Today is part two of my October NaNo Prep series. This post explores character creation. Often, we have ideas for great characters but no story for them. For those who don’t write daily, it’s a way to help get you into the habit.

These exercises will only take a few minutes unless you want to spend more time on them. They’re just a warmup, getting you thinking about your writing project. Each post will tackle a different aspect of preparation and won’t take more than ten or fifteen minutes to complete. By the end of this series, my goal is for you to have a framework that will get your project started.

These exercises will only take a few minutes unless you want to spend more time on them. They’re just a warmup, getting you thinking about your writing project. Each post will tackle a different aspect of preparation and won’t take more than ten or fifteen minutes to complete. By the end of this series, my goal is for you to have a framework that will get your project started.

SO—let’s begin with characters. Some will be heroes, others will be sidekicks, and still others will be villains to one degree or another.

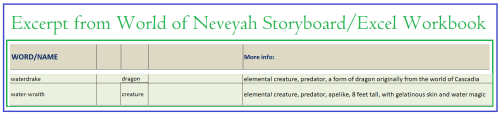

I recommend you create a file that contains all the ideas you have in regard to your fictional world, including the personnel files you are creating. I list all my information in an Excel workbook for each book or series, but you can use any kind of document, even handwritten. You just need to write your ideas down. See my post, Ensuring Consistency: the Stylesheet.

I recommend you create a file that contains all the ideas you have in regard to your fictional world, including the personnel files you are creating. I list all my information in an Excel workbook for each book or series, but you can use any kind of document, even handwritten. You just need to write your ideas down. See my post, Ensuring Consistency: the Stylesheet.

Perhaps you already have an idea for the characters you intend to people your story with. Even if you don’t, take a moment to sit back and think about who they might be.

No matter the genre or the setting, humans will be humans and have certain recognizable personality traits.

So, who is the protagonist of my intended story? Truthfully, in some aspect or another, they will be the person I wish I were. That is how it always is for me—living a fantasy in the safe environment of the novel. Bilbo was J.R.R. Tolkien’s younger self, an inexperienced man discovering the broader world through his wartime experiences. Luke Skywalker was the hero George Lucas always wanted to be.

So, who is the protagonist of my intended story? Truthfully, in some aspect or another, they will be the person I wish I were. That is how it always is for me—living a fantasy in the safe environment of the novel. Bilbo was J.R.R. Tolkien’s younger self, an inexperienced man discovering the broader world through his wartime experiences. Luke Skywalker was the hero George Lucas always wanted to be.

For me, a story is the people—the characters, their interactions, their thoughts, and how the arc of the plot changes them. In return, writing the events they experience enables me to see my values and beliefs more clearly. I begin to understand myself.

I feel an author should introduce however many characters it takes to tell the story. But we must also use common sense. Too many named characters is too many.

So, let’s start with one character, our protagonist. First, we need a name, even if it’s just a placeholder. I have learned to keep in mind simplicity of spelling and ease of pronunciation when I name my characters. My advice is to keep it simple and be vigilant—don’t give two characters names that are nearly identical and that begin and end with the same letter.

Have you ever read a book where you couldn’t figure out how to pronounce a name? Speaking as a reader, it aggravates me no end: Brvgailys tossed her lush hair over her shoulder. (BTW—I won’t be recommending that book to anyone.) (Ever.)

You might think of the unusual spellings as part of your world-building. I get that, but there is another reason to consider making names easily pronounceable, no matter how fancy and other-worldly they look if spelled oddly. You may decide to have your book made into an audiobook, and the process will go more smoothly if your names are uncomplicated. I only have one audiobook, and the experience of making that book taught me to spell names simply.

Now that we have a name, even if it’s just a placeholder, we can move on to the next step. Then we write a brief description. One thing that helps when creating a character is identifying the verbs embodied by each individual’s personality. What pushes them to do the crazy stuff they do?

The person our protagonist appears to be on page one, and the motivations they start out with must be clearly defined. Identifying these two aspects is central to who your character is:

- VOID: Each person lacks something, a void in their life. What need drives them?

- VERBS: What is their action word, the verb that defines their personality? How does each character act and react on a gut level?

If we know their void, we should write it down now, along with any quirky traits they may have. Next, we decide on verbs that will be the driving force of their personality at the story’s opening. Add some adjectives to describe how they interact with the world and assign nouns to show their characteristics.

If we know their void, we should write it down now, along with any quirky traits they may have. Next, we decide on verbs that will be the driving force of their personality at the story’s opening. Add some adjectives to describe how they interact with the world and assign nouns to show their characteristics.

Example:

Maia (healer, 25 yrs. old, black ringlets, dark skin, brown eyes with golden flecks.) Parents were mages, father an earth-mage who builds and repairs levees in the cities along the River Fleet. VOID: Mother murdered by a priest of the Bull God. Father never got over it. Maia is not good with tools and unintentionally breaks or loses things. VERBS: Nurture. Protect. ADJECTIVES: awkward, impulsive, focused, motivated, loyal, caring. NOUNS: empathy, purpose, wit.

Once I do this for the protagonist and her sidekicks, I will ask myself, “Who is the antagonist? What do they want?”

Nord, a tribeless mage, turned rogue. Warlord desiring control of Kyrano Citadel. Intent on making a better life for his children and will achieve it at any cost. VOID: Born into a poor woodcutter’s family. Father abusive drunk, mother weak, didn’t protect him. VERBS: Fight, Desire, Acquire. ADJECTIVES: arrogant, organized, decisive, direct, focused, loyal. NOUNS: purpose, leadership, authority.

Our characters will meet and interact with other characters. Some are sidekicks, and some are enemies. Don’t bother giving pass-through characters’ names, as a name shouts that a character is an integral part of the story and must be remembered.

Your project could be anything from a memoir to an action-adventure. No matter the genre, the characters must be individuals with secrets only they know about themselves. This is especially true if you are writing a memoir. Over the next few days, list these traits as they come to mind.

Name your characters as they occur to you. Assign genders and preferences and give a loose description of their physical traits. If you like, use your favorite movie stars or television stars as your prompts.

We are changed in real life by what we experience as human beings. Each person grows and develops in a way that is distinctively them. Some people become jaded and cynical. Others become more compassionate and forgiving.

Everyone perceives things in a unique way and is affected differently than their companions. In a given situation, other people’s gut reactions vary in intensity from mine or yours. Whether we are writing a romance, a sci-fi novel, a literary novel, or even a memoir, we must know who the protagonist is on page one.

That means we need to create their backstory, just a paragraph or two. This will grow in length over time as the story takes shape. As we write each personnel file, we will begin to see their past, present, and possible future.

Making lists of names is essential. You want their spellings to remain consistent and being able to return to what you initially planned is a big help later on. When we commence writing the actual narrative, each character will have an arc of growth, and sometimes names will change as the story progresses. Do remember to make notes of those changes.

Making lists of names is essential. You want their spellings to remain consistent and being able to return to what you initially planned is a big help later on. When we commence writing the actual narrative, each character will have an arc of growth, and sometimes names will change as the story progresses. Do remember to make notes of those changes.

Heroes who arrive perfect in every way on page one are uninteresting. For me, the characters and all their strengths and flaws are the core of any story. The events of the piece exist only to force growth upon them.

Posts in this series to date:

#NaNoWriMo prep part 1: Deciding on the Project #amwriting

Credits and Attributions:

Dustcover of the first edition of The Hobbit, taken from a design by the author, J.R.R. Tolkien.

Rather than obsess about my lack of creativity, I decided to have fun with it. Several young writers in my NaNoWriMo region have said they used a plot generator to jumpstart their ideas, so I thought I’d give that a try.

Rather than obsess about my lack of creativity, I decided to have fun with it. Several young writers in my NaNoWriMo region have said they used a plot generator to jumpstart their ideas, so I thought I’d give that a try. Cursed

Cursed This plot generator has clearly been studying J.R.R. Tolkien, as it has managed to plagiarize the first paragraph of The Hobbit right down to the punctuation.

This plot generator has clearly been studying J.R.R. Tolkien, as it has managed to plagiarize the first paragraph of The Hobbit right down to the punctuation. Even if you have an MFA degree, you could spend a lifetime learning the craft and never learn all there is to know about the subject. We join writing groups, buy books, and most importantly, read. We analyze what we have read and figure out what we liked or disliked about it. Then, we try to apply what we learned to our work.

Even if you have an MFA degree, you could spend a lifetime learning the craft and never learn all there is to know about the subject. We join writing groups, buy books, and most importantly, read. We analyze what we have read and figure out what we liked or disliked about it. Then, we try to apply what we learned to our work.

