November is over, and I did achieve my goal of writing a chapter a day for all 30 days. However, the story is not finished, and a great deal of work still remains to be done. In between working on other projects, I will spend several months doing three things:

- Delving deeper into character arcs.

- Firming up the plot

- Identifying and cutting the chapters that don’t advance the main character’s story and turn them into short stories.

I always start with the characters.

As stories unfold on paper, new characters enter. They bring their dramas and the story goes in a different direction than was planned. When I meet these imaginary people, I assign their personalities a verb and a noun.

As stories unfold on paper, new characters enter. They bring their dramas and the story goes in a different direction than was planned. When I meet these imaginary people, I assign their personalities a verb and a noun.

As an example of how I work, let’s look at four characters from my novel, Julian Lackland, which was published in 2020. Each side character impacts Julian’s life for good or ill.

This novel had a rough beginning, and an even harder path to final product. I nearly shelved it forever, but I had the good fortune to attend a seminar given by romance author, Damon Suede. THAT high-energy seminar changed how I approached the story.

I took the story back to its foundations and in the final rewrite, I made a point of looking for the two words that best describe how each point-of-view character sees themselves. It changed everything, allowing the story to be shown the way I saw it in my mind.

Julian’s noun is chivalry (Gallantry, Bravery, Daring, Courtliness, Valor, Love). He sees himself as a good knight and puts all his effort into being that person. He is in love with both Mags and Beau.

Julian’s noun is chivalry (Gallantry, Bravery, Daring, Courtliness, Valor, Love). He sees himself as a good knight and puts all his effort into being that person. He is in love with both Mags and Beau.

Beau’s noun is bravery (Courage, Loyalty, Daring, Gallantry, Passion). Golden Beau is also a good knight, but his view of himself is more pragmatic. He is Julian’s protector and is in love with both Mags and Julian.

Lady Mags’s noun is audacity (Daring, Courage). Mags defied her noble father and ran away from an arranged marriage to a duke in order to swing her sword as a mercenary. She will win at any cost and is not above lying or cheating to do so. She is in love with both Beau and Julian.

Bold Lora’s noun is bravado (Boldness, Brashness). Lora is in it for the fame. She doesn’t care about the people she is hired to protect, and makes enemies among every crew she is hired to serve in. As one unimpressed side character puts it, “If Lora rescues a cat from a tree, she wants songs of the amazing deed sung in every tavern.”

The way we see ourselves is the face we present to the world. These self-conceptions color how my characters react at the outset. By the end of the story, how they see themselves has changed because their experiences will both break and remake them.

Next, we assign a verb that describes their gut reactions, which will guide how they react to every situation. They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth. Again, we also look at sub-verbs and synonyms:

Next, we assign a verb that describes their gut reactions, which will guide how they react to every situation. They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth. Again, we also look at sub-verbs and synonyms:

Julian has 2 Verbs. They are: Defend, Fight, (Preserve, Uphold, Protect)

Beau’s 2 Verbs are: Protect, Fight (Defend, Shield, Combat, Dare)

Lady Mags’s 2 Verbs are: Fight, Defy (Compete, Combat, Resist)

Bold Lora’s 2 Verbs are: Desire, Acquire (Want, Gain, Own)

