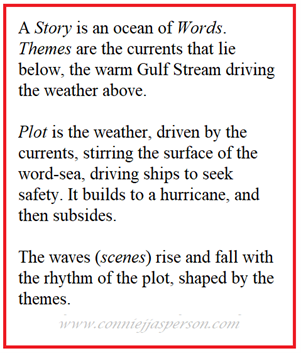

When I sit down to write a scene, my mind sees it as if through a camera, as if my narrative were a movie. The character and their actions are framed by the setting and environment. In so many ways, a writer’s imagination is like a camera, and as they write that first draft, the narrative unfolds like a movie.

Directors will tell you they focus the scenery (set dressing) so it frames the action. The composition of props in that scene is finely focused world-building, and it draws the viewer’s attention to the subtext the director wants to convey.

Directors will tell you they focus the scenery (set dressing) so it frames the action. The composition of props in that scene is finely focused world-building, and it draws the viewer’s attention to the subtext the director wants to convey.

Subtext is what lies below the surface. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning that shapes the narrative. It’s conveyed by the composition of the images we place in the environment and how they affect our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

As I work my way through revisions, I struggle to find the right set dressing to underscore the drama. Each item mentioned in the scene must emphasize the characters’ moods and the overall atmosphere of that part of the story.

As I work my way through revisions, I struggle to find the right set dressing to underscore the drama. Each item mentioned in the scene must emphasize the characters’ moods and the overall atmosphere of that part of the story.

Subtext supports the dialogue and gives purpose to the personal events. What furnishings, sounds, and odors are the visual necessities to support that scene? How can I best frame the interactions so that the most information is conveyed with the fewest words? And how do we chain our scenes together to create a smooth flow to our narrative?

We all struggle with transitions, and one helpful tool is this: we can bookend our scenes. But how does bookending work?

Last week, we talked about transitions and how they affect pacing, but we didn’t have time to expand on the mechanics. We want the events to unfold naturally so the plot flows logically.

Perhaps we have the plot all laid out in the right order. We know what must happen in this event so that the next event makes sense. But how do we move from this event to the next in such a way that the reader doesn’t notice the transitions?

We can bookend the event with “doorway” scenes. These scenes determine the narrative’s pacing, which is created by the rise and fall of action.

We can bookend the event with “doorway” scenes. These scenes determine the narrative’s pacing, which is created by the rise and fall of action.

Pacing consists of doing and showing linked together with a little telling. An example of an opening paragraph (from a short story) that conveys visual information is this:

Olin Erikson gazed at the remains of his barn. He turned back to Aeril, his nine-year-old son. “I know you didn’t shake our barn down intentionally, but it happened. I sense that you have a strong earth-gift, and you’ve been trying to hide it.”

In that particular short story, the opening paragraph consists of 44 words. It introduces the characters and tells you they have the ability to use magic. It also introduces the inciting incident. But bookends come in pairs, so what does a final paragraph do?

Another example is one I have used before. This next scene is the last paragraph of an opening chapter. Page one of the narrative opens with a short paragraph introducing the character—the hook. This is followed by a confrontation scene that introduces the inciting incident. Finally, we need to keep the reader hooked. The paragraph that follows here is the final paragraph of that introductory chapter:

I picked up my kit and looked around. No wife to kiss goodbye, no real home to leave behind, nothing of value to pack. Only the need to bid Aeoven and my failures goodbye. The quiet snick of the door closing behind me sounded like deliverance. I’d hit bottom, so things could only get better. Right?

While that particular narrative is told from the first-person point of view, any POV would work.

The opening paragraph of a chapter and the ending paragraph are miniature scenes that bookend the central action scene. They are doors that lead us into the event and guide us on to the next hurdle the character must overcome.

The opening paragraph of a chapter and the ending paragraph are miniature scenes that bookend the central action scene. They are doors that lead us into the event and guide us on to the next hurdle the character must overcome.

The objects my protagonists observe in each mini-scene allow the reader to infer a great deal of information about them and their actions. This is world-building and is crucial to how the reader visualizes the events.

Transition scenes are your opportunity to convey a lot of information with only a few words.

The character in the above transition scene performs an action and moves on to the next event. It reveals his mood and some of his history in 56 words of free indirect speech and propels him into the next chapter.

He does something: I picked up my kit and looked around. He performs an action in only 8 words, and that action gives us a great deal of information. It tells us that he is preparing to leave on an extended journey.

He shows us something: No wife to kiss goodbye, no real home to leave behind, nothing of value to pack. Only the need to bid Aeoven and my failures goodbye. In 26 words, he shows us a barren existence and offers us his self-evaluation as a failure.

He tells us something: The quiet snick of the door closing behind me sounded like deliverance. I’d hit bottom, so things could only get better. Right? 22 words show us his state of mind. The door has closed on an episode in his life, and he has no intention of going back.

This paragraph ends the chapter.

When the next chapter opens, he steps into an opening paragraph that leads into the next action sequence. We find out who and what new misery is waiting for him on the other side of that door.

When the next chapter opens, he steps into an opening paragraph that leads into the next action sequence. We find out who and what new misery is waiting for him on the other side of that door.

