We’re well into NaNoWriMo, and writing is going well so far. I’m on track, and the words are flowing well. At our Saturday write-in, one of my fellow writers asked me how I introduce food into a narrative. As you might imagine, I have an opinion about that: I see food as set dressing, a part of world-building.

Food scenes serve as transitions between events. The act of dining occurs, but the conversations are the point of that scene. This is an opportunity to rest and regroup.

Food scenes serve as transitions between events. The act of dining occurs, but the conversations are the point of that scene. This is an opportunity to rest and regroup.

I write books set in fantasy environments, but you create a world no matter what genre you write in. As that world grows on paper, so does the culture. An aspect of worldbuilding involves including the casual mention of appropriate food for your ecology and level of technology.

I feel it’s best to concentrate on the conversations when writing about meals. The food should be part of the scenery. The conversations around food are where new information can be exchanged, things we need to know to move the story forward.

I’ve read many unforgettable fantasy books. One that shall go unnamed stands out, but not for a good reason. The author gave each kind of fruit, bird, or herd beast a different, usually unpronounceable, name in the language of her fantasy culture. She must have spent hours devising that hot mess of fantasy foods.

I’ve read many unforgettable fantasy books. One that shall go unnamed stands out, but not for a good reason. The author gave each kind of fruit, bird, or herd beast a different, usually unpronounceable, name in the language of her fantasy culture. She must have spent hours devising that hot mess of fantasy foods.

The characters were great and engaging, and the plot was engrossing. But the information about each and every kind of plant or vegetable was inserted into the narrative in long info dumps that ruined what could have been a great book for me.

As a reader, I think Tolkien got the food right when he created the Hobbit and the world of Middle Earth. He served common everyday food that his target audience was familiar with.

Food is an essential component of a culture but should be only briefly mentioned. Whether commonplace or exotic, it should be similar enough to known earthly foods to create an atmosphere a reader can easily visualize.

As many of you know, I have been vegan since 2012. However, during the 1980s, my second ex-husband and I raised sheep as part of a family cooperative.

I could write a book about those five years, but no one would believe it—fantasy is easier to make sense of.

I grew up fishing with my father and have a first-person understanding of putting meat, fish, or fowl on the table when a supermarket is not an option.

That experience taught me many things. Meat, fish, and fowl won’t be served daily in the average person’s home if they must catch, kill, and prepare it for themselves.

Village Scene with Well, Josse de Momper and Jan Brueghel II PD|100 via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s a lot of work to raise an animal. Hunting is also labor intensive. Then you have a lot of messy, smelly work to prepare it for cooking.

Travelers often streamline this process by skinning game birds rather than plucking them. The feathers come off with the skin – the whole point of hunting for dinner is to get it roasting as quickly as possible.

Why not raise animals and eat them? In the Middle Ages, pigs were raised solely for meat. The wool a sheep could produce in its lifetime was of far more value than the meat you might get by slaughtering it. For that reason, lamb was rarely served. The only sheep that made it to the table were usually rams culled from the herd.

Chickens were no different because you lose the many meals her eggs would have provided once a chicken is dead. Young roosters were culled before they got to the contentious stage and were usually the featured meat in the Sunday stew. Only one rooster was kept for breeding purposes. If he was too ill-tempered, he went into the stew pot, and a young rooster with better manners took his place.

Cattle and goats were also more valuable alive. Cows were integral to a family’s wealth as they were milk producers and sometimes worked as draft animals. Only one bull would be kept intact in a small herd for breeding purposes. The others would be neutered, made into oxen and draft animals that pulled plows, pulled wagons, fertilized the fields with their manure, and did all the work that heavy farm machinery does today.

In medieval times, it was a felony for commoners in Britain to hunt for game on many estates. Poachers were considered thieves and faced harsh penalties, horrific by our standards, if they were caught.