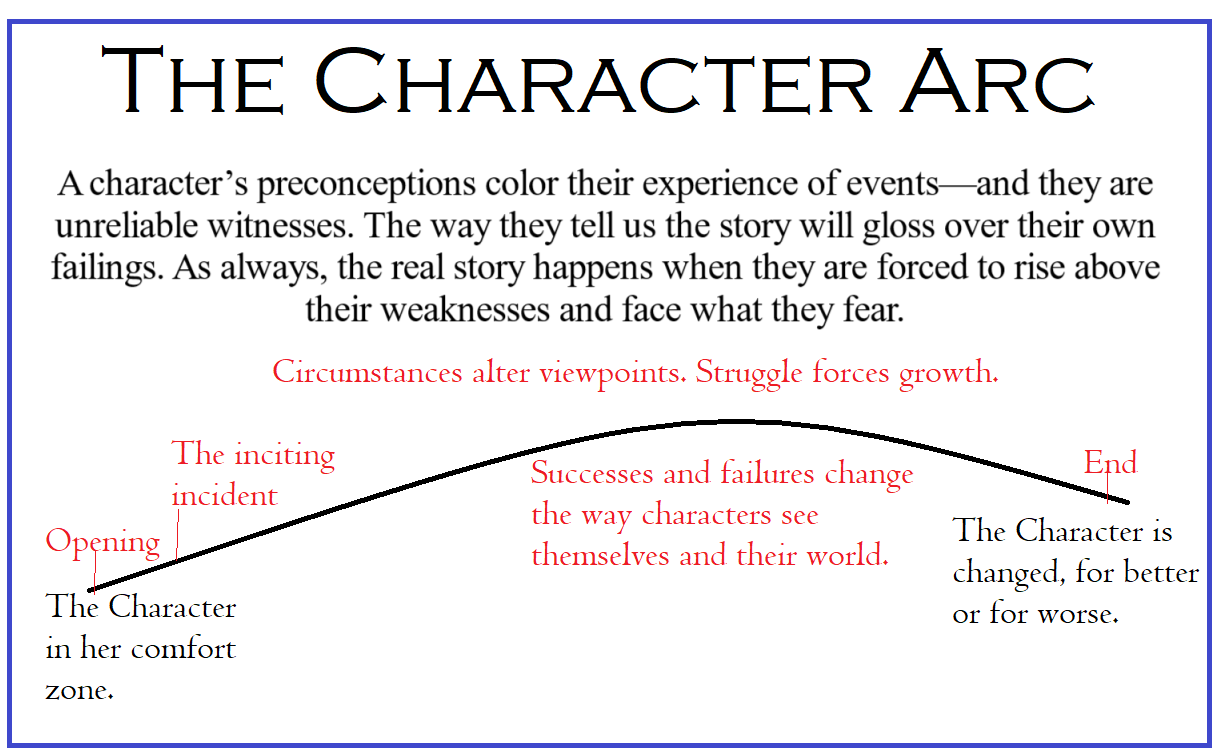

A character’s preconceptions color their experience of events—and they are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their own failings. As always, the real story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

As readers we see the story through the protagonist’s eyes, which shades how we perceive the incidents.

When I write my characters, I know how they believe they will react in a given situation. Why? Because I have drawn their portraits using words:

Julian must Fight for and Defend Chivalry. Julian’s commitment to defending innocents against inhumanity is his void, and ultimately it breaks his mind.

Golden Beau must Fight for and Protect Bravery. Beau’s deep love and commitment to protecting and concealing Julian’s madness is his void. Ultimately, it breaks Beau’s health.

Lady Mags must Fight for and Defy Audacity. She’s at war with herself in regard to her desire for a life with Julian and Beau. Despite the two knights’ often-expressed wish to have her with them, a triangular marriage goes against society’s conventions more than even a rebel like Mags is willing to do. That war destroys her chance at happiness and is her void.

Bold Lora must Fight for and Acquire Fame. She believes that to be famous is to be loved. Orphaned at a young age and raised by various indifferent guardians, she just wants to be loved by everyone. Julian’s fame has made him the object of her obsession. If she can own him, she will be famous, adored by all. This desperate striving for fame is Lora’s void.

The verb (action word) that drives them and the noun (object of the action) are the character traits that hold them back. It is their void, the emptiness they must fill.

Have you thought about the two words that describe the primary weaknesses of your characters, the thing that could be their ultimate ruin? In the case of Julian’s story, it was:

Have you thought about the two words that describe the primary weaknesses of your characters, the thing that could be their ultimate ruin? In the case of Julian’s story, it was:

Julian Lackland: Obsession and Honor

Golden Beau Baker: Love and Loyalty

Lady Mags De Leon: Stubbornness and Fear (of Entrapment)

Bold Lora: Fear (of Being) Forgotten

So, in the novel, Julian Lackland, a girl who was ignored by everyone, a child who’d lived on the outside looking in and who was fostered by indifferent relatives, decides that the one person who had ever shown her kindness should become her lover. If she could have Julian, fame would follow.

The way she goes about it changes everything and is the core of Julian’s character arc.

Julian Lackland took ten years to get from the 2010 NaNoWriMo novel to the finished product. He spawned the books Huw the Bard and Billy Ninefingers, both of which were written and published before the final version of Julian’s story was completed. Billy and Huw play a huge role in shaping Julian’s life.

Julian Lackland took ten years to get from the 2010 NaNoWriMo novel to the finished product. He spawned the books Huw the Bard and Billy Ninefingers, both of which were written and published before the final version of Julian’s story was completed. Billy and Huw play a huge role in shaping Julian’s life.

Placing a verb phrase (Fight for and Acquire) before a noun (Fame) in a personality description illuminates their core conflict. It lays bare their flaws and opens the way to building new strengths as they progress through the events.

Or it will be their destruction.

By the end of the book, the characters must have changed. Some have been made stronger and others weaker – but all must have an arc to their development.

Sometimes, as in the case of Julian Lackland, the path to publication is fraught with misery. Other times, the book writes itself and flies out the door. Who knows how my current unfinished novel will end? It’s in the final stretch, but nothing is certain.

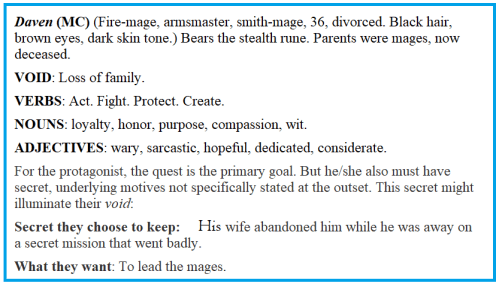

I am a step ahead in this process, though. I already know my characters’ weaknesses, their verbs and nouns. As I learned from my experience writing Julian’s novel, I just need to know who they think they are, and then I must write the situations they believe they can’t handle.

I’m not a Romance writer, but I do write about relationships. Readers expecting a standard romance would be disappointed in my work which is solidly fantasy. The people in my tales fall in love, and while they don’t always have a happily ever after, most do. The other aspect that would disappoint a Romance reader is the shortage of smut.

I’m not a Romance writer, but I do write about relationships. Readers expecting a standard romance would be disappointed in my work which is solidly fantasy. The people in my tales fall in love, and while they don’t always have a happily ever after, most do. The other aspect that would disappoint a Romance reader is the shortage of smut.

In his book

In his book

When a beta reader tells me the relationship seems forced, I go back to the basics and make an outline of how that relationship should progress from page one through each chapter. I make a detailed note of what their status should be at the end. This gives me jumping-off points so that I don’t suffer from brain freeze when trying to show the scenes.

When a beta reader tells me the relationship seems forced, I go back to the basics and make an outline of how that relationship should progress from page one through each chapter. I make a detailed note of what their status should be at the end. This gives me jumping-off points so that I don’t suffer from brain freeze when trying to show the scenes. I think our characters have to be a little clueless about Romance, even if they are older. They need to doubt, need to worry. They need to fear they don’t have a chance, either to complete their quest or to find love.

I think our characters have to be a little clueless about Romance, even if they are older. They need to doubt, need to worry. They need to fear they don’t have a chance, either to complete their quest or to find love. When I begin writing a first draft, I try to approach writing each scene as if I were shooting a movie. We know that each conversation is an event that must advance the story, but it must also give us glimpses of who each person is.

When I begin writing a first draft, I try to approach writing each scene as if I were shooting a movie. We know that each conversation is an event that must advance the story, but it must also give us glimpses of who each person is. Having the fundamentals of the conversation to work with sharpens the scene in my mind, enabling me to frame it properly. Once I know what they are talking about and have the rudimentary dialogue straight, I add the scenery. Then, I insert the props and add the speech tags. The interaction grows, shedding more light on their relationship.

