Every year since 2010, I have participated in the annual challenge of writing a 50,000-word (or more) novel in November. I was a Municipal Liaison for the now defunct organization known as NaNoWriMo for twelve years, but dropped that gig when the folks at NaNo HQ got too full of themselves and lost the concepts the organization was founded on.

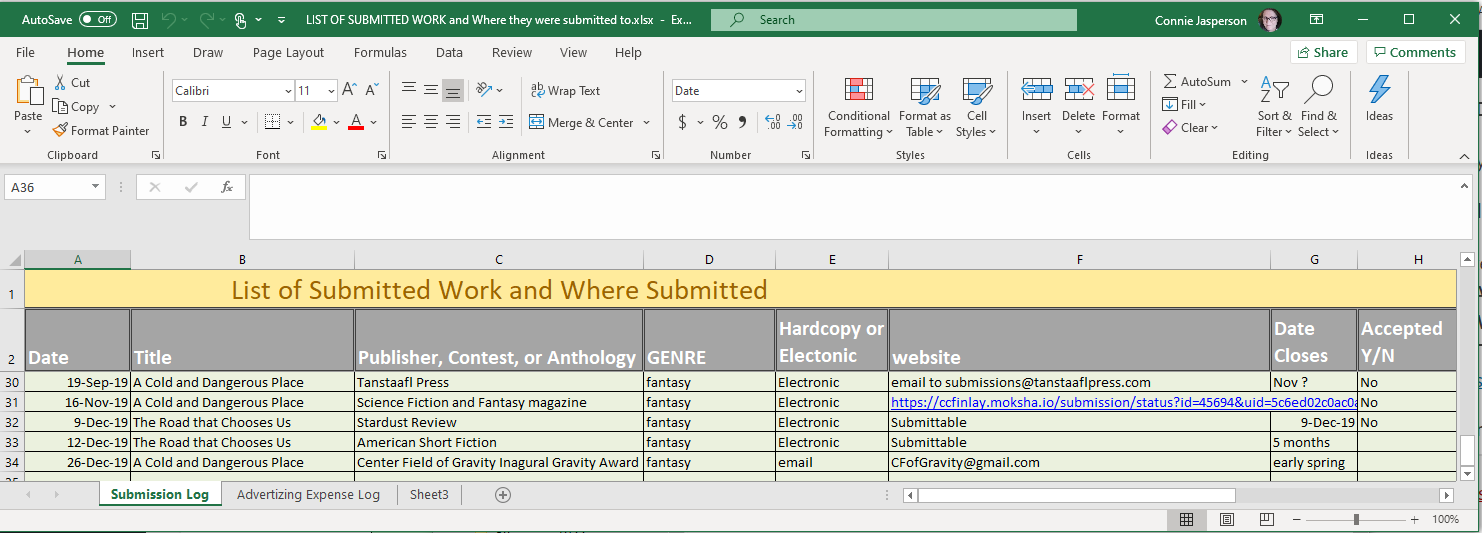

I still participated, just not on their website. Before I deleted my account, I took a screenshot of my header, as it showed my accumulated wordcount. During those years I wrote 1,409,399 words. Some years were easier than others, but I always came away with something useful.

Spending the time every day to get a certain number of new words written forces me to become disciplined. It requires me to ignore the inner editor, the little voice that slows my productivity down and squashes my creativity.

For those two reasons alone, I will most likely always be a November Writer.

I love the rush, the thrill of having laid down the first draft of something that could become better with time and revisions. I am competing against my lazy self and really making the effort to get a complete story arc on paper.

Have I ever mentioned how my family loves Indy Car and the Memorial Day Weekend extravaganza known as the Indy 500? Well, if I haven’t, it’s true.

I have had many favorite drivers, one of whom is Takuma Sato . You may ask how an Indy Car driver is relevant to my completion of November’s writing rumble, and I will tell you.

He approaches competing like a samurai warrior, and that is how I see making a daily wordcount goal in November. No Attack, No Chance: The Takuma Sato Story – THOR Industries

As Takuma Sato says, “No attack, no chance.”

To really commit to this and get your word count, you must become a Word Warrior. Even if you intend to wing it, a little advance prep is helpful.

Author Lee French, who was my co-ML and dear friend for all those years had a pep-talk she would give our writers, beginning in October, or Preptober as we veterans call it. She has kindly allowed me to quote her notes from 2020:

Pick any of these things you want to write about or with. Be as specific as possible for each thing. These things can come from a number of different categories, such as but not limited to:

-

Creatures – Dragons, demons, fae, vampires, elves, aliens, babies, wolves, mosquitoes, and so on. This includes anything nonhuman, and may refer to heroes, villains, or side characters of any importance.

