I always think that in some ways, books are like machines. They’re comprised of many essential components, and if one element fails, the book won’t work the way the author envisions it.

Prose, plot, transitions, pacing, theme, characterization, dialogue, and mechanics (grammar/punctuation).

As an editor, I’ve seen every kind of mistake you can imagine, and I have written some travesties myself. I need my writing group, people with a critical eye who see my work first and give me good advice when I’ve gone astray.

I don’t want to waste my editor’s time, so once I have completed the revisions suggested by my beta readers, I begin a self-edit.

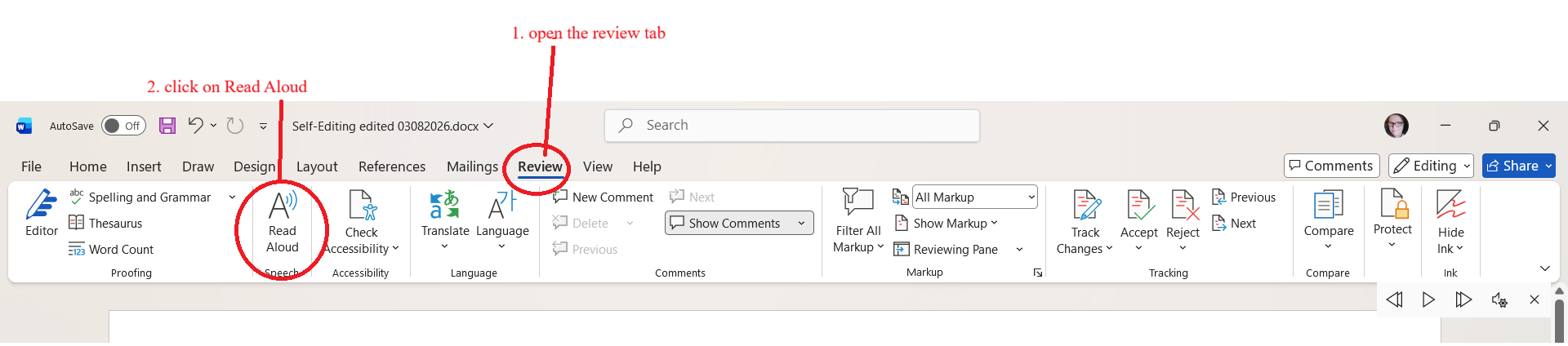

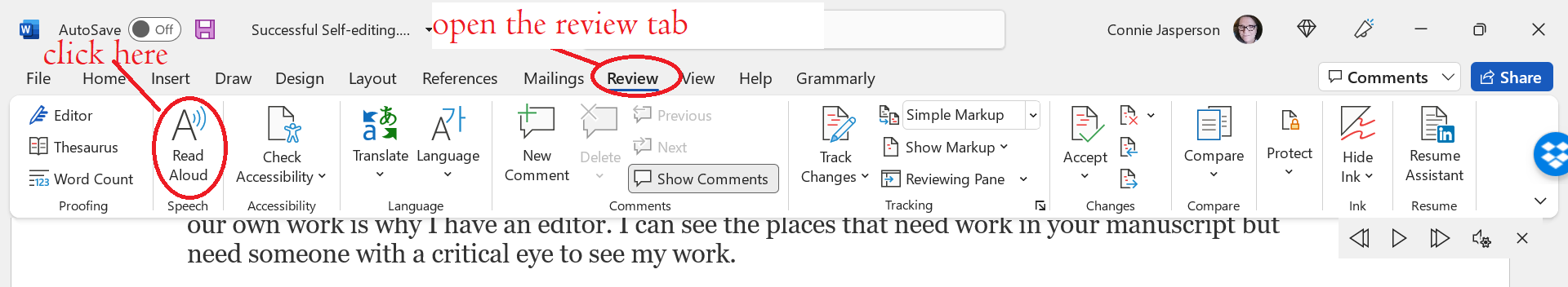

I use Microsoft Word, but most word processing programs have a read-aloud function. I place the cursor where I want to begin and open the Review Tab. Then, I click on Read Aloud and begin reading along with the mechanical voice. Yes, the AI voice can be annoying and doesn’t always pronounce things right, but this first tool shows me a wide variety of places that need rewriting.

