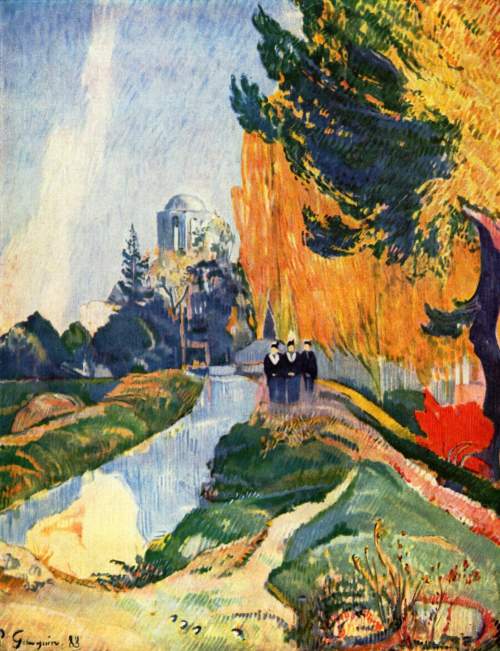

Twilight Confidences by Cecilia Beaux (1855–1942)

Twilight Confidences by Cecilia Beaux (1855–1942)

Date: 1888

Medium: oil on canvas

Dimensions: 23 1/2 x 28 inches, 59.7 x 71.1 cm

Inscriptions: Signed and dated: Cecilia Beaux

What I love about this painting:

This is one of my all-time favorite paintings. It is not merely a portrait of how two women looked on a summer’s day; it tells us a story. What that story is will be up to you, but in this very simple scene, two women beside the sea, Cecelia Beaux tells us many things.

First, we see brilliant world building in what Beaux has chosen to focus on: their expressive features, and the lonely stretch of beach where they can talk and not be overheard. The artist hasn’t cluttered it up with anything that is not necessary.

We know this was painted toward the end of Beaux’s time in France. The two women may be nurses, or they may be sisters of a religious order. Or, their dress and headwear may be a fashion of their local area, but I’m leaning toward young nurses.

There is an honesty, a real sense of intimacy depicted here. The feeling of sisterhood between the two women is conveyed across the years–they find it safe to confide in each other.

One holds an object with a personal meaning, perhaps a gift from a young man who is absent. She tells the other something about that object, a secret she feels she may be judged for. The other takes in what she has been told and accepts it for what it is.

About this painting via Wikimedia Commons:

Cecilia Beaux was a leading figure and portrait painter and one of the few distinguished and highly recognized women artists of her time in America. Her figures are frequently compared to Sargent’s, but her style relates also to other international leaders of late-19th Century portraiture, including Anders Zorn, Giuseppe Boldini, Carolus-Duran and William Merritt Chase. She was born and lived mostly in Philadelphia, traveling frequently to Europe, especially France from a young age, and exhibited widely in Paris, Philadelphia, New York and elsewhere. Her first acclaimed work, Les Derniers jours d’enfance, a mother and child composition, was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1887, and Beaux followed it there the next year, spending the summer of 1888 at the art colony at Concarneau in Brittany. Here she painted her remarkable Twilight Confidences of 1888, preceded by numerous studies, which are in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Lost for many years, this much admired canvas is Beaux’s first major exercise in plein-air painting, in which the figures and the seascape are artfully and exquisitely juxtaposed, and sunlight permeates the whole composition. [1]

Beaux was highly educated and had a brilliant career as one of the most respected portrait artists of her time. To read about this amazing woman’s life, go to Cecilia Beaux – Wikipedia.

Credits and Attributions:

IMAGE: Twilight Confidences, Cecilia Beaux, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

[1] Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Twilight Confidences by Cecilia Beaux.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Twilight_Confidences_by_Cecilia_Beaux.jpg&oldid=355146645 (accessed October 30, 2025).

Artist:

Artist: