One of the most difficult aspects of writing is creating the sense of history without resorting to an info dump. It is a fine line to walk, because too much information will cause the reader to stop reading, and not enough will also make them close the book. What we are looking for is a happy medium, a narrative that incorporates some history, but only the bits that are needed to move the story forward.

One of the most difficult aspects of writing is creating the sense of history without resorting to an info dump. It is a fine line to walk, because too much information will cause the reader to stop reading, and not enough will also make them close the book. What we are looking for is a happy medium, a narrative that incorporates some history, but only the bits that are needed to move the story forward.

That ability to create the past while describing the present is one that author L. E. Modesitt Jr. has, and is shown to its best advantage in his masterpiece Fall of Angels. Written in 1997, this is the sixth installment in one of the most enduring fantasy series of modern times, The Saga of Recluce.

This saga takes place over many generations and explores both sides of the conflict, with not usually more than two books dealing with a particular protagonist.

Modesitt Jr. knows his world. It is clear when you read his work that he understands the environments and societies he is writing about, and he knows the moral values of the three cultures who clash in this series of books. In Fall of Angels he takes the reader back a thousand years, to the origins of the conflict that is explored in the previous five books, but the world the angels find themselves stranded on feels familiar–because the author knows every aspect of his world.

In this series as a whole, Modesitt Jr. examines two radically different magics–the black of order vs the white of chaos. This is the central theme of each tale in the saga, and the protagonist is either of the black or white persuasion. In a few books there is a grey area of magic where the protagonist embodies both, but always the price of magic and the responsibility of those who wield it is a central theme in this series.

In Fall of Angels, Modesitt explores the side of order, the black magic of healing and building.

The story opens on the bridge of a battle-cruiser, the Winterlance. The crew is human, and are in the military service of the UFA, which is comprised of the planets of Heaven.

The crew of the Winterlance is from the various cold planets of Heaven. Most are from Sybra, the coldest planet, but a few are from Svenn, a more moderate planet. This limits where the Angels can comfortably live, making high altitudes their favored homes.

They are about to enter a battle from which they will likely not return, fighting against the Rationalists, the humans from warmer planets, and with whom they have been warring for thousands of years. The Rationalists are an extremely patriarchal society, and are also known as Demons.

In the opening pages we meet a crew that, by happenstance, is made up of women, with only three male crew members. Nylan is the ship’s engineer, and, as are all the officers, he is connected into the ships neuronet, the mental command center that completely controls the ship and its environment.

Ryba is the ship’s captain, and while she and Nylan have a sexual relationship, there is no doubt that she is in command. I didn’t say romantic, because though they sleep together and care for each other, there is no romance involved.

The energies expended during the battle are such that the Winterlance is thrown into an alternate universe, above a strange planet. With no way to return, they are forced to land.

Unfortunately the first thing that happens is they have landed on a world previously colonized. It probably happened in the same way, but by the Rationalists of the warmer worlds of Hell. The lord of the land immediately attacks them, and the conflict is on.

All Angels are not equal. Nylan is half-Svenn. The Sybrans cannot take the heat of their new world and are pretty much trapped in the cool mountains, but he can go lower, into the warmer areas, although he too suffers from the heat.

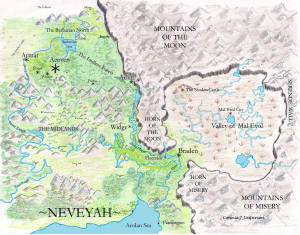

While the maps in this series are not very good, or really even useful, I feel sure the author must have a file with worldbuilding information for this series in it. Some forethought and planning went into creating Recluce, Candar, and the other continents that become locales for action in this series.

One type of tree is deciduous, with triangular gray leaves, and only loses half of them during the winter, the others curling up and remaining on the tree though the bitter cold. He knows the plant-life, and the animals native to this new world, and he knows the terrain and doesn’t contradict himself over the course of his narrative.

Modesitt Jr. shows us all of this, without resorting to telling. Information about the worlds of both Heaven and Hell and how the struggle to survive on the world of Recluce affects the marooned crew is doled out as needed, in conversations. The knowledge is dispensed organically, in such a way that the reader doesn’t see it as backstory.

Modesitt Jr. takes the concepts of traditional gender roles and twists them inside out. If she hadn’t been thrown out of her universe, Ryba would never have had the chance to rise any higher than she already had, as women are considered technically equal, but there is a glass ceiling that women rarely break through.

In their new world, Ryba makes sure the three men know they are now the ones with lesser stature. After viciously trouncing him bare-handed when he challenges her, Ryba coldly tells Gerlich, “I could amputate both your arms and you would still retain your stud value.” This comment is all we need: Ryba is determined to build a culture where women have all the power and men are simply a means to reproduction. She is deadly, calculating, and will ruthlessly use anyone to achieve her goal.

Her actions show us this.

Nylan is a strong man but he is not a leader, and feels like he has no other options, other than to march along with plans Ryba sets down for them. Using their failing technology he forges the weapons and builds their tower so they can survive the first winter in their mountain home. Ryba develops a talent for prophecy and becomes a slave to ensuring her own visions come true, while Nylan develops the foundations of order magic.

As events unfold and his relationship with Ryba disintegrates, he grows confused and unsure of what to do. He is a man with a temperate mind, believing in equality with neither sex having the upper hand. A few of the women feel the same way he does, but all are unwilling to go against Ryba, believing that while she is hard and unforgiving, she is better than the society created by the Rationalists, where women are property.

As events unfold and his relationship with Ryba disintegrates, he grows confused and unsure of what to do. He is a man with a temperate mind, believing in equality with neither sex having the upper hand. A few of the women feel the same way he does, but all are unwilling to go against Ryba, believing that while she is hard and unforgiving, she is better than the society created by the Rationalists, where women are property.

The characters themselves tell us this in their conversations, so the author doesn’t have to dump information.

Modesitt Jr. gives us a morality tale, as true speculative fiction does. But, rather than spelling everything out, he dishes it up through actions and conversations in such a way that the reader makes the connections themselves. While in many of his books Modesitt Jr. can be too cryptic, giving the reader little to no backstory to explain things, in Fall of Angels he strikes the perfect balance between too much information and not enough.

This balancing act between too much backstory and not enough creates a depth to the story that draws the reader in, suspending their disbelief, and holding their attention for the entire novel.

Writing a fictional novel is really the same as telling a whopping lie that you believe in with all your heart and keeping it straight for 80,000 words or more.

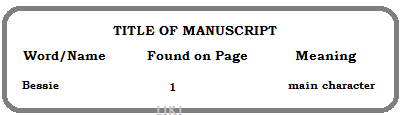

Writing a fictional novel is really the same as telling a whopping lie that you believe in with all your heart and keeping it straight for 80,000 words or more. When a manuscript comes across their desk, editors and publishers create a list of names, places, created words, and other things that may be repeated and that pertain only to that manuscript. This is called a stylesheet.

When a manuscript comes across their desk, editors and publishers create a list of names, places, created words, and other things that may be repeated and that pertain only to that manuscript. This is called a stylesheet. Place names evolve too, so maps are essential tools when you are building a world. Places written on a map tend to be ‘engraved in stone’ so to speak. Readers will wonder where the town of Maudy is when the only town on the map at the front of the book that comes close to that name is listed as Maury.

Place names evolve too, so maps are essential tools when you are building a world. Places written on a map tend to be ‘engraved in stone’ so to speak. Readers will wonder where the town of Maudy is when the only town on the map at the front of the book that comes close to that name is listed as Maury.