I habitually type ‘though’ when I mean ‘through,’ and ‘lighting’ when I mean ‘lightning.’ These are two widely different words but are only one letter apart. Most misspelled words will leap out when you hear them read aloud.

I habitually type ‘though’ when I mean ‘through,’ and ‘lighting’ when I mean ‘lightning.’ These are two widely different words but are only one letter apart. Most misspelled words will leap out when you hear them read aloud.

- Run-on sentences stand out.

- Inadvertent repetitions also stand out.

- Hokey phrasing doesn’t sound as good as you thought it was.

- You notice where words like “the” or “a” before a noun were skipped.

This process involves a lot of stopping and starting, taking me a week to get through the entire 90,000-word manuscript. At the end, I will have trimmed about 3,000 words.

The next phase of this process is where I find and correct punctuation and find more places that need improvement. Sometimes I trim away entire sections, riffs on ideas that have already been presented. Often, they are outright repetitions that don’t leap out on the computer screen. (Those are often cut-and-paste errors.)

The next phase of this process is where I find and correct punctuation and find more places that need improvement. Sometimes I trim away entire sections, riffs on ideas that have already been presented. Often, they are outright repetitions that don’t leap out on the computer screen. (Those are often cut-and-paste errors.)

Open your manuscript. Break it into separate chapters, and make sure each is clearly and consistently labeled. Make certain the chapter numbers are in the proper sequence and that they don’t skip a number. For a work in progress, Baron’s Hollow, I would title the chapter files this way:

- BH_ch_1

- BH_ch_2

- and so on until the end.

Print out the first chapter. Everything looks different printed out, and you will see many things you don’t notice on the computer screen or hear when the AI voice reads it aloud.

- Turn to the last page. Cover the page with another sheet of paper, leaving only the last paragraph visible.

- Starting with the last paragraph on the last page, begin reading, working your way forward.

- Use a yellow highlighter to mark each place that needs correction.

- Put the corrected chapter on a recipe stand next to your computer. Open your document and begin making revisions as noted on your hard copy.

Repeat this process with each chapter.

This is the phase where I look for what I think of as code words. I look at words like “went.” In my personal writing habits, “went” is a code word that tells me when a scene ends and transitions to another stage. The characters or their circumstances are undergoing a change. One scene is ending, and another is beginning.

Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals that tell me what I intend the scene to be. In the rewrite, I must expand on those ideas and ensure the prose is active. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals that tell me what I intend the scene to be. In the rewrite, I must expand on those ideas and ensure the prose is active. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

Let’s look at the word “went.” When I see it, I immediately know someone is going somewhere.

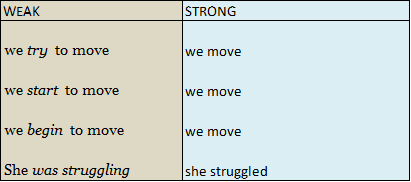

But in many contexts, “went” is a telling word and can lead to passive phrasing.

Passive phrasing does the job with little effort on the author’s part, which is why the first drafts of my work are littered with it. Active phrasing takes more effort because it involves visualizing a scene and showing it to the reader.

I ask myself, “How do they go?” Went can always be shown as a brief, one-sentence scene. James opened the door and strode out.

Confusing passages stand out when you see them printed. Maybe it’s the opposite of an info dump. Maybe the lead-up to the scene wasn’t shown well enough and leaves the reader wondering how such a thing happened.

The most confusing places are often sections where I cut a sentence or paragraph and moved it to a different place. These really stand out if they create a garbled scene.

HINT: If your eye wants to skip over a section of the printout, STOP. Read that section aloud and discover why your mind wants to skip it. Was it too wordy? Was it muddled? Something made your eye want to skip it and you need to discover why.

HINT: If your eye wants to skip over a section of the printout, STOP. Read that section aloud and discover why your mind wants to skip it. Was it too wordy? Was it muddled? Something made your eye want to skip it and you need to discover why.

By the end of phase two, I will have trimmed about 3,000 more words from my manuscript.

At this point, the manuscript might look finished, but it has only just begun the journey. Now it is as ready as I can make it, and it goes to my editor, Irene, who gives it the final polish.