Having the fundamentals of the conversation to work with sharpens the scene in my mind, enabling me to frame it properly. Once I know what they are talking about and have the rudimentary dialogue straight, I add the scenery. Then, I insert the props and add the speech tags. The interaction grows, shedding more light on their relationship. My above sample is not perfect, as it is from the first draft of a short story I never actually finished, but you get the idea. We learn more about the characters’ relationship with each other and see their place in this environment. The layers that form this scene are:

My above sample is not perfect, as it is from the first draft of a short story I never actually finished, but you get the idea. We learn more about the characters’ relationship with each other and see their place in this environment. The layers that form this scene are: Set dressing (the props you place in the scene) shows the immediate environment. Having characters interact with props provides opportunities to insert hints that a deeper backstory exists. However, only have them interact with props that are organic or crucial to the story. This eliminates the problem of

Set dressing (the props you place in the scene) shows the immediate environment. Having characters interact with props provides opportunities to insert hints that a deeper backstory exists. However, only have them interact with props that are organic or crucial to the story. This eliminates the problem of  By beginning with the conversation and envisioning each scene as if I were filming a movie, I can flesh it out and show everything the reader needs to hang their imagination on. The reader’s mind will supply the details of the immediate setting depending on the clues I give.

By beginning with the conversation and envisioning each scene as if I were filming a movie, I can flesh it out and show everything the reader needs to hang their imagination on. The reader’s mind will supply the details of the immediate setting depending on the clues I give. In his book,

In his book,  Batman is a

Batman is a  Apollo 13 (April 11–17, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the

Apollo 13 (April 11–17, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the  No matter what genre we write in, when we design the story, we build it around a need that must be fulfilled, a quest of some sort.

No matter what genre we write in, when we design the story, we build it around a need that must be fulfilled, a quest of some sort.

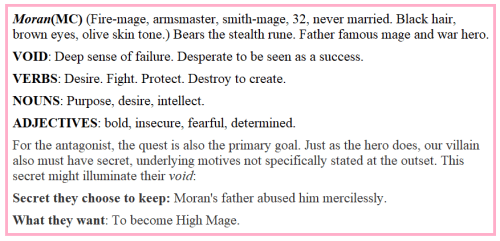

I recently had a manuscript undergo a complete change from what I originally planned. The original antagonist had such an engaging story that he had become more important to me than the protagonists.

I recently had a manuscript undergo a complete change from what I originally planned. The original antagonist had such an engaging story that he had become more important to me than the protagonists. As a reader, I dislike discovering the author is at a loss as to what their protagonist wants. Without that impetus, they don’t have a good reason for the villain to be there either. Random events inserted to keep things interesting don’t advance the story, but motivation does.

As a reader, I dislike discovering the author is at a loss as to what their protagonist wants. Without that impetus, they don’t have a good reason for the villain to be there either. Random events inserted to keep things interesting don’t advance the story, but motivation does. You’ve taken them through two revisions and think these characters are awesome, perfectly drawn as you intend. The overall theme of the narrative supports the plot arc, and the events are timed perfectly, so the pacing is good.

You’ve taken them through two revisions and think these characters are awesome, perfectly drawn as you intend. The overall theme of the narrative supports the plot arc, and the events are timed perfectly, so the pacing is good. But in real life, I often find little distinction between heroes and villains. Heroes are often jackasses who need to be taken down a notch. Villains will extort protection money from a store owner and then turn around and open a soup kitchen to feed the unemployed.

But in real life, I often find little distinction between heroes and villains. Heroes are often jackasses who need to be taken down a notch. Villains will extort protection money from a store owner and then turn around and open a soup kitchen to feed the unemployed. Both heroes and villains must have possibilities – the chance that the villain might be redeemed, or the hero might become the villain. As an avid gamer, I think of this as the “

Both heroes and villains must have possibilities – the chance that the villain might be redeemed, or the hero might become the villain. As an avid gamer, I think of this as the “ In Final Fantasy VII, the 1997 game that started it all, we meet Cloud Strife, a mercenary with a mysterious past. Gradually, we discover that, unbeknownst to himself, he is living a lie that he must face and overcome to be the hero we all need him to be.

In Final Fantasy VII, the 1997 game that started it all, we meet Cloud Strife, a mercenary with a mysterious past. Gradually, we discover that, unbeknownst to himself, he is living a lie that he must face and overcome to be the hero we all need him to be.

I try to keep the ensemble narrow in my work, limiting points of view to only one, two, or three characters at most. I keep the core cast limited to four or five, as it takes a lot of effort to show more people than that as being separate and unique.

I try to keep the ensemble narrow in my work, limiting points of view to only one, two, or three characters at most. I keep the core cast limited to four or five, as it takes a lot of effort to show more people than that as being separate and unique. Moriarty’s characters are immediately engaging. They sucked me into their world in the opening pages. I couldn’t set the book down, as I wanted to know everyone’s dark secrets. I was hooked; I had to understand what led these people to book themselves into that exceedingly unusual health spa.

Moriarty’s characters are immediately engaging. They sucked me into their world in the opening pages. I couldn’t set the book down, as I wanted to know everyone’s dark secrets. I was hooked; I had to understand what led these people to book themselves into that exceedingly unusual health spa. The guests are immediately thrust into an unknown and possibly dangerous environment. The food they are offered is high quality but not what they are used to and varies from guest to guest.

The guests are immediately thrust into an unknown and possibly dangerous environment. The food they are offered is high quality but not what they are used to and varies from guest to guest. Character Names. I list the essential characters by name and the critical places where the story will be set.

Character Names. I list the essential characters by name and the critical places where the story will be set. These exercises will only take a few minutes unless you want to spend more time on them. They’re just a warmup, getting you thinking about your writing project. Each post will tackle a different aspect of preparation and won’t take more than ten or fifteen minutes to complete. By the end of this series, my goal is for you to have a framework that will get your project started.

These exercises will only take a few minutes unless you want to spend more time on them. They’re just a warmup, getting you thinking about your writing project. Each post will tackle a different aspect of preparation and won’t take more than ten or fifteen minutes to complete. By the end of this series, my goal is for you to have a framework that will get your project started. I recommend you create a file that contains all the ideas you have in regard to your fictional world, including the personnel files you are creating. I list all my information in an Excel workbook for each book or series, but you can use any kind of document, even handwritten. You just need to write your ideas down. See my post,

I recommend you create a file that contains all the ideas you have in regard to your fictional world, including the personnel files you are creating. I list all my information in an Excel workbook for each book or series, but you can use any kind of document, even handwritten. You just need to write your ideas down. See my post,  So, who is the protagonist of my intended story? Truthfully, in some aspect or another, they will be the person I wish I were. That is how it always is for me—living a fantasy in the safe environment of the novel. Bilbo was J.R.R. Tolkien’s younger self, an inexperienced man discovering the broader world through his wartime experiences. Luke Skywalker was the hero George Lucas always wanted to be.

So, who is the protagonist of my intended story? Truthfully, in some aspect or another, they will be the person I wish I were. That is how it always is for me—living a fantasy in the safe environment of the novel. Bilbo was J.R.R. Tolkien’s younger self, an inexperienced man discovering the broader world through his wartime experiences. Luke Skywalker was the hero George Lucas always wanted to be. If we know their void, we should write it down now, along with any quirky traits they may have. Next, we decide on verbs that will be the driving force of their personality at the story’s opening. Add some adjectives to describe how they interact with the world and assign nouns to show their characteristics.

If we know their void, we should write it down now, along with any quirky traits they may have. Next, we decide on verbs that will be the driving force of their personality at the story’s opening. Add some adjectives to describe how they interact with the world and assign nouns to show their characteristics. Making lists of names is essential. You want their spellings to remain consistent and being able to return to what you initially planned is a big help later on. When we commence writing the actual narrative, each character will have an arc of growth, and sometimes names will change as the story progresses. Do remember to make notes of those changes.

