A reader’s perception of a narrative’s reality is affected by emotions they aren’t even aware of, an experience created by the layers of worldbuilding.

Mood and atmosphere are separate but entwined forces. They form subliminal impressions in the reader’s awareness, subcurrents that affect our personal emotions.

Mood and atmosphere are separate but entwined forces. They form subliminal impressions in the reader’s awareness, subcurrents that affect our personal emotions.

The emotions evoked in readers as they experience the story are created by the combination of mood, atmosphere, and subtext.

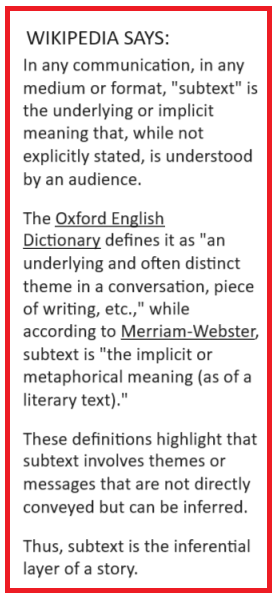

Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. It lies below the surface and supports the plot and the conversations. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning we deduce from the narrative. It’s conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. It lies below the surface and supports the plot and the conversations. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning we deduce from the narrative. It’s conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

Emotion is the experience of contrasts, of transitioning from the negative to the positive and back again. Mood, atmosphere, and emotion are part of the inferential layer of a story, part of the subtext. When an author has done their job well, the reader experiences the emotional transitions as the characters do. It is our job to make those transitions feel personal.

The atmosphere of a story is long-term. Atmosphere is the aspect of mood that is conveyed by the setting as well as the general emotional state of the characters.

The mood of a story is also long-term, but it is a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story.

Scene framing is the order in which we stage the people and the visual objects we include in a scene, as well as the sequence of scenes along the plot arc. It shapes the overall mood and atmosphere and contributes to the subtext. We choose the furnishings, sounds, and odors that are the visual necessities for that scene, and we place the scenes in a logical, sequential order.

We want to avoid excessive exposition, and good worldbuilding can help us with that. Let’s say we want to convey a general atmosphere of gloom and show our character’s mood without an info dump. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is key to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood.

We want to avoid excessive exposition, and good worldbuilding can help us with that. Let’s say we want to convey a general atmosphere of gloom and show our character’s mood without an info dump. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is key to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood.

Barren landscapes and low windswept hills feel cold and dark to me. The word gothic in a novel’s description tells me it will be a dark, moody piece set in a stark, desolate environment. A cold, barren landscape, constant dampness, and continually gray skies set a somber tone to the background of the scene.

A setting like that underscores each of the main characters’ personal problems and evokes a general atmosphere of gloom.

When we are designing the setting of a scene, which aspect of atmosphere is more important, mood or emotion? As I have said before, both and neither because they are entwined. Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group—the overall mood.

When we are designing the setting of a scene, which aspect of atmosphere is more important, mood or emotion? As I have said before, both and neither because they are entwined. Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group—the overall mood.

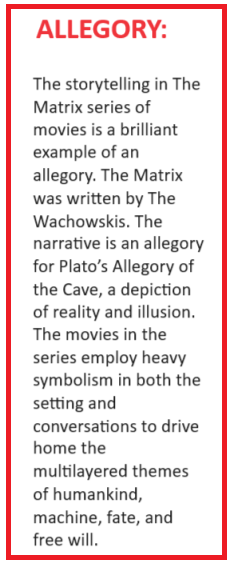

What tools in our writer’s toolbox are effective in conveying an atmosphere and a specific mood? Once we have chosen an underlying theme, it’s time to apply allegory and symbolism – two devices that are similar but different. The difference between them is how they are presented.

- Allegory is a moral lesson in the form of a story, heavy with symbolism.

- Symbolism is a literary device that uses one thing throughout the narrative (perhaps shadows) to represent something else (grief).

What are some examples? Cyberpunk, as a subgenre of science fiction, is exceedingly atmosphere-driven. It is heavily symbolic in worldbuilding and often allegorical in the narrative. We see many features of the classic 18th and 19th-century Sturm und Drang literary themes but set in a dystopian society. The deities that humankind must battle are technology and industry. Corporate uber-giants are the gods whose knowledge mere mortals desire and whom they seek to replace.

The setting and worldbuilding in cyberpunk work together to convey a gothic atmosphere, an overall feeling that is dark and disturbing. This is reflected in the subtext, which explores the dark nature of interpersonal relationships and the often criminal behaviors our characters engage in for survival.

No matter what genre we write in, we can use the setting to hint at what is to come. We can give clues by how we show the atmosphere with the inclusion of colors, scents, and ambient sounds. We choose our words carefully as they determine how the visuals are shown.

We can create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. We can lighten the mood as easily as we can darken it. When we design a setting, color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene.

We can create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. We can lighten the mood as easily as we can darken it. When we design a setting, color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene.

Sunshine, green foliage, blue skies, and birdsong go a long way toward lifting my spirits, so when I read a scene that is set in that kind of environment, the mood of the narrative feels lighter to me.