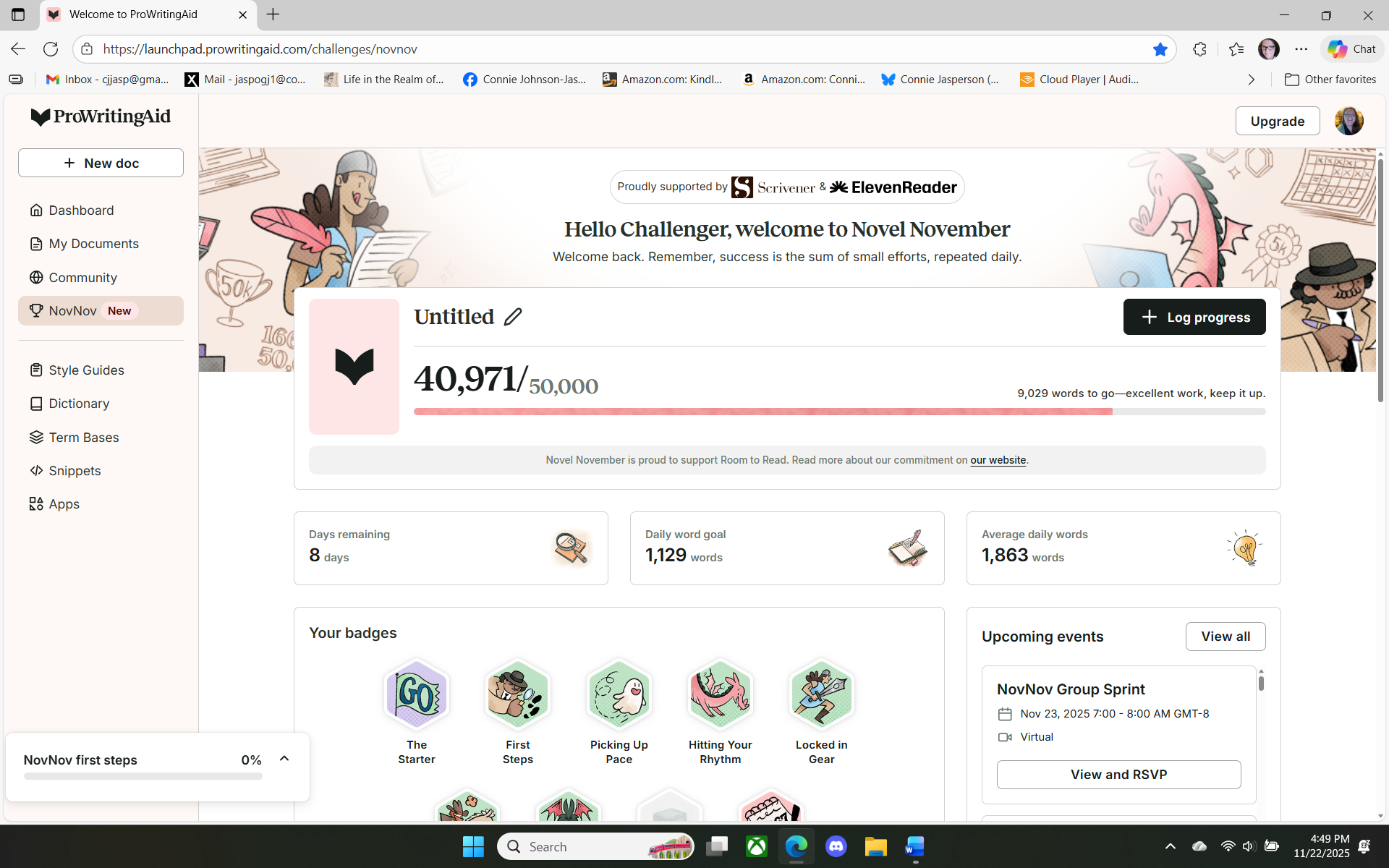

Context is everything. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible comma and spelling malfunctions.

If you don’t know anything about punctuation, don’t feel alone. Most of us don’t when we’re first starting out, but we learn by looking things up and practicing.

If you are looking for a simple guide to commas that will cost you nothing, check out my post, Fundamentals of Grammar: 7 basic rules of punctuation, published here July 7, 2021.

It follows that certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. Code words are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One word, one packet of letters will serve many purposes and convey a myriad of mental images.

It follows that certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. Code words are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One word, one packet of letters will serve many purposes and convey a myriad of mental images. I want to avoid that sin in my work, but what are my code words? What words are being inadvertently overused as descriptors? A good way to discover this is to make a word cloud. The words that see the most screen time will be the largest.

I want to avoid that sin in my work, but what are my code words? What words are being inadvertently overused as descriptors? A good way to discover this is to make a word cloud. The words that see the most screen time will be the largest.  endured

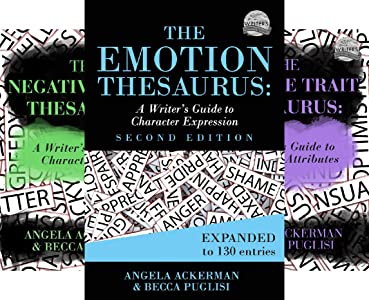

endured Sometimes, the only thing that works is the brief image of a smile. Nothing is more boring than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I want to know what is happening inside our characters and can be put off by an exaggerated outward display.

Sometimes, the only thing that works is the brief image of a smile. Nothing is more boring than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I want to know what is happening inside our characters and can be put off by an exaggerated outward display. If you don’t have it already, a book you might want to invest in is

If you don’t have it already, a book you might want to invest in is  NEVER DELETE months of work. Don’t trash what could be the seeds of another novel. Save it in an outtakes file and use it later. I give the subfile a name like HA_outtakes_20Dec2022. That file name tells me the cut chapters were last changed on December 20, 2022.

NEVER DELETE months of work. Don’t trash what could be the seeds of another novel. Save it in an outtakes file and use it later. I give the subfile a name like HA_outtakes_20Dec2022. That file name tells me the cut chapters were last changed on December 20, 2022. Then, I give the second draft a new file name: Heavens_Altar_version_2, which becomes the version I work on out of the main file folder.

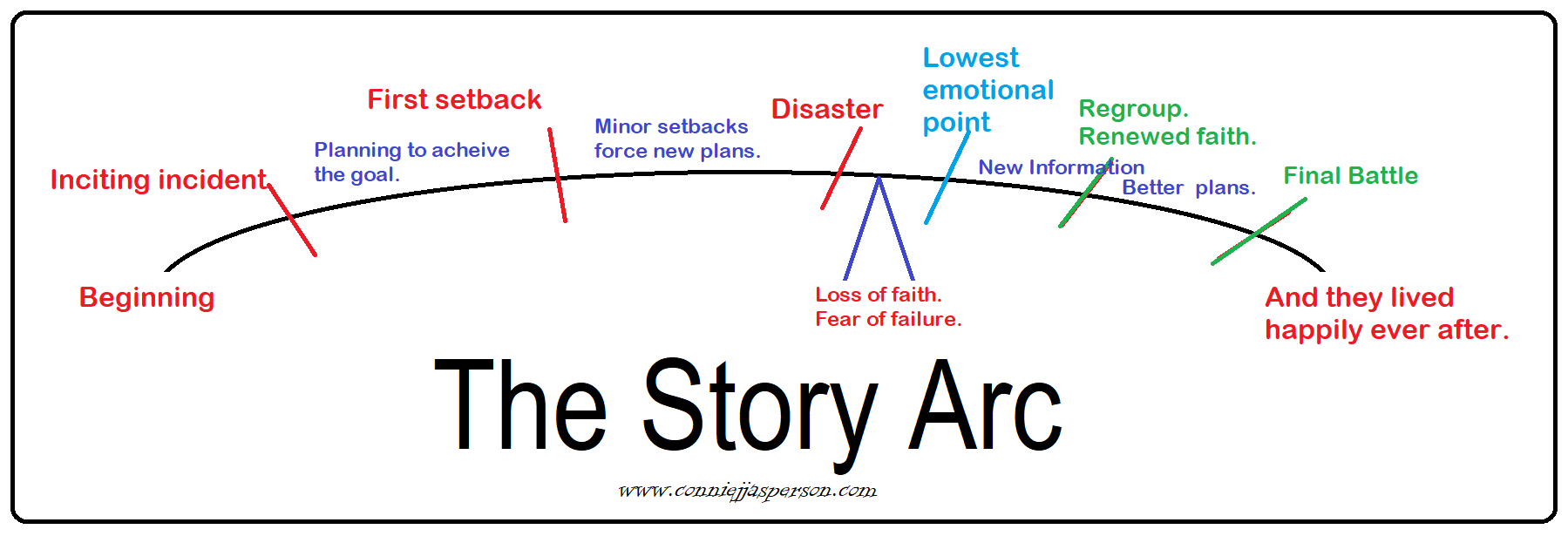

Then, I give the second draft a new file name: Heavens_Altar_version_2, which becomes the version I work on out of the main file folder. Either way, the characters will be profoundly changed from who they thought they were on page one, becoming who they are when the final sentence is written. The character arc is formed by their experiences.

Either way, the characters will be profoundly changed from who they thought they were on page one, becoming who they are when the final sentence is written. The character arc is formed by their experiences. True inspiration is not an everlasting firehose of ideas. Sometimes there are dry spells. If you take another look at the work you have cut and saved in an outtakes file, you might see it with fresh eyes. You might see the seeds of a different story, and the fire for writing will be reignited.

True inspiration is not an everlasting firehose of ideas. Sometimes there are dry spells. If you take another look at the work you have cut and saved in an outtakes file, you might see it with fresh eyes. You might see the seeds of a different story, and the fire for writing will be reignited. We add the details when we begin the revision process. One of the elements we look for in our narrative is pacing, or how the story flows from the opening scene to the final pages.

We add the details when we begin the revision process. One of the elements we look for in our narrative is pacing, or how the story flows from the opening scene to the final pages. This string of scenes is like the ocean. It has a kind of rhythm, a wave action we call pacing. Pacing is created by the way an author links actions and events, stitching them together with quieter scenes: transitions.

This string of scenes is like the ocean. It has a kind of rhythm, a wave action we call pacing. Pacing is created by the way an author links actions and events, stitching them together with quieter scenes: transitions.

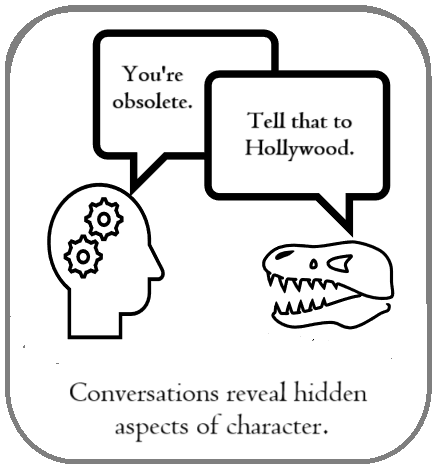

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals. With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals. With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.

In some ways, novels are machines. Internally, each book is comprised of many essential components. If one element fails, the story won’t work the way I envision it.

In some ways, novels are machines. Internally, each book is comprised of many essential components. If one element fails, the story won’t work the way I envision it. So, realizing I knew nothing was the first positive thing I did for myself. I made it my business to learn all I could, even though I will never achieve perfection.

So, realizing I knew nothing was the first positive thing I did for myself. I made it my business to learn all I could, even though I will never achieve perfection. I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is.

I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is. This is a long process that involves a lot of stopping and starting, taking me a week to get through an entire 90,000-word manuscript. I will have trimmed about 3,000 words by the end of phase one. I will have caught many typos and miskeyed words and rewritten many clumsy sentences.