Making lists of names is essential. You want their spellings to remain consistent and being able to return to what you initially planned is a big help later on. When we commence writing the actual narrative, each character will have an arc of growth, and sometimes names will change as the story progresses. Do remember to make notes of those changes. Unfortunately, although we asked for a ground-floor condo, we were assigned a second-floor unit. My husband is managing the stairs – slowly. On the good side, we have the god’s-eye view of a wide stretch of beach, the perfect deck overlooking it all.

Unfortunately, although we asked for a ground-floor condo, we were assigned a second-floor unit. My husband is managing the stairs – slowly. On the good side, we have the god’s-eye view of a wide stretch of beach, the perfect deck overlooking it all. Writing is going as well as ever, a little up and down. I’m building the framework for a new story, which I will begin writing on November 1st. The world is already built; it’s an established world with many things that are canon and can’t be changed. So, I’m working my way through the bag of tricks that help me jar things loose.

Writing is going as well as ever, a little up and down. I’m building the framework for a new story, which I will begin writing on November 1st. The world is already built; it’s an established world with many things that are canon and can’t be changed. So, I’m working my way through the bag of tricks that help me jar things loose. Protagonist HER: Anna Lundquist, an unemployed game developer. She inherited an old farm and has moved there. She embarks on creating her own business designing anime-based computer games. Anna is shy, not good with men unless discussing books or computer games. VOID: Loss of family. VERBS: Create, Build, Seek, Defend, Fight, Nurture. Modifiers: Adaptable, ambitious, focused, independent, industrious, mature, nurturing, private, resourceful, responsible, simple, thrifty.

Protagonist HER: Anna Lundquist, an unemployed game developer. She inherited an old farm and has moved there. She embarks on creating her own business designing anime-based computer games. Anna is shy, not good with men unless discussing books or computer games. VOID: Loss of family. VERBS: Create, Build, Seek, Defend, Fight, Nurture. Modifiers: Adaptable, ambitious, focused, independent, industrious, mature, nurturing, private, resourceful, responsible, simple, thrifty. Antagonist HIM: Matt Gentry, owner of MGPopularGames and Anna’s former boss, is angry at Anna for leaving his firm. On a skiing trip with an old fraternity brother who owns an art supply store in Starfall Ridge, he sees her entering Nic’s coffeeshop. Matt discovers that Anna is now living in that town. He learns she has started her own company and is building an anime-based RPG. He goes back to Seattle and files an injunction to stop her, claiming that he owns the rights to her intellectual property. VOID: Narcissist. VERBS: Possess, Control, Desire, Covet, Steal, Lie, Torment.

Antagonist HIM: Matt Gentry, owner of MGPopularGames and Anna’s former boss, is angry at Anna for leaving his firm. On a skiing trip with an old fraternity brother who owns an art supply store in Starfall Ridge, he sees her entering Nic’s coffeeshop. Matt discovers that Anna is now living in that town. He learns she has started her own company and is building an anime-based RPG. He goes back to Seattle and files an injunction to stop her, claiming that he owns the rights to her intellectual property. VOID: Narcissist. VERBS: Possess, Control, Desire, Covet, Steal, Lie, Torment.

Writing fiction allows me to put reality into more palatable chunks. It’s easier to cope with that way.

Writing fiction allows me to put reality into more palatable chunks. It’s easier to cope with that way. We all draw inspiration from real life, whether consciously or not. However, if we are writing fiction, we must never detail people we are acquainted with, even if we change their names.

We all draw inspiration from real life, whether consciously or not. However, if we are writing fiction, we must never detail people we are acquainted with, even if we change their names. The best thing is that you don’t actually know a thing about them other than they like a Double Tall Hazelnut Latte. Peoples’ conversations are unguarded in coffee shops, openly talking about what moves them or holds them back. They are lovers or haters, quiet or loud, and most importantly, anonymous.

The best thing is that you don’t actually know a thing about them other than they like a Double Tall Hazelnut Latte. Peoples’ conversations are unguarded in coffee shops, openly talking about what moves them or holds them back. They are lovers or haters, quiet or loud, and most importantly, anonymous.