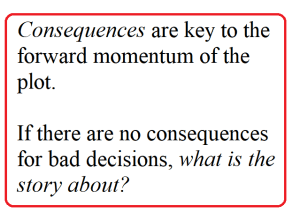

The word of the day is consequence.

The word of the day is consequence.

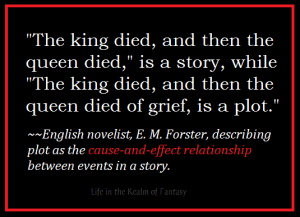

It’s a large word with many meanings and usages, but the one we’re concerned with today is its synonym, repercussion. Frankly, a story of actions without consequences is not much of a story.

Every choice our characters make should have repercussions, changing their lives for good or bad.

Once again, we will go to J.R.R. Tolkien and look at Bilbo’s choices and his path to becoming the eccentric eleventy-one-year-old hobbit who vanishes, literally, leaving everything he owned to his cousin, Frodo.

At the outset, Gandalf does the unforgivable. He scratches symbols into Bilbo’s pristine front door. To ruin a beautiful door like that? The fiend!

Worse, those symbols invite himself and twelve rough-looking strangers to be overnight guests in Bilbo’s home—and Bilbo is unaware of all this until the first guests appear at his door, expecting to be fed.

I don’t know about you, but I would be hard-pressed to scrape together the food to feed thirteen guests without a little advance notice.

In the morning, after the unexpected (and unwanted) guests leave him to his empty larder, he has two choices, to stay in the safety of Bag End, or hare off on a journey into the unknown. Bilbo chooses to run after the dwarves, and this is where the real story begins.

The Hobbit or There and Back Again is the story of how an honest and respectable middle-aged hobbit became a burglar. In the process, he became a hero who was forever changed by his experiences.

The consequences of his decision will alter his view of life forever afterward. Where he was once a staid country squire, having inherited a comfortable income and existence, Bilbo is now expected to steal an important treasure from a dragon.

The consequences of his decision will alter his view of life forever afterward. Where he was once a staid country squire, having inherited a comfortable income and existence, Bilbo is now expected to steal an important treasure from a dragon.

At the outset, the role of burglar doesn’t seem real. He is beset by problems, one of which is his general unfitness for the task. He’s always been well-fed, never had to exert himself much, and no one cares about his opinions. For someone who is used to being an important voice in the community, that disregard is painful.

Bilbo’s hidden sense of adventure emerges early when the company encounters a group of trolls. He is posing as a thief, so he is ordered to investigate a strange fire in the forest. Reluctantly, he agrees. Upon reaching the blaze, he observes that it is a cookfire for a group of trolls.

Bilbo has reached a fork in the path of life and must make a choice. He’s not stupid, and the smart thing would be to turn around at that point and warn the dwarves.

However, his ego feels the need to do something to prove his worth. “He was very much alarmed as well as disgusted; he wished himself a hundred miles away—yet somehow he could not go straight back to Thorin and Company empty-handed.” [1] Bilbo feels the need to impress the Dwarves, which drives him to make decisions he comes to regret.

In the process of nearly getting everyone eaten and having to be rescued by Gandalf, he discovers several historically important weapons. One of them is Sting, a blade that fits Bilbo perfectly as a sword. Gandalf and the dwarf Thorin also find their respective swords, Glamdring and Orcrist.

Bilbo’s blade does not acquire its name until later in the adventure, when Bilbo becomes lost in the forest of Mirkwood. He uses it to kill a giant spider, rescuing the Dwarves. These actions gain him some esteem from a few of the dwarves, the ones who aren’t as arrogant as Thorin.

Although Bilbo’s weapon is only a dagger for a human or dwarf, it is the perfect sword for a warrior the size of our hobbit. It turns out that, like the swords of Gandalf and Thorin, this dagger was forged by the elves of Gondolin in the First Age and possesses a magical property—it shines with a blue glow when orcs are close.

As the journey progresses, Bilbo develops a clearer perspective of his companions, caring about them despite their flaws. With each event, he becomes more introspective and aware, and his courageous side begins to emerge.

All along the way, every decision forces an action, which has consequences that force his character arc to grow. His experiences reshape him physically and emotionally. Bilbo no longer thinks like the naïve, slightly prejudiced member of the sedentary gentry that he was at the outset.

As the Dwarves continue to get into trouble, Bilbo makes plans for their rescue, and does so successfully, receiving only grudging gratitude from Thorin.

As the Dwarves continue to get into trouble, Bilbo makes plans for their rescue, and does so successfully, receiving only grudging gratitude from Thorin.

Bilbo is now a warrior, strong and capable of defending his friends from whatever they have dropped themselves into. However, if you asked him, he would say he was just an ordinary person.

Action and its consequences force our characters to grow emotionally. It changes their worldview. Sometimes the decisions our characters make as we are writing them surprise us. But if those decisions make the story too easy, they should be discarded.

We, as their creator, must take over, cut or rewrite those scenes, and force the story back on track.

After all, consequences make the story interesting.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Quote from The Hobbit, or There and Back Again, by J.R.R. Tolkien, published 1937 by George Allen & Unwin, Ltd.

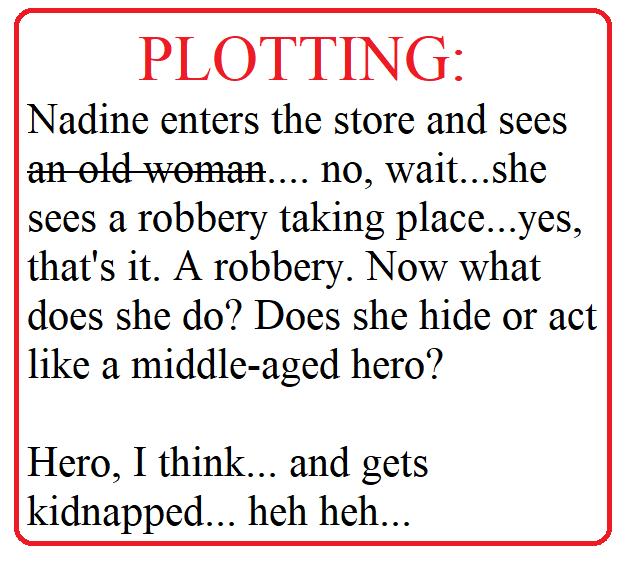

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning.

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning. I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending.

I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending. Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals.

Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals. Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

![Herbert Gustave Schmalz [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/imogen_-_herbert_gustave_schmalz.jpg?w=240)