Worldbuilding can feel complicated when we are trying to convey subtext, mood, and atmosphere but the reader won’t be aware of the complexities. All they will know is how strongly the protagonist and her story affected them and how much they loved that novel.

Robert McKee tells us that emotion is the experience of transition, of the characters moving between a state of positivity and negativity.

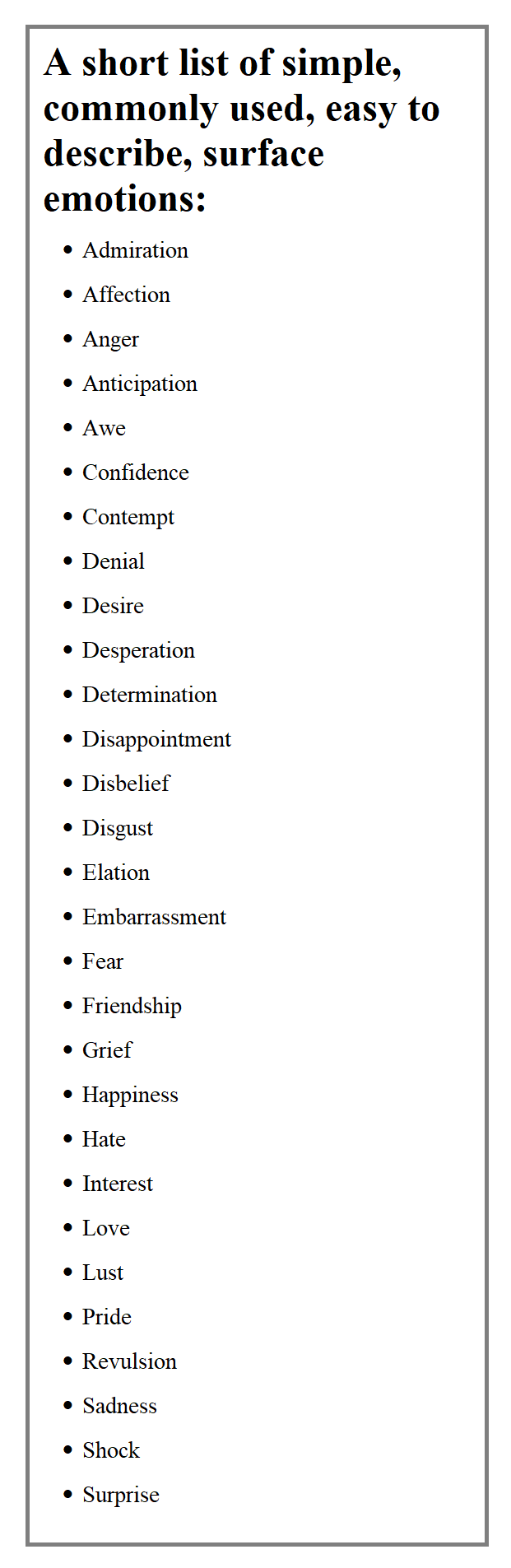

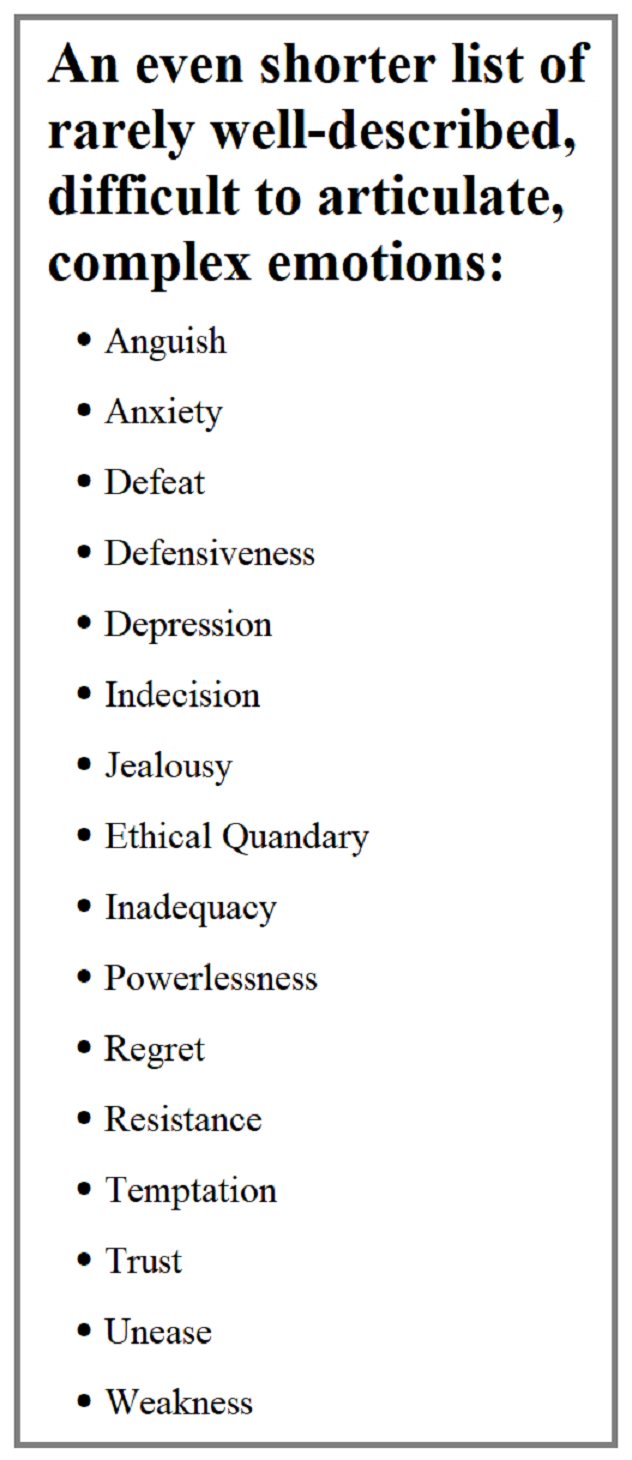

Robert McKee tells us that emotion is the experience of transition, of the characters moving between a state of positivity and negativity.  These visuals can easily be shown. Grief manifests in many ways and can become a thread running through the entire narrative. That theme of intense, subliminal emotion is the underlying mood and it shapes the story:

These visuals can easily be shown. Grief manifests in many ways and can become a thread running through the entire narrative. That theme of intense, subliminal emotion is the underlying mood and it shapes the story: This is part of the inferential layer, as the audience must infer (deduce) the experience. You can’t tell a reader how to feel. They must experience and understand (infer) what drives the character on a human level.

This is part of the inferential layer, as the audience must infer (deduce) the experience. You can’t tell a reader how to feel. They must experience and understand (infer) what drives the character on a human level. As we read, the atmosphere that is shown within the pages colors and intensifies our emotions, and at that point, they feel organic. Think about a genuinely gothic tale: the mood and atmosphere

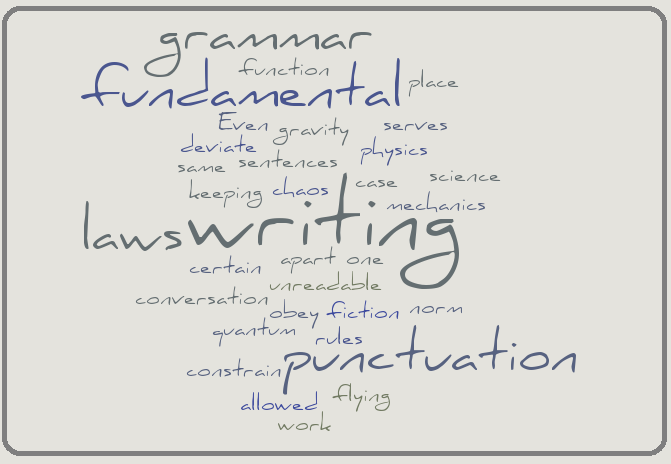

As we read, the atmosphere that is shown within the pages colors and intensifies our emotions, and at that point, they feel organic. Think about a genuinely gothic tale: the mood and atmosphere  In his book,

In his book,  Truthfully, I find detailed descriptions of facial expressions to be boring and sometimes off-putting. Every author armed with a little knowledge writes characters with curving lips, stretching lips, and lips doing many things over, and over, and over … with little variation.