Cucumbers waiting to be pickles © 2013 cjjasp

However, most people were allowed to fish as long as they didn’t take salmon, so hutch-raised rabbits, fish, or salted pork were on the menu more often than fowl, sheep, or cattle. Eels and frogs were abundant and were a menu staple in the average peasant’s home. Anything one could raise in a garden was carefully harvested and pickled or dried. Berries were dried or made into jams and wines, as were tree fruits. Fish were dried and smoked or salted, and even pickled. These preserves were critical to surviving winters.

Common vegetables in medieval European gardens were leeks, garlic, onions, turnips, rutabagas, cabbages, carrots, peas, beans, cauliflower, squashes, gourds, melons, parsnips, aubergines (eggplants)—the list goes on and on. But what about fruits?

Wikipedia says:

Fruit was popular and could be served fresh, dried, or preserved, and was a common ingredient in many cooked dishes. Since sugar and honey were both expensive, it was common to include many types of fruit in recipes that called for sweeteners of some sort. The fruits of choice in the south were lemons, citrons, bitter oranges (the sweet type was not introduced until several hundred years later), pomegranates, quinces, and grapes. Farther north, apples, pears, plums, and wild strawberries were more common. Figs and dates were eaten all over Europe but remained expensive imports in the north. [1]

Pies of all kinds were the fast food of the era, often sold by vendors on the street or in bakeries.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder – Peasant Wedding (1526/1530–1569) via Wikimedia Commons

Wheat was rare and expensive. For that reason, the grains most often found in a European peasant’s home were barley, oats, and most importantly, rye. In the Americas, maize (corn)was the staple grain that provided flour for bread and was an essential ingredient in cooking.

Mostly, my characters eat fish, vegetables, grains, fruits, and nuts. The primary sources of protein are eggs, cheese, and fish. Herbal teas, ale, ciders, and mead are staples of the commoner’s diet. This is because drinking fresh, unboiled water can be unhealthy if your tale is set in a low-tech world. Medieval beers and ales were lower in alcohol but higher in nutrition than today’s brews. Ale or lager might be served at every meal, even to children.

In my current work in progress, my people have a melding of familiar European and New World ingredients for their diet and do a lot of foraging. Fish, maize, and potatoes are essential staples, as are beans and wild greens. For a good list of what this diet might entail, visit this link: Indigenous cuisine of the Americas. You will be amazed at the variety of everyday foods that originated in the Americas.

In my current work in progress, my people have a melding of familiar European and New World ingredients for their diet and do a lot of foraging. Fish, maize, and potatoes are essential staples, as are beans and wild greens. For a good list of what this diet might entail, visit this link: Indigenous cuisine of the Americas. You will be amazed at the variety of everyday foods that originated in the Americas.

Knowing what to feed your people keeps you from introducing jarring components into your narrative. But don’t make it the center of the scene unless your plot demands it. One of my favorite series does just that: Recipes for Love and Murder: A Tannie Maria Mystery (Tannie Maria Mystery, 1)

CREDITS AND ATTRIBUTIONS:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Medieval cuisine,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Medieval_cuisine&oldid=896980025 (accessed Nov 4, 2023).

Apples and pickles courtesy of the author’s own kitchen garden.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder – Peasant Wedding (1526/1530–1569) PD|100 via Wikimedia Commons.

Village Scene with Well, Josse de Momper and Jan Brueghel II PD|100 via Wikimedia Commons.

Title: After the Rain Gloucester

Title: After the Rain Gloucester On Monday, I had to drive to Seattle to take the hubby for a consult with a neurosurgeon. Getting to the doctor was fine. It was a matter of spending one hour sitting in traffic trying to leave Olympia and another hour of actually rolling forward once we made it past the Nisqually River. I had planned ahead for that, so we were on time. The upshot is no back surgery for him unless there is no other option, as Parkinson’s patients do very poorly after surgeries.

