williams Craft your work to make it say what you intend in the way you want it said, but be prepared to defend your choices if you deviate too widely from the expected.

Craft your work to make it say what you intend in the way you want it said, but be prepared to defend your choices if you deviate too widely from the expected.

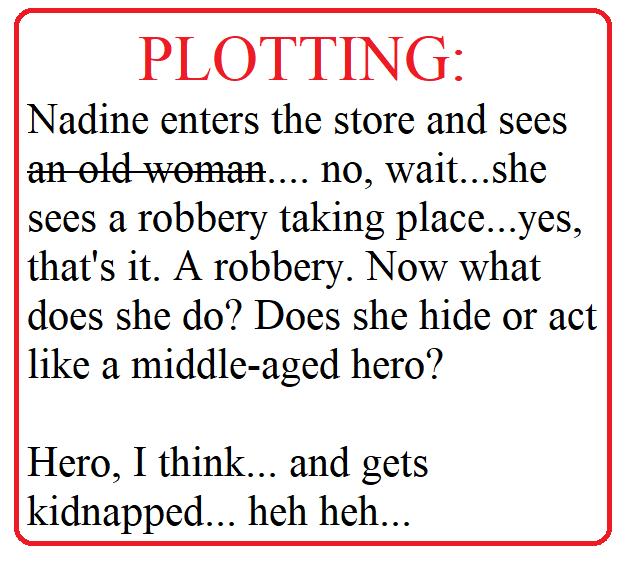

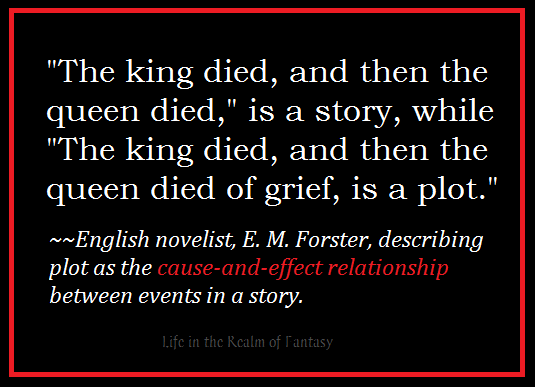

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning.

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning. I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending.

I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending. Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals.

Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals. Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

Artist: Georges Seurat (1859–1891)

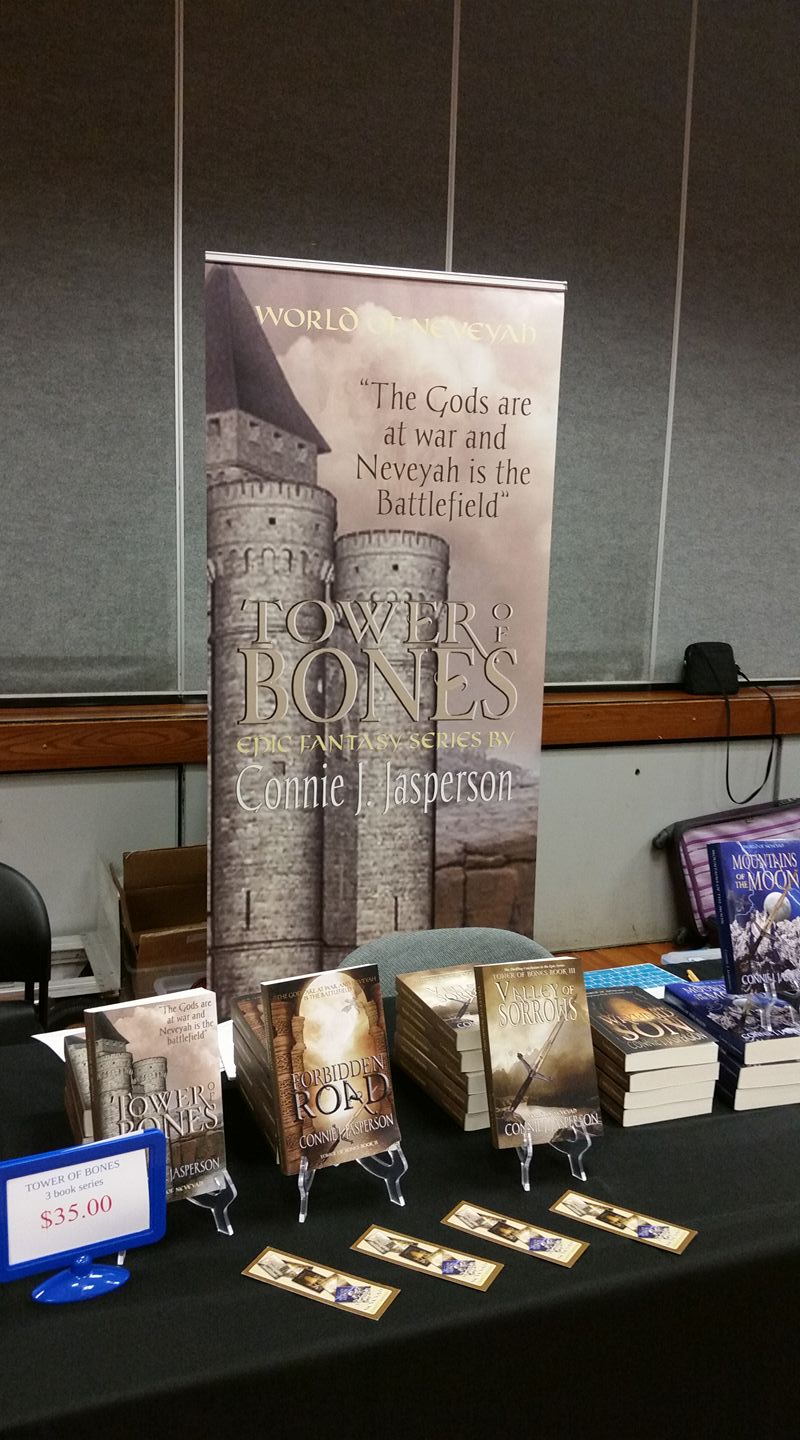

Artist: Georges Seurat (1859–1891) Nowadays, I am rarely able to do in-person events due to family constraints, but I used to do four events a year. However, I have some tips to help ease the path for you.

Nowadays, I am rarely able to do in-person events due to family constraints, but I used to do four events a year. However, I have some tips to help ease the path for you. The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like

The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like  Investing in some large promotional graphics, such as a retractable banner, is a good idea. A large banner is a great visual to put behind your chair. A second banner for the front of the table looks professional but requires some fiddling with pins.

Investing in some large promotional graphics, such as a retractable banner, is a good idea. A large banner is a great visual to put behind your chair. A second banner for the front of the table looks professional but requires some fiddling with pins. Make your display attractive, but I suggest you keep it simple. People will be able to see what you are selling, and the more fiddly things you add to your display, the longer setup and teardown will take. The shows and conferences I have attended offered plenty of time for this, but I’ve heard that some of the big-name conventions require you to be in or out in two hours or less.

Make your display attractive, but I suggest you keep it simple. People will be able to see what you are selling, and the more fiddly things you add to your display, the longer setup and teardown will take. The shows and conferences I have attended offered plenty of time for this, but I’ve heard that some of the big-name conventions require you to be in or out in two hours or less.

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) I think of poetry and language as coming into existence as conjoined twins. I can remember anything I can set to a rhyme or make into a song.

I think of poetry and language as coming into existence as conjoined twins. I can remember anything I can set to a rhyme or make into a song.