Small bookend scenes should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They don’t take up a lot of space, and they lay the groundwork for what comes next, subtly moving us forward.

One way to ensure the events of your story occur in a plausible way is to open a new document and list the sequence of events in the order in which they have to happen. That way, you can view the story as a whole and move events forward or back along the timeline to ensure a logical sequence.

The brief transition scene does the heavy lifting when it comes to conveying information. It is the best opportunity for clues about the characters and their history to emerge without an info dump.

A “thinking scene” opens a window for the reader to see how the characters see themselves.

When you begin making revisions, take a look at the opening paragraph of each chapter. Ask yourself how it could be rewritten to convey information and lead the reader into the action. Then, look at the final paragraph and ask yourself the same question.

When you begin making revisions, take a look at the opening paragraph of each chapter. Ask yourself how it could be rewritten to convey information and lead the reader into the action. Then, look at the final paragraph and ask yourself the same question.

Finding the right words to hook a reader, land them, and keep them hooked is a lot of work, but it will be worth it.

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

Our bookend scenes are not empty words. They should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They lay the groundwork for what comes next.

Our bookend scenes are not empty words. They should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They lay the groundwork for what comes next. One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, keeping each character thread separate and flowing well. A hard scene break with a new chapter is my preferred way to end a nice, satisfying fade-to-black.

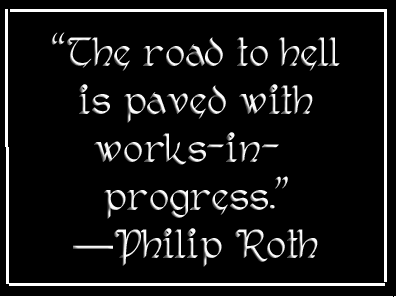

One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, keeping each character thread separate and flowing well. A hard scene break with a new chapter is my preferred way to end a nice, satisfying fade-to-black. The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next.

The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next. When we commit to writing daily, our writing style grows and changes. When I began writing, some chapters totaled over 4,000 words.

When we commit to writing daily, our writing style grows and changes. When I began writing, some chapters totaled over 4,000 words. As a reader, books work best for me when each chapter details the events of one large scene or several related events. I think of chapters as if they were paragraphs. Paragraphs are not just short blocks of randomly assembled sentences.

As a reader, books work best for me when each chapter details the events of one large scene or several related events. I think of chapters as if they were paragraphs. Paragraphs are not just short blocks of randomly assembled sentences. I’ve mentioned before that one of the complaints some readers have with

I’ve mentioned before that one of the complaints some readers have with  Short stories run up to 7,000 words, with under 4,000 being the most commonly requested length. 7,500–17,500 is the expected length for novelettes, and between 17,500 and 40,000 words are the standard length for novellas.

Short stories run up to 7,000 words, with under 4,000 being the most commonly requested length. 7,500–17,500 is the expected length for novelettes, and between 17,500 and 40,000 words are the standard length for novellas. In my work, the first draft is really more of an expanded outline, a series of scenes that have characters doing things. But those scenes need to be connected so each flows naturally into the next without jarring the reader out of the narrative.

In my work, the first draft is really more of an expanded outline, a series of scenes that have characters doing things. But those scenes need to be connected so each flows naturally into the next without jarring the reader out of the narrative. We are always told, “Don’t waste words on empty scenes.” I find this part of the revision process the most difficult. Frankly, I have a million words at my disposal, and wasting them is my best skill.

We are always told, “Don’t waste words on empty scenes.” I find this part of the revision process the most difficult. Frankly, I have a million words at my disposal, and wasting them is my best skill. If you ask a reader what makes a memorable story, they will tell you that the emotions it evoked are why they loved that novel. They were allowed to process the events, given a moment of rest and reflection between the action. Our characters can take a moment to think, but while doing so, they must be transitioning to the next scene.

If you ask a reader what makes a memorable story, they will tell you that the emotions it evoked are why they loved that novel. They were allowed to process the events, given a moment of rest and reflection between the action. Our characters can take a moment to think, but while doing so, they must be transitioning to the next scene. Visual Cues: In my own work, when I come across the word “smile” or other words conveying a facial expression or character’s mood, it sometimes requires a complete re-visualization of the scene. I’m forced to look for a different way to express my intention, which is a necessary but frustrating aspect of the craft.

Visual Cues: In my own work, when I come across the word “smile” or other words conveying a facial expression or character’s mood, it sometimes requires a complete re-visualization of the scene. I’m forced to look for a different way to express my intention, which is a necessary but frustrating aspect of the craft. Code words are the author’s first draft

Code words are the author’s first draft  Thought (Introspection):

Thought (Introspection): That is true of every aspect of a scene—it must reveal something we didn’t know and push the story forward toward something we can’t quite see.

That is true of every aspect of a scene—it must reveal something we didn’t know and push the story forward toward something we can’t quite see.![I, Sailko [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/benozzo_gozzoli_corteo_dei_magi_1_inizio_1459_51.jpg?w=198)

![Sir Galahad, George Frederic Watts [Public domain]](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/220px-sir_galahad_watts.jpg?w=147)