I plot my stories in advance, but once I begin writing, the characters sometimes take over. The plot veers far from what I had intended when I began writing it. Each time that happens, the code words we use to tell the story find their way into my manuscript, marking the places I need to revisit and rewrite to show the action. (See last week’s post, The Second Draft: Decoding My Mental Shorthand #writing | Life in the Realm of Fantasy (conniejjasperson.com).

This happens because my characters have agency and sometimes run amok. Thus, in the second draft, I examine the freedom I give my characters to introduce their own actions and reactions within the story.

This happens because my characters have agency and sometimes run amok. Thus, in the second draft, I examine the freedom I give my characters to introduce their own actions and reactions within the story.

Usually, the ending remains the same as proposed, no matter what the characters do. However, the path to that place can diverge, making the middle quite different from what was initially intended.

This is called giving your characters “agency.” Agency is an integral aspect of the creative process. It allows the written characters to become real, the way Pinocchio wanted to be a real boy and not a puppet.

I want their uniqueness to remain central to the story, even when their motives and actions diverge from the original plot outline.

In literary terms, “agency” is the ability of a character to surprise the author and, ultimately, the reader. If you plan every action and response when you are writing them, the experience of writing might feel canned and boring.

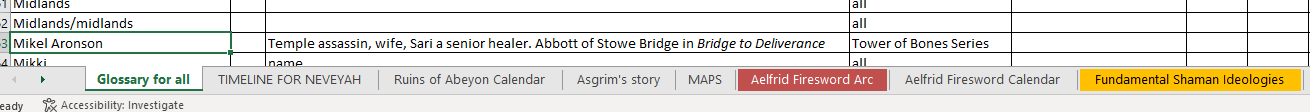

Plotting, for me, means setting out an arc of events for a story that I hope to write. I do this in advance, creating it in the form of a list in a new Excel workbook that is the bible for that universe. My outline workbook will contain several spreadsheets. On one page, I create the characters and give them personality traits. On another, I list the order of events that I think will form the arc of the story. Another page will have a glossary of words and names that are unique to that story. There will be maps and calendars to help keep things logical.

Some authors use whiteboards and sticky notes, and still others use Scrivener—a program my style of thinking doesn’t mesh with. Google Sheets works well, too, and it’s free. The way you plot your stories is up to you.

When my characters begin doing things that weren’t planned, the outline evolves. That way, I don’t lose control of the plot and go off on a side quest to nowhere. That is when I get to know my characters as people.

When the writing commences, the characters make choices and say things that surprise me. They can do this because I allow them agency.

When the writing commences, the characters make choices and say things that surprise me. They can do this because I allow them agency.

Each character will be left with several consequential choices to make in every situation that arises along the timeline. I consider the personality and allow the characters’ reactions to fit who they are.

No matter how they respond, they will be placed in situations where they have no choice but to go forward. After all, I am their creator, the deity of their universe. I have an outline that predestines them to specific fates, and nothing they can do will stop that train.

The consequences my characters face for their choices affect the atmosphere and mood of the story as it emerges. Think about it—if there are no consequences for a character’s bad decisions, everyone goes home unscathed. What sort of story is that? Why bother writing at all?

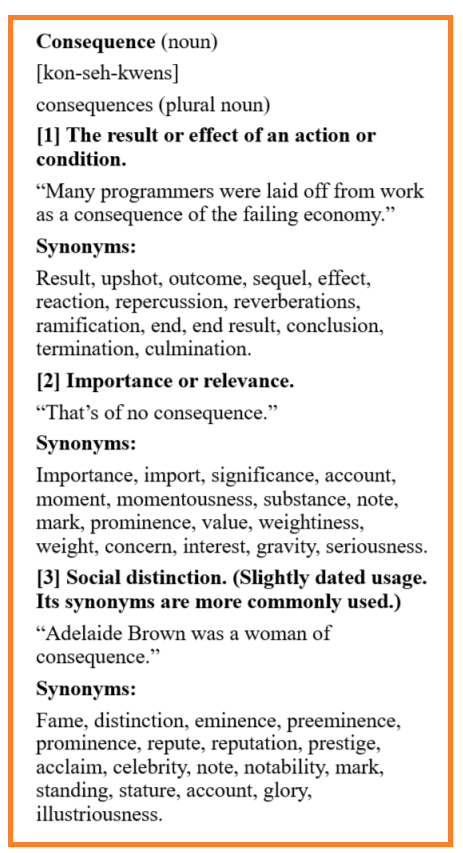

Let’s look at both the meanings and synonyms for the word consequences.

So now, let’s consider agency and the importance of choice. How will the consequences of their decisions affect our characters’ lives? After all, a story isn’t interesting without a few self-inflicted complications.

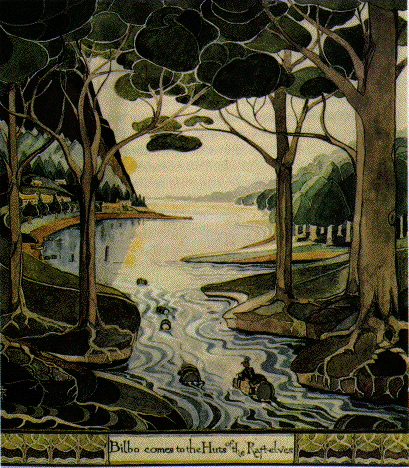

A story most fantasy authors are familiar with is J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Let’s have a closer look at Bilbo’s choices and his path to becoming the eccentric, eleventy-one-year-old hobbit who vanishes (literally), leaving everything, including the One Ring, to Frodo.

In the morning, after the unexpected (and unwanted) guests leave, he has two choices. He can stay in the safety of Bag End or hare off on a journey into the unknown. He chooses to run after the dwarves, and so begins the story of how a respectable hobbit embarked on a new career as a burglar and became a hero in the process.

Bilbo comes to the huts of the raft elves by J.R.R. Tolkien

The consequences of Bilbo’s decision will shape his entire life afterward. Where he was once a staid country squire, the pillar of respectability who had inherited a comfortable income and existence, he is now expected to steal an important treasure from a dragon.

At the outset, that particular job doesn’t seem real, and he can’t imagine doing it. More immediate problems beset him. First of all, he has no clue about how a successful burglar works. He knows better than anyone that he is completely unfit for the task.

Second, he’s always been well-fed, highly respected, and not inclined to physical labor. Now, he is a novice on the expedition, so his opinions carry no weight. Not only that, meals are scant by his standards, and they must do way too much walking.

Bilbo’s long-suppressed desire for adventure emerges early when the company encounters a group of trolls. He is supposed to be a thief, so he is sent to investigate a strange fire in a forest. Reluctantly, he agrees. Upon reaching the blaze, he observes that it is a cookfire for a group of trolls.

Bilbo must make a choice. The smart thing would be to turn around at that point and warn the dwarves that they are in mortal danger. However, Bilbo’s bruised ego takes over, and he chooses to do something to prove his worth.

“He was very much alarmed as well as disgusted; he wished himself a hundred miles away—yet somehow he could not go straight back to Thorin and Company empty-handed.” [1]

Bilbo’s desire to impress the Dwarves causes him to make regrettable decisions. His choice leads to everyone nearly getting eaten, which is a negative consequence.

Fortunately, they are rescued by Gandalf. While he is hiding, Bilbo discovers several historically important weapons. One of them is Sting, a blade that fits Bilbo perfectly as a sword. This is a positive consequence, as the blade is crucial to Bilbo’s story and later to Frodo’s story.

Fortunately, they are rescued by Gandalf. While he is hiding, Bilbo discovers several historically important weapons. One of them is Sting, a blade that fits Bilbo perfectly as a sword. This is a positive consequence, as the blade is crucial to Bilbo’s story and later to Frodo’s story.

It does not acquire its name until later in the adventure, after Bilbo, lost in the forest of Mirkwood, uses it to kill a giant spider and rescue the Dwarves. This is when Bilbo’s decisions become more thoughtful, and his courageous side begins to emerge.

Choices and consequences, both negative and positive, shape Bilbo’s character.

Sometimes, the decisions our characters make as we write surprise us. But if those choices make the story too easy, they should be discarded.

The best, most exciting moments I’ve had as an author are when my characters surprise me and take over the story. I can’t describe the feeling of exultation I experience when my characters choose to take the story in a different, much better direction than I had planned.

Ultimately, they end at the place I intended for them at the outset, but they always do it their own way and with their own style.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Quote from The Hobbit, or There and Back Again, by J.R.R. Tolkien, published 1937 by George Allen & Unwin, Ltd.