On Monday, I had to drive to Seattle to take the hubby for a consult with a neurosurgeon. Getting to the doctor was fine. It was a matter of spending one hour sitting in traffic trying to leave Olympia and another hour of actually rolling forward once we made it past the Nisqually River. I had planned ahead for that, so we were on time. The upshot is no back surgery for him unless there is no other option, as Parkinson’s patients do very poorly after surgeries. So, what am I writing today? I’m working on the second half of a novel I began writing seven years ago, so all the world-building and character creation has happened. The plot for this half is evolving. I know the ending, and over the next thirty days, my characters will take me from this high point in the middle, through several hurdles yet to be determined, to that final victory.

So, what am I writing today? I’m working on the second half of a novel I began writing seven years ago, so all the world-building and character creation has happened. The plot for this half is evolving. I know the ending, and over the next thirty days, my characters will take me from this high point in the middle, through several hurdles yet to be determined, to that final victory. I’m settling into the new office. In my old house, my ramshackle desk was in the Room of Shame, a jumbled mess of a storeroom. My new desk is not duct taped together and has the right amount of storage for what I need.

I’m settling into the new office. In my old house, my ramshackle desk was in the Room of Shame, a jumbled mess of a storeroom. My new desk is not duct taped together and has the right amount of storage for what I need. Today, the office/guestroom walls are barren, but I hope to have all the family pictures hung by the end of this week. The hide-a-bed sofa and side chair make a pleasant conversation area or guest room, whichever is needed. All I lack is my new desk chair, which is on its way here from Norway. (Yes, I splurged on a Stressless desk chair since I spend most of my time sitting in front of my computer.) It should be here in a week or two, and I can hardly wait as my current desk chair loses its appeal after an hour or so.

Today, the office/guestroom walls are barren, but I hope to have all the family pictures hung by the end of this week. The hide-a-bed sofa and side chair make a pleasant conversation area or guest room, whichever is needed. All I lack is my new desk chair, which is on its way here from Norway. (Yes, I splurged on a Stressless desk chair since I spend most of my time sitting in front of my computer.) It should be here in a week or two, and I can hardly wait as my current desk chair loses its appeal after an hour or so. What are some of my planned treats? Cranberry and walnut shortbread, for one thing. Shortbread is so easy and affordable to make that it always surprises me when people don’t. I have veganized all of my old traditional recipes, so everyone can sneak a treat now and then.

What are some of my planned treats? Cranberry and walnut shortbread, for one thing. Shortbread is so easy and affordable to make that it always surprises me when people don’t. I have veganized all of my old traditional recipes, so everyone can sneak a treat now and then. Getting those ideas out of your head now is what is important. The bloopers and grammar hiccups can all be ironed out in the second draft.

Getting those ideas out of your head now is what is important. The bloopers and grammar hiccups can all be ironed out in the second draft. Yes, we do need to show moods, and some physical description is necessary. Lips stretch into smiles, and eyebrows draw together. Still, they are not autonomous and don’t operate independently of the character’s emotional state. The musculature of the face is only part of the signals that reveal the character’s interior emotions.

Yes, we do need to show moods, and some physical description is necessary. Lips stretch into smiles, and eyebrows draw together. Still, they are not autonomous and don’t operate independently of the character’s emotional state. The musculature of the face is only part of the signals that reveal the character’s interior emotions. Bad advice is good advice taken to an extreme. But all writing advice has roots in truth. So, when it comes to making revisions, consider these suggestions:

Bad advice is good advice taken to an extreme. But all writing advice has roots in truth. So, when it comes to making revisions, consider these suggestions: I recommend investing in a grammar book, depending on whether you use American or UK English. These books will answer your questions, and you won’t be in doubt about how to use the standard punctuation readers expect to see.

I recommend investing in a grammar book, depending on whether you use American or UK English. These books will answer your questions, and you won’t be in doubt about how to use the standard punctuation readers expect to see. I recommend checking out the NaNoWriMo Store, which offers several books to help you get started. The books available there have good advice for beginners, whether you participate in November’s writing rumble or want to write at your own pace.