Truthfully, I find detailed descriptions of facial expressions to be boring and sometimes off-putting. Every author armed with a little knowledge writes characters with curving lips, stretching lips, and lips doing many things over, and over, and over … with little variation. Simplicity has an impact, but I struggle to achieve balance. When looking for words with visceral and emotional power, consonants are your friend. Verbs that begin with consonants are powerful.

Simplicity has an impact, but I struggle to achieve balance. When looking for words with visceral and emotional power, consonants are your friend. Verbs that begin with consonants are powerful. Once the first draft is a complete novel, I will step away from it for a few weeks and work on other projects. Then when I come back to it, I use the global search (find option) to look for each instance of ‘ly’ words and rewrite those sentences to make them active.

Once the first draft is a complete novel, I will step away from it for a few weeks and work on other projects. Then when I come back to it, I use the global search (find option) to look for each instance of ‘ly’ words and rewrite those sentences to make them active. Synonyms for ominous that we could use: baleful, dire, direful, foreboding, ill, ill-boding, inauspicious, menacing, portentous, sinister, threatening.

Synonyms for ominous that we could use: baleful, dire, direful, foreboding, ill, ill-boding, inauspicious, menacing, portentous, sinister, threatening. If you are writing any kind of genre work, the best way to use your descriptors is to find the word that conveys the atmosphere you want with the most force. That word will help you visualize the scene and enable your ability to spew the story.

If you are writing any kind of genre work, the best way to use your descriptors is to find the word that conveys the atmosphere you want with the most force. That word will help you visualize the scene and enable your ability to spew the story.

![[[File:H. A. Brendekilde - Udslidt (1889).jpg|H. A. Brendekilde - Udslidt (1889)]]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/h._a._brendekilde_-_udslidt_1889.jpg?w=300)

![Lloyd Branson [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/berry-ellen-mcclung-by-branson.jpg?w=241)