You have just spent the last year or more combing through your novel. This is another example of silly advice that doesn’t consider how complex and involved the process of getting a book written and published is. I love writing, but when you have been working on a story through five drafts, it can be hard to get excited about making one more trip through it, looking for typos.

You have just spent the last year or more combing through your novel. This is another example of silly advice that doesn’t consider how complex and involved the process of getting a book written and published is. I love writing, but when you have been working on a story through five drafts, it can be hard to get excited about making one more trip through it, looking for typos. When we first embark on learning this craft, we latch onto handy, easy-to-remember mantras because we want to educate ourselves. Unless we’re fortunate enough to have a formal education in the art of writing, we who are just beginning must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides.

When we first embark on learning this craft, we latch onto handy, easy-to-remember mantras because we want to educate ourselves. Unless we’re fortunate enough to have a formal education in the art of writing, we who are just beginning must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides. We can easily bludgeon our work to death in our effort to fit our square work into round holes. In the process of trying to obey all the rules, every bit of creativity is shaved off the corners. A great story with immense possibilities becomes boring and difficult to read. As an avid reader and reviewer, I see this all too often.

We can easily bludgeon our work to death in our effort to fit our square work into round holes. In the process of trying to obey all the rules, every bit of creativity is shaved off the corners. A great story with immense possibilities becomes boring and difficult to read. As an avid reader and reviewer, I see this all too often. They often detail an experience or event and how it shaped the author on a personal level. For those of us who wish to earn actual money from writing, the narrative essay appeals to a broader audience than short stories, so more magazine editors are looking for them.

They often detail an experience or event and how it shaped the author on a personal level. For those of us who wish to earn actual money from writing, the narrative essay appeals to a broader audience than short stories, so more magazine editors are looking for them. But just what is an essay in the first place? The primary purpose of an essay is to offer readers thought-provoking content. The narrative essay conveys our ideas in a palatable form, so writing this sort of piece requires authors to have some idea of the craft of writing.

But just what is an essay in the first place? The primary purpose of an essay is to offer readers thought-provoking content. The narrative essay conveys our ideas in a palatable form, so writing this sort of piece requires authors to have some idea of the craft of writing. HOWEVER – if you want to be published by a reputable magazine, you must pay strict attention to grammar and editing.

HOWEVER – if you want to be published by a reputable magazine, you must pay strict attention to grammar and editing. Don’t be discouraged by rejection. Rejection happens far more frequently than acceptance, so don’t let fear of rejection keep you from writing pieces you’re emotionally invested in.

Don’t be discouraged by rejection. Rejection happens far more frequently than acceptance, so don’t let fear of rejection keep you from writing pieces you’re emotionally invested in. Tad Williams’s

Tad Williams’s When the story opens with the first novel,

When the story opens with the first novel,  By the end of the third book,

By the end of the third book,  Fate vs. free will

Fate vs. free will But not every author has that option.

But not every author has that option. In most standard book contracts, royalty terms for authors are terrible, and this is especially true for eBook sales. Most eBooks are sold through online retailers like Amazon. If you’re a traditionally published author and your publisher priced your eBook at $9.99, this is how the Amazon numbers break out. No matter what you think of Amazon, it is still the Big Fish in the Publishing and Bookselling Pond:

In most standard book contracts, royalty terms for authors are terrible, and this is especially true for eBook sales. Most eBooks are sold through online retailers like Amazon. If you’re a traditionally published author and your publisher priced your eBook at $9.99, this is how the Amazon numbers break out. No matter what you think of Amazon, it is still the Big Fish in the Publishing and Bookselling Pond: However, to be considered for a traditional contract, you should hire an editor, beta reader, and proofreader to ensure the manuscript you submit to an agent or editor demonstrates your ability to turn out a good, professional product.

However, to be considered for a traditional contract, you should hire an editor, beta reader, and proofreader to ensure the manuscript you submit to an agent or editor demonstrates your ability to turn out a good, professional product. Regardless of your publishing path, you must budget for certain things. You can’t expect your royalties to pay for them early in your career – and many award-winning authors must still work at their day jobs to pay their bills.