I recommend checking out the NaNoWriMo Store, which offers several books to help you get started. The books available there have good advice for beginners, whether you participate in November’s writing rumble or want to write at your own pace. I study the craft of writing because I love it, and I apply the proverbs and rules of advice gently. Whether my work is good or bad—I don’t know. But I write the stories I want to read, so I am writing for a niche audience of one: me.

I study the craft of writing because I love it, and I apply the proverbs and rules of advice gently. Whether my work is good or bad—I don’t know. But I write the stories I want to read, so I am writing for a niche audience of one: me.

Magic or the supernatural are core plot elements in most of my work. I see them as part of the world, the way the Alps were a core plot element in the story of the

Magic or the supernatural are core plot elements in most of my work. I see them as part of the world, the way the Alps were a core plot element in the story of the  Hannibal paid a heavy price for bringing his superweapons (elephants) to the battle. The ability to use magic should come at some cost, either physical or emotional. Or it should require coins or theft to acquire magic artifacts.

Hannibal paid a heavy price for bringing his superweapons (elephants) to the battle. The ability to use magic should come at some cost, either physical or emotional. Or it should require coins or theft to acquire magic artifacts.  It’s fair to write stories where magic is learned through spells if one has an inherent gift, and it’s also fair to require a wand. That is how magic was always done in traditional fairy tales and J.K. Rowling took those worn-out tropes and made them new and wonderful.

It’s fair to write stories where magic is learned through spells if one has an inherent gift, and it’s also fair to require a wand. That is how magic was always done in traditional fairy tales and J.K. Rowling took those worn-out tropes and made them new and wonderful. I can suspend my disbelief when magic and supernatural abilities are only possible if certain conditions have been met. The best tales featuring characters with paranormal skills occur when the author creates a system that regulates what the characters can NOT do.

I can suspend my disbelief when magic and supernatural abilities are only possible if certain conditions have been met. The best tales featuring characters with paranormal skills occur when the author creates a system that regulates what the characters can NOT do. A crucial reason for establishing the science of magic and the paranormal before randomly casting spells or flinging fire is this: the use of these gifts impacts the wielder’s companions and influences the direction of the plot, creating tension.

A crucial reason for establishing the science of magic and the paranormal before randomly casting spells or flinging fire is this: the use of these gifts impacts the wielder’s companions and influences the direction of the plot, creating tension. or the paranormal in your NaNo novel, how can you take these common tropes in a new direction?

or the paranormal in your NaNo novel, how can you take these common tropes in a new direction? First, what sort of world is your real life set in? When you look out the window, what do you see? Close your eyes and picture the place where you are at this moment. With your eyes still closed, tell me what it’s like. If you can describe the world around you, you can create a world for your characters.

First, what sort of world is your real life set in? When you look out the window, what do you see? Close your eyes and picture the place where you are at this moment. With your eyes still closed, tell me what it’s like. If you can describe the world around you, you can create a world for your characters. What does the outdoor world look and smell like? Is it damp and earthy, or dry and dusty? Is there the odor of fallen leaves moldering in the gutters? Or have we wandered too near the chicken coop? (Eeew … get it off my shoe!) If an author can inject enough sight, sound, and scent into a fantasy or sci-fi setting, the world will feel solid when I read it.

What does the outdoor world look and smell like? Is it damp and earthy, or dry and dusty? Is there the odor of fallen leaves moldering in the gutters? Or have we wandered too near the chicken coop? (Eeew … get it off my shoe!) If an author can inject enough sight, sound, and scent into a fantasy or sci-fi setting, the world will feel solid when I read it.

What about transport? How do people and goods go from one place to another?

What about transport? How do people and goods go from one place to another? Names and directions might drift and change as you write your first draft. Also, if they’re invented words, consider writing them close to how they are pronounced.

Names and directions might drift and change as you write your first draft. Also, if they’re invented words, consider writing them close to how they are pronounced. Cider Pressing by George Henry Durrie 1855

Cider Pressing by George Henry Durrie 1855 When someone asks me what a book I wrote is about, my mind grinds to a halt as I try to decide what to say. I could give them the rundown of the plot, which is the arc of events the characters experience.