-

Natural disasters – Tornadoes, earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis, melting polar ice caps, climate change effects, etc. This can mean a story that takes place during or after a disaster, or it can mean there’s a disaster looming and the goal is to prevent or mitigate it.

-

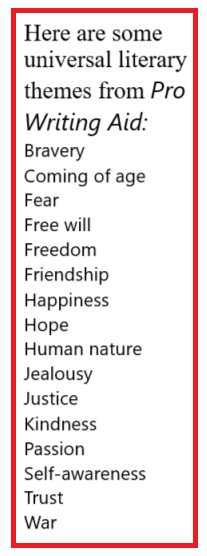

Themes – Love, death, survival, good vs. evil, prejudice, etc. Any theme will do. You can mix two, but should steer clear of more than that. If you’re not sure what constitutes a theme, google “story themes” for an array of options.

-

Relationships – Siblings, romance, platonic love, friendship, breaking up/divorce, etc.

-

Moods – Grim, utopian, dark, gritty, light, noble bright, comedic, etc.

-

Geography/type of area – Forest, mountains, urban, rural, caves, isolated, etc.

-

Phenomena – Magic, psychic powers, supernatural whatnot, miracles, and the like.

Once you have your list, take the time to think about it. Sit back, ruminate on each thing, and make some notes. This could take a few days, or as little as an afternoon. In 2020,

Lee’s five things looked like this:

Magic

- Secondary world fantasy.

- Other races exist.

- The MC uses magic in a lowkey way.

- Magic is not commonly used by ordinary people.

- There’s a squirrel.

Romance

- Cishet. Female MC, male Love Interest.

- The guy is different in some important way, like being nonhuman or following a religious path that’s frowned upon by most folk.

- The romance is a value-added bonus, not the plot.

Unexpected Ice Age

- Caused by magic.

- Affects the entire world.

- Makes survival challenging, especially for food and fuel.

- The cold is enough to kill fairly swiftly.

Good vs. Evil

- Bad guy is the leader of the city.

- No, wait. It’s two bad guys. They’re partners. Siblings?

- Good guy is in hiding.

- I think I need a secondary bad guy too, like a lieutenant.

Refuge City of Debris

- Jagged edges, abrupt changes in material, faded colors.

- The population is in the 2-5 thousand range.

- Surrounded by a wall or cliffs. Or both!

I have always loved the way her mind works.

For me, once I begin writing my new manuscript on November 1st, the hardest part is NOT SELF-EDITING!!! But overcoming that habit is crucial, and not just for wordcount. We need to get the ideas down while they are fresh, and any step backwards can stall the project.

Tips from me for a good November:

Tips from me for a good November:

Never delete and don’t self-edit as you go. Don’t waste time re-reading your work. You can do all that in December when you go back to look at what you have written.

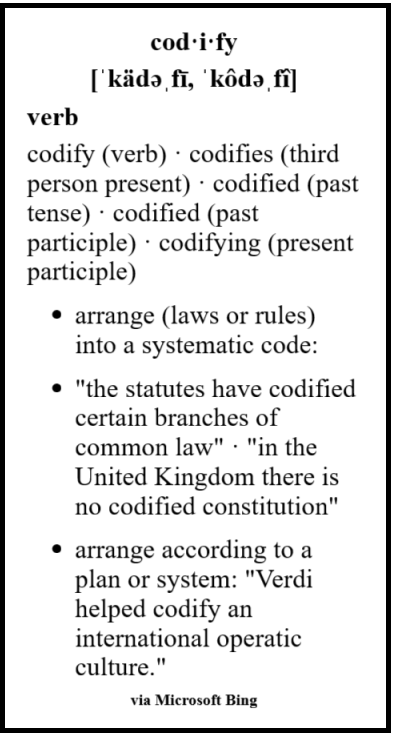

Make a list of all the names and words you invent as you go and update it each time you create a new one, so the spellings don’t evolve as the story does.

If wordcount is your goal, write 1670 words every day and you will have 50,000 words on November 30th.

This year for me, wordcount is important but not the entire enchilada. Writing the second book in my unfinished duology is the project that I intend to complete.

Here are some Resources to Bookmark in advance:

Three websites a beginner should go to if they want instant answers in plain English:

Most importantly, enjoy this experience of writing. There is no other reason to put yourself through this.

Credits and Attributions:

Special thanks to best-selling author of YA Fantasy and Sci-fi, Lee French, for allowing me to quote her work notes. She is an inspiration to me!