Regardless of your publishing path, you must budget for certain things. You can’t expect your royalties to pay for them early in your career – and many award-winning authors must still work at their day jobs to pay their bills. Conferences are an extension of the self-education process. I have discovered so much about the craft of writing, the genres I write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things I could only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining

Conferences are an extension of the self-education process. I have discovered so much about the craft of writing, the genres I write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things I could only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining

Sometimes I am invited to participate in panels or offer a workshop, and I can share my experiences with others. Either way, I learn things. In September, I will be on a panel with

Sometimes I am invited to participate in panels or offer a workshop, and I can share my experiences with others. Either way, I learn things. In September, I will be on a panel with  Time interests me because I mostly write fantasy, although I write contemporary short fiction and poetry. Fantasy, and all speculative fiction, relies heavily on worldbuilding, and managing time is a facet of that skill.

Time interests me because I mostly write fantasy, although I write contemporary short fiction and poetry. Fantasy, and all speculative fiction, relies heavily on worldbuilding, and managing time is a facet of that skill. HERE is where I confess my great regret: in 2008, a lunar calendar seemed like a good thing while creating my first world.

HERE is where I confess my great regret: in 2008, a lunar calendar seemed like a good thing while creating my first world. In an even worse bout of predictability, I went with the names we currently use when I named the days, only I twisted them a bit and gave them the actual Norse god’s name. (The gods and goddesses of Neveyah are not Norse.)

In an even worse bout of predictability, I went with the names we currently use when I named the days, only I twisted them a bit and gave them the actual Norse god’s name. (The gods and goddesses of Neveyah are not Norse.) I LEARNED from my mistakes – the timeline for the Billy’s Revenge 3-book series, Huw the Bard, Billy Ninefingers, and Julian Lackland, uses the familiar calendar we use today.

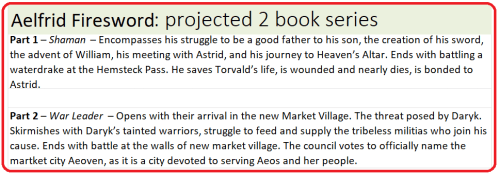

I LEARNED from my mistakes – the timeline for the Billy’s Revenge 3-book series, Huw the Bard, Billy Ninefingers, and Julian Lackland, uses the familiar calendar we use today. Thus, it makes sense to consider whether your story is complex enough to hold up well across a series.

Thus, it makes sense to consider whether your story is complex enough to hold up well across a series. If you are done with your first draft and are just now realizing your novel could be the beginning of a saga, you should consider making notes as to what the future holds for your crew beyond the end. Otherwise, you may find yourself writing a continuation of book one, but with no goal, no purpose.

If you are done with your first draft and are just now realizing your novel could be the beginning of a saga, you should consider making notes as to what the future holds for your crew beyond the end. Otherwise, you may find yourself writing a continuation of book one, but with no goal, no purpose. So, for a saga you might want to draw up an overall story arc for the entire series. For a standalone book featuring a recurring character, you likely won’t need to have an all-encompassing projected arc.

So, for a saga you might want to draw up an overall story arc for the entire series. For a standalone book featuring a recurring character, you likely won’t need to have an all-encompassing projected arc. Think about it – the universe contains all we can measure and know, all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all forms of matter and energy. It likes balls and spirals and has a structure that repeats itself. This is reflected in the shape and behavior of the smallest particles to the largest quasars.

Think about it – the universe contains all we can measure and know, all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all forms of matter and energy. It likes balls and spirals and has a structure that repeats itself. This is reflected in the shape and behavior of the smallest particles to the largest quasars. First off, no matter our conscious thoughts regarding the universe and God, writers don’t exist in reality. We exist in what we think reality is, and collectively, we create it as we go along, for good or ill.

First off, no matter our conscious thoughts regarding the universe and God, writers don’t exist in reality. We exist in what we think reality is, and collectively, we create it as we go along, for good or ill. But if you make a map of what you can see, your own

But if you make a map of what you can see, your own  As I wrote, the outline for that first book took its shape. The written universe is in constant flux, and the storyboard records the changes and keeps the fabric of time from warping.

As I wrote, the outline for that first book took its shape. The written universe is in constant flux, and the storyboard records the changes and keeps the fabric of time from warping. Once I have decided the proposed length, I know where the turning points are and what should happen at each. The outline ensures an arc to both the overall story and the characters’ personal growth.

Once I have decided the proposed length, I know where the turning points are and what should happen at each. The outline ensures an arc to both the overall story and the characters’ personal growth.