We have just finished the first six parts in our story creation series. We talked about developing characters and allowing them to help us plot our story, and the links to those posts are down below. Now, we’re going to let our characters show us the environment and landscape of their world.

First, even though the sample plot we’ve been working with is for a pseudo-medieval fantasy, you don’t have to write in that genre to benefit from listening to your characters. Our characters will tell us what their world looks like, no matter what genre we set it in.

First, even though the sample plot we’ve been working with is for a pseudo-medieval fantasy, you don’t have to write in that genre to benefit from listening to your characters. Our characters will tell us what their world looks like, no matter what genre we set it in.

The plot of our sample story as it evolved over the last six weeks tells us it will be set in several places: a castle fortress, a manor house, a cottage in an as-yet-nameless village, and a hut in a forest.

One problem I have noticed as an avid reader is the tendency to build contradictions into the geography of our world. It happens as we lay the story down on paper, expanding scenes and interactions. One of my favorite authors is consistently guilty of this despite having published more than eighty novels.

We don’t want to build flaws into our narrative, but we all want to speed up the process of finishing the first draft.

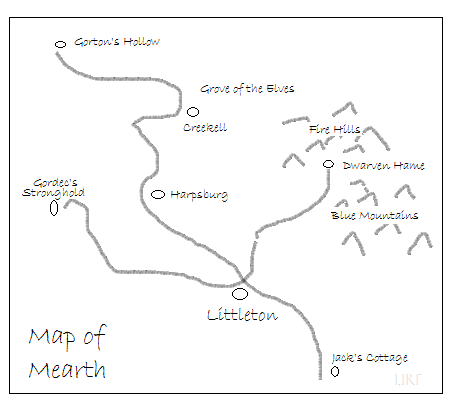

I find a small, hand-scribbled map is the best way to do this. I begin with the opening location, and each time the group goes somewhere, I add it to my map. That way, I have them going in the right direction consistently, and it takes the same length of time to get there each time they must make the journey.

I find a small, hand-scribbled map is the best way to do this. I begin with the opening location, and each time the group goes somewhere, I add it to my map. That way, I have them going in the right direction consistently, and it takes the same length of time to get there each time they must make the journey.

All we need is some idea of directions and distances, an idea of how long it takes to travel using the standard mode of transportation.

In my own writing, I keep the visuals simple, basing the plants and topography on the Pacific Northwest, where I live. It’s a lot less work to write what we are familiar with when it comes to flora and fauna, as well as mountains and seas.

When Val looks out the window, she sees a hilly country covered in a forest of firs and cedar trees interspersed with clearings. Wherever a giant tree has fallen, sunlight creates places where ash, maples, and cottonwoods find fertile soil. In turn, those trees offer shelter to the young seedlings of the fir and cedars, ensuring that the forest continues its cycle of life.

When Val and Kai move their troops for the final battle, they must travel over hills and valleys and cross rivers. They must know where the villages that are sympathetic to them are and avoid those controlled by the enemy.

- As the rough draft evolves, sometimes towns must be renamed or may have to be moved to more logical places.

- Whole mountain ranges may have to be moved or reshaped so our characters encounter forests and savannas where they are supposed to be in the story.

The topography isn’t the only thing Guard Captain Val must contend with from day one. It’s a fantasy so there may be rare beasts to deal with.

The topography isn’t the only thing Guard Captain Val must contend with from day one. It’s a fantasy so there may be rare beasts to deal with.

Also, when we decided she was captain of the royal guard and co-regent for young King Edward, we implied a Renaissance level of technology. This means they are pre-industrial, relying on horses, mules, and oxen for personal transportation and transporting goods. Thus, wagons, carts, and carriages will provide transportation when one doesn’t want to ride horseback or must transport large quantities of goods.

We will go into how available technology affects what our characters can do later in this series.

Any story set in prehistorical times is a fantasy, as the author must imagine social interactions and environments based on the information available in the archeological record.

- Historical eras are those where written records have been archived and passed down to us.

- Any story set in a society without written records is a fantasy–no matter what genre you label it with. Although mythology, conjecture, and theorizing abound, few scientific facts exist until an archeological expedition can investigate any artifacts and ruins they left behind. And even then, there will be a certain literary license to the archaeologist’s conclusions.

If you are setting your novel in a real-world city as it currently exists, make good use of Google Earth. Bookmark it now, even if you live in that town, as the maps you will generate will help you stay on track.

If you are setting your novel in a real-world city as it currently exists, make good use of Google Earth. Bookmark it now, even if you live in that town, as the maps you will generate will help you stay on track.