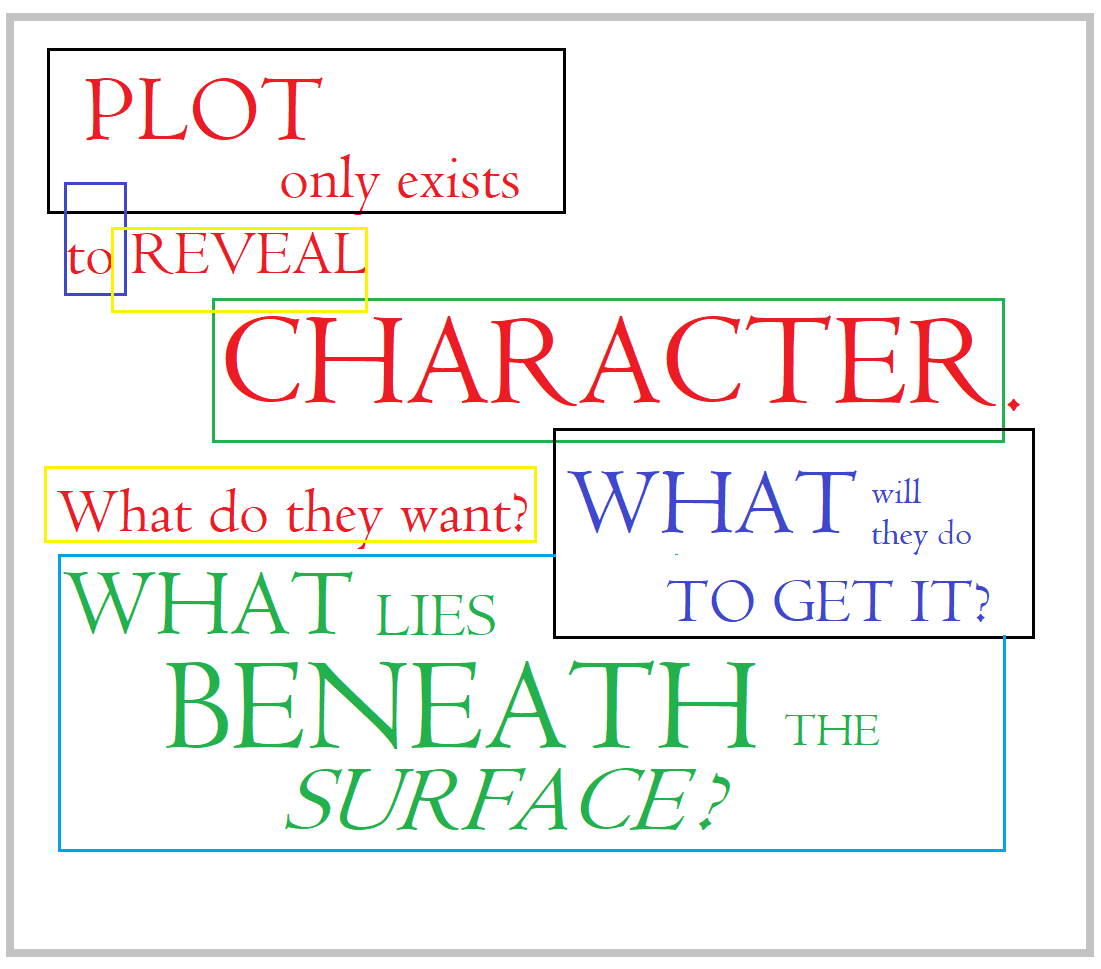

This is a long process that involves a lot of stopping and starting, taking me a week to get through an entire 90,000-word manuscript. I will have trimmed about 3,000 words by the end of phase one. I will have caught many typos and miskeyed words and rewritten many clumsy sentences. This is the phase where I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. These telling passages are codes for the author, laid down in the first draft. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

This is the phase where I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. These telling passages are codes for the author, laid down in the first draft. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination. Editing programs operate on algorithms and don’t understand context. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess.

Editing programs operate on algorithms and don’t understand context. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess. Now you must set it aside, as you must gain a little distance from it to see it with a clear eye. This is where I seek an outside opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of my proto-novel. I am fortunate to have a local writing group of highly talented published authors. I also trade services with several editors. When the first draft of my manuscript is finished, I send it to a reader. While they are reading it, I work on something completely different.

Now you must set it aside, as you must gain a little distance from it to see it with a clear eye. This is where I seek an outside opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of my proto-novel. I am fortunate to have a local writing group of highly talented published authors. I also trade services with several editors. When the first draft of my manuscript is finished, I send it to a reader. While they are reading it, I work on something completely different. In my current work, the thoughts and motives of the characters are critical to the midpoint event and subsequent crisis of faith. Yes, who these people are, and their place in the story at the point where we meet them is crucial to the plot.

In my current work, the thoughts and motives of the characters are critical to the midpoint event and subsequent crisis of faith. Yes, who these people are, and their place in the story at the point where we meet them is crucial to the plot.