Artist: William Trost Richards (1833–1905)

Artist: William Trost Richards (1833–1905)

Title: Off the Coast of Cornwall

- Genre: landscape art

- Date: 1904

- Medium: oil on canvas

- Dimensions : Height: 55.9 cm (22 in); Width: 91.4 cm (35.9 in)

- Collection Private collection

- Inscriptions: Signature and date bottom left: W.T. Richards.04.

What I love about this painting:

I first featured this painting in June of 2020. This is one of my favorite seascapes, as it captures the cold sense of danger that is a storm at seashore. The waves crash against the rocks, and only a fool goes wading along this stretch of the beach.

But after the sea calms, the shore will be littered with rare unbroken shells and driftwood, a picker’s paradise.

William Trost Richards shows us a blustery day along the rugged coast of Cornwall. Intermittent rain squalls blow through, and when one passes the sun peeps out, the bright lull between storms. The sea is that dark greenish color reflecting the sky, a quality stormy waters here in the North Pacific coast often have. It is of a shore half a world away from me (in England), but it feels as familiar as if it were the coast of my home, Washington State.

What I love most about how Richards depicted the water is the milk-glass opaqueness of the green water and the way the light seems to shine through the waves. Luminist landscapes emphasize tranquility, and often depict calm, reflective water and a soft, hazy sky.

About the Artist via Wikipedia:

William Trost Richards rejected the romanticized and stylized approach of other Hudson River painters and instead insisted on meticulous factual renderings. His views of the White Mountains are almost photographic in their realism. In later years, Richards painted almost exclusively marine watercolors.

In the summer of 1874 Richards visited Newport, Rhode Island, and became enthralled with the area’s sublime coastline. He purchased his first of several Newport area homes in 1875 and continued to paint there for the rest of his life, dividing time between Newport and Chester County, Pennsylvania, where he purchased a farm near the Brandywine in 1884. Richards made many excursions to Europe, especially Britain and Ireland, where he produced an important body of work. [1]

Richards was one of the few 19th century American landscape artists who was equally skilled as a watercolorist and a painter in oils. His drawings are considered among the finest of his generation. Many of his drawing still survive.

Today, Richards is best known for his luminist seascapes. Paintings such as the one featured here today demonstrate his mastery of light and atmosphere. His favorite subjects were the Rhode Island, New Jersey and British coasts.

Credits and Attributions:

IMAGE: Off the Coast of Cornwall, by William Trost Richards Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:William Trost Richards – Off the Coast of Cornwall.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:William_Trost_Richards_-_Off_the_Coast_of_Cornwall.jpg&oldid=1127134702 (accessed January 8, 2026).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “William Trost Richards,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=William_Trost_Richards&oldid=1324003703 (accessed January 8, 2026).

Artist:

Artist:

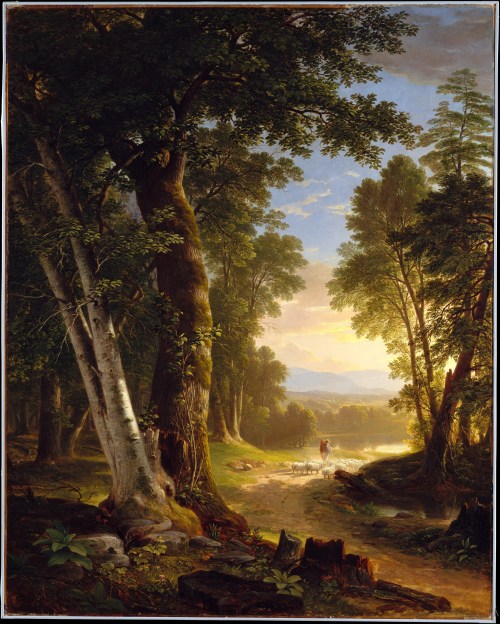

Title: Indian Summer by William Trost Richards

Title: Indian Summer by William Trost Richards

Artist: John Constable (1776–1837)

Artist: John Constable (1776–1837)

Artist:

Artist:  Artist: Thomas Cole (1801–1848)

Artist: Thomas Cole (1801–1848)