When someone asks me what a book I wrote is about, my mind grinds to a halt as I try to decide what to say. I could give them the rundown of the plot, which is the arc of events the characters experience. The story writes itself when I begin with a strong theme and solid characters. A 19th-century writer many have heard of but never read,

The story writes itself when I begin with a strong theme and solid characters. A 19th-century writer many have heard of but never read,  When

When Love is only one theme, yet it has so many facets. Other themes abound, large central concepts that build tension within the narrative.

Love is only one theme, yet it has so many facets. Other themes abound, large central concepts that build tension within the narrative. Sometimes, we can visualize a complex theme but can’t explain it. If we can’t explain it, how do we show it? Consider the theme of “grief.” It is a common theme that can play out against any backdrop, whether sci-fi or reality based, where humans interact on an emotional level.

Sometimes, we can visualize a complex theme but can’t explain it. If we can’t explain it, how do we show it? Consider the theme of “grief.” It is a common theme that can play out against any backdrop, whether sci-fi or reality based, where humans interact on an emotional level. Even if you don’t have an idea of what you want to write, it’s time to go out to

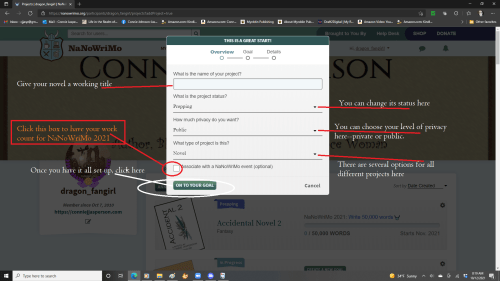

Even if you don’t have an idea of what you want to write, it’s time to go out to  Once there, create a profile. You don’t have to get fancy unless you are bored and feeling hypercreative.

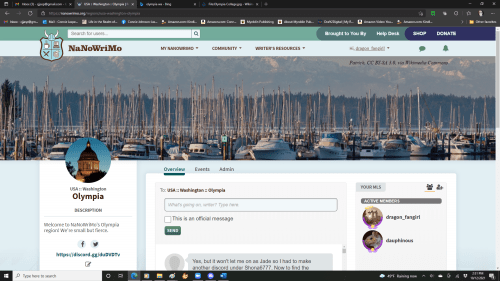

Once there, create a profile. You don’t have to get fancy unless you are bored and feeling hypercreative. You can play around with your personal page a little to get used to it. I use my NaNoWriMo avatar and name as my

You can play around with your personal page a little to get used to it. I use my NaNoWriMo avatar and name as my  Next, check out the community tabs. If you are in full screen, the tabs will be across the top. If you have the screen minimized, the button for the dropdown menu will be in the upper right corner and will look like the blue/green and black square to the right of this paragraph.

Next, check out the community tabs. If you are in full screen, the tabs will be across the top. If you have the screen minimized, the button for the dropdown menu will be in the upper right corner and will look like the blue/green and black square to the right of this paragraph. You may find the information you need in one of the many forums listed here.

You may find the information you need in one of the many forums listed here. Make a master file folder that is just for your writing. I write professionally, so my files are in a master file labeled Writing.

Make a master file folder that is just for your writing. I write professionally, so my files are in a master file labeled Writing. Give your document a label that is simple and descriptive. My NaNoWriMo manuscript will be labeled: Stowe_Bridge_NaNoWriMo_2023.

Give your document a label that is simple and descriptive. My NaNoWriMo manuscript will be labeled: Stowe_Bridge_NaNoWriMo_2023. This year we will have write-ins at the local library. The authors in our region will come together and write for two hours and support each other’s journey. We will also meet via the miracle of the internet, using Discord and Zoom. My co-ML and I are finalizing a schedule for November.

This year we will have write-ins at the local library. The authors in our region will come together and write for two hours and support each other’s journey. We will also meet via the miracle of the internet, using Discord and Zoom. My co-ML and I are finalizing a schedule for November.