A friend of mine recently said, “I did what some gurus suggested for NaNoWriMo and planned out my book. All the joy is off the idea now, and I want to do something different.” This is not an uncommon occurrence. For some people, planning the outline makes them feel they have already written the story and they lose their enthusiasm.

A friend of mine recently said, “I did what some gurus suggested for NaNoWriMo and planned out my book. All the joy is off the idea now, and I want to do something different.” This is not an uncommon occurrence. For some people, planning the outline makes them feel they have already written the story and they lose their enthusiasm.

I am a plotter, but I am also a pantser. A great article on this subject can be found at The Write Practice.

Quote: Simply put, a plotter is someone who plans out their novel before they write it. A pantser is someone who, “flies by the seat of their pants,” meaning they don’t plan out anything or plan very little.

Planning what events your protagonist will face is called plotting, and I make an outline for that.

“Pantsing it,” or writing using stream-of consciousness can produce some amazing work. That works well when we’re inspired, as ideas seem to flow from us. But for me, that sort of creativity is short-lived, unless I have a brief outline to follow, a road map of some sort.

Participating in NaNoWriMo has really helped me grow in the ability to write on a stream-of-consciousness level, but that only works for so long before I need a reminder of what my story was about in the beginning. My storyboard gets me back on track without making me feel like the creativity is already done.

One NaNoWriMo joke-solution often bandied about at write-ins is, “When you’re stuck, it’s time for someone to die.” Sadly, assassinating beloved characters whenever we run out of ideas is not a feasible option because we will soon run out of characters.

As devotees of Game of Thrones will agree, readers (or TV viewers) get to know characters and bond with them. When cherished characters are too regularly killed off, the story loses good people, and we must introduce new characters to fill the void. The reader may decide not to waste his time getting invested in a new character, feeling that you will only break their heart again.

The death of a character should be reserved to create a pivotal event that alters the lives of every member of the cast and is best reserved for either the inciting incident at the first plot point or as the terrible event of the third quarter of the book. So instead of assassination, we should resort to creativity.

This is where the outline can provide some structure, and keep you moving forward. I will know what should happen in the first quarter, the middle, and the third quarter of the story. Also, because I know how it should end, I can more easily write to those plot points by filling in the blanks between, and the story will have cohesion.

Think about what launches a great story:

The protagonist has a problem.

You have placed them in a setting at a given moment, and shown the environment in which they live.

You have unveiled the inciting incident.

You know what they want, but you aren’t sure how far they will go to achieve it.

Now you need to decide what hinders the protagonist and prevents them from resolving the problem. While you are laying the groundwork for this keep in mind that we want to evoke three things:

- Empathy/identification with the protagonist

- Believability

- Tension

We want the protagonist to be a sympathetic character whom the reader can identify with; one who the reader can immerse themselves in, living the story through his/her adventures.

But for NaNoWriMo, speed is everything. I need to get my 1,667 words every day, and I can’t take the time to sit back and ponder what to write next.

I find that this is where a loose outline helps me write quickly. Readers want the hindrances and barriers the protagonist faces to feel real. A loose guide helps me develop setups for the central events. This enables me to quickly lay down the narrative that shows the payoffs (either negative or positive) to advance the story: action and reaction.

Some authors resort to “idle conversation writing” when they are temporarily out of ideas. If you can resist the temptation, please do so—it’s fatal to an otherwise good story. Save all your random think-writing off-stage in a background file, if giving your characters a few haphazard, pointless exchanges helps jar an idea loose. (However, for purposes of wordcount, if you wrote it, you can count it!)

One failing of NaNo Novels in their rough draft form is their unevenness. Try not to introduce random things into a scene unless they are important. Remember, to show the reader something is to foreshadow it, and the reader will wonder why a casual person or thing was so important they had to be foreshadowed.

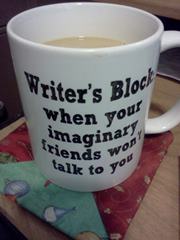

Both over planning and under planning can lead to a book that is stalled and a writer who believes they have ‘writers’ block.’ For me a happy medium lies in a general outline, done as a brief storyboard:

What has prevented you from writing in the past? Did you get busy? Did you sleep in? Did you feel uncreative? These are mental roadblocks we all experience. The whole point of NaNoWriMo is to develop the ability to work through these hindrances.

Remember, you are a superhero with a keyboard, slaying the monsters of indolence and lack of creativity.

My dear friend, author Stephen Swartz, had this to say on the subject of over planning: “The story is your ship, the NaNo your ocean. Let the keyboard be your wind! May metaphors drive you to new lands!”

I completely agree. Do a little planning, but write like the wind, and let the story take you where it will.

Credits and Attributions

The Pros and Cons of Plotters and Pantsers by The Magic Violinist, The Write Practice, http://thewritepractice.com/plotters-pantsers/ © 2017

Pantser vs. Plotter

Pantser vs. Plotter  Planster

Planster