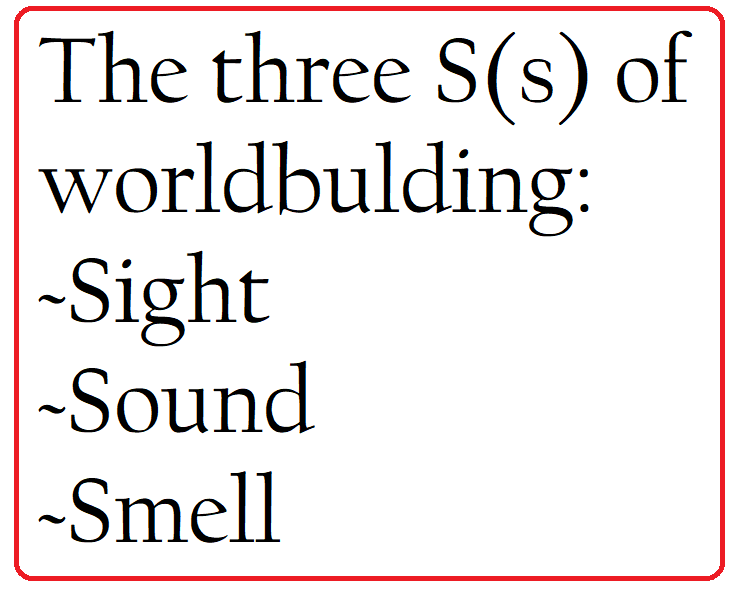

Our characters will reveal the sights, sounds, and scents of their world to us. They will tell us if they feel at home in the forest, as Val does. Or they will indicate unease and fear, as Kai does when he is thrown into an environment he has never experienced.

The metallic aftertaste of terror overrode the musty scents of damp earth and rotting leaves. The rank odor of startled skunk lingered, but the occasional calls of small forest creatures went on around him as if everything were normal. It wasn’t, but hell would freeze before he admitted it. As cold as it was, it probably had.

When it comes to geography, the “three S’s” of world-building are critical: sights, sounds, and smells. Those sensory elements create what we know of the world. What does your character see, hear, and smell? Taste rarely comes into it except when showing an odor or emotion.

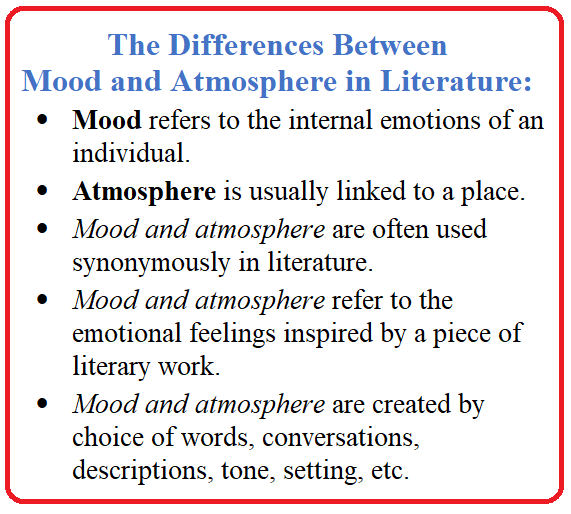

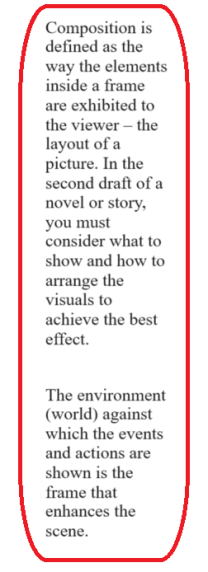

Scene framing is an aspect of world-building. It is the order in which we stage our characters and the visual objects they interact with. It shapes the overall mood and atmosphere of a scene.

The atmosphere of a narrative is a long-term feature of the story, winding through and evolving over the length of the piece. Atmosphere is conveyed by the setting as well as the general emotional state of the characters.

The atmosphere of a narrative is a long-term feature of the story, winding through and evolving over the length of the piece. Atmosphere is conveyed by the setting as well as the general emotional state of the characters.

The mood of a story is also long-term, but it is a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed—subliminal. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story.

Once we have our characters in place, they will show us the furnishings, sounds, and odors that are the visual necessities for that scene. All we have to do is let them do their jobs.

In the first draft, our primary task is to get the bare bones of the settings down. We must write the story as it falls from our imaginations first. For example, I won’t worry about the details of that gorgeous tapestry hanging in King Edward’s bedroom. I’ll just write the scene where Donovan kidnaps him. If the tapestry becomes important later, we’ll have a closer look at it.

World-building gets expanded on or trimmed back during the revision process. It is an aspect of writing that continues through every draft of the manuscript. Beta readers will mention aspects of the world that need attention, and even in the editing process some adjustments will be made.

World-building gets expanded on or trimmed back during the revision process. It is an aspect of writing that continues through every draft of the manuscript. Beta readers will mention aspects of the world that need attention, and even in the editing process some adjustments will be made.

Next week, we’ll look at the different levels of society that shaped our two main characters. We will see how their most cherished biases were formed, and with that understanding, we will understand how and why the whole debacle that is our story began.

PREVIOUS IN THIS SERIES:

Idea to story part 2: thinking out loud #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 3: plotting out loud #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 4 – the roles of side characters #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 5 – plotting treason #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Idea to story part 6 – Plotting the End #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy

Directors will tell you they focus the scenery (set dressing) so it frames the action. The composition of props in that scene is finely focused world-building, and it draws the viewer’s attention to the subtext the director wants to convey.

Directors will tell you they focus the scenery (set dressing) so it frames the action. The composition of props in that scene is finely focused world-building, and it draws the viewer’s attention to the subtext the director wants to convey. As I work my way through revisions, I struggle to find the right set dressing to underscore the drama. Each item mentioned in the scene must emphasize the characters’ moods and the overall atmosphere of that part of the story.

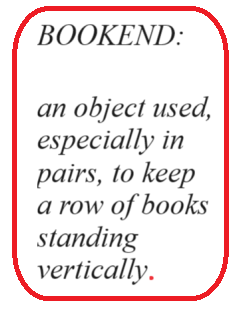

As I work my way through revisions, I struggle to find the right set dressing to underscore the drama. Each item mentioned in the scene must emphasize the characters’ moods and the overall atmosphere of that part of the story. We can bookend the event with “doorway” scenes. These scenes determine the narrative’s pacing, which is created by the rise and fall of action.

We can bookend the event with “doorway” scenes. These scenes determine the narrative’s pacing, which is created by the rise and fall of action. The opening paragraph of a chapter and the ending paragraph are miniature scenes that bookend the central action scene. They are doors that lead us into the event and guide us on to the next hurdle the character must overcome.

The opening paragraph of a chapter and the ending paragraph are miniature scenes that bookend the central action scene. They are doors that lead us into the event and guide us on to the next hurdle the character must overcome. When the next chapter opens, he steps into an opening paragraph that leads into the next action sequence. We find out who and what new misery is waiting for him on the other side of that door.

When the next chapter opens, he steps into an opening paragraph that leads into the next action sequence. We find out who and what new misery is waiting for him on the other side of that door. When you begin making revisions, take a look at the opening paragraph of each chapter. Ask yourself how it could be rewritten to convey information and lead the reader into the action. Then, look at the final paragraph and ask yourself the same question.

When you begin making revisions, take a look at the opening paragraph of each chapter. Ask yourself how it could be rewritten to convey information and lead the reader into the action. Then, look at the final paragraph and ask yourself the same question. In a novel or story, each scene occurs within the framework of the environment.

In a novel or story, each scene occurs within the framework of the environment. The Dragonriders of Pern series is considered science fiction because McCaffrey made clear at the outset that the star (Rukbat) and its planetary system had been colonized two millennia before, and the protagonists were their descendants.

The Dragonriders of Pern series is considered science fiction because McCaffrey made clear at the outset that the star (Rukbat) and its planetary system had been colonized two millennia before, and the protagonists were their descendants. The scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them. In both settings, the surroundings do the dramatic heavy lifting. This chapter is filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted.

The scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them. In both settings, the surroundings do the dramatic heavy lifting. This chapter is filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted. Sallah enters the shuttle just as the airlock door closes, catching and crushing her heel. She manages to pull it out so that she isn’t trapped, but she is severely injured.

Sallah enters the shuttle just as the airlock door closes, catching and crushing her heel. She manages to pull it out so that she isn’t trapped, but she is severely injured. This is an incredibly emotional scene: we are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her last breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground.

This is an incredibly emotional scene: we are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her last breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground. Each chapter is comprised of one or more scenes. These scenes have an arc to them: action and reaction. These arcs of action and reaction begin at point A and end at point B. Each launching point will land on a slightly higher point of the story arc.

Each chapter is comprised of one or more scenes. These scenes have an arc to them: action and reaction. These arcs of action and reaction begin at point A and end at point B. Each launching point will land on a slightly higher point of the story arc. he scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them: first the planet and then the abandoned colony ship, Yokohama. These scenes are filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted. Not all the drama is in Sallah Telgar’s direct interaction with Avril Bitra. The environment heightens the drama, the sense of impending doom.

he scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them: first the planet and then the abandoned colony ship, Yokohama. These scenes are filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted. Not all the drama is in Sallah Telgar’s direct interaction with Avril Bitra. The environment heightens the drama, the sense of impending doom. We see Avril taunting Sallah for her matronly body and move out again to see Avril tying a cord to Sallah’s crushed foot and forcing her to make the navigational calculations for Avril’s escape. We move close up and hear the interaction, Sallah pretending to do as Avril asks but really setting her enemy’s doom in action. The camera moves to the wide view again, and we hear the interaction with her frantic husband on the ground. We are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her dying breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground.

We see Avril taunting Sallah for her matronly body and move out again to see Avril tying a cord to Sallah’s crushed foot and forcing her to make the navigational calculations for Avril’s escape. We move close up and hear the interaction, Sallah pretending to do as Avril asks but really setting her enemy’s doom in action. The camera moves to the wide view again, and we hear the interaction with her frantic husband on the ground. We are